by Amelle Zeroug

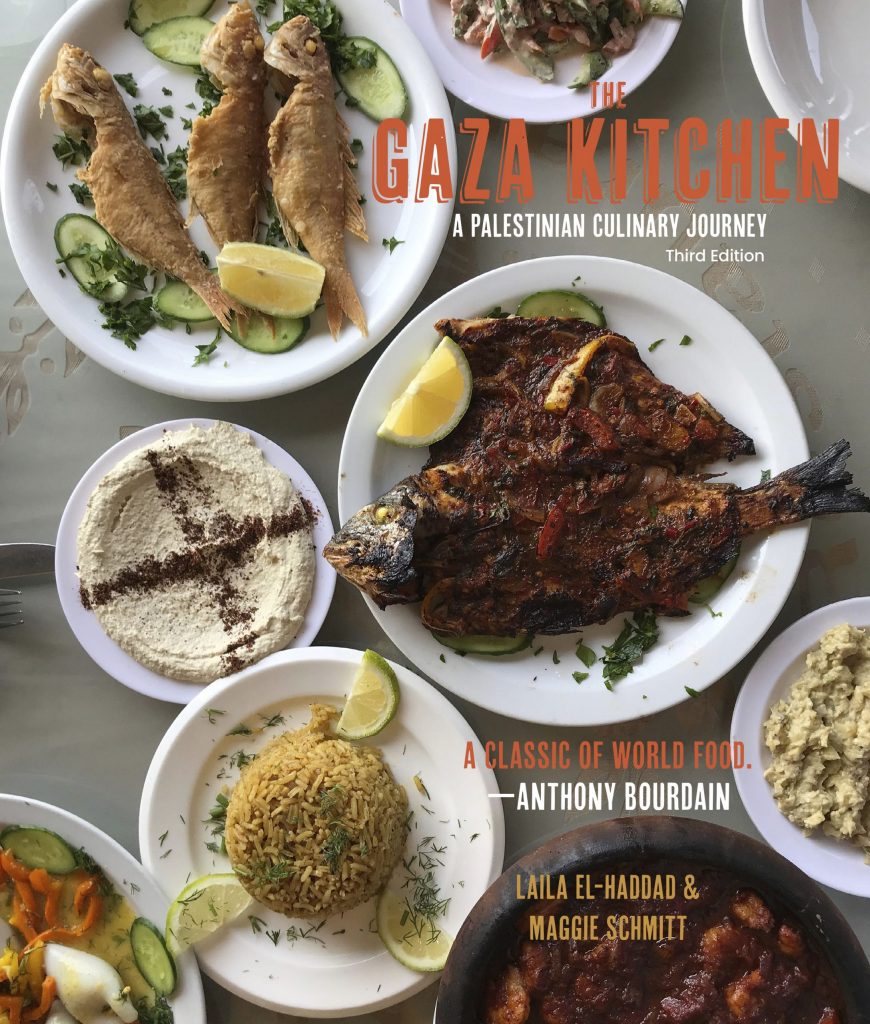

In this moment of new imagining for Palestine, how can we make a plate that brings us together? This was the theme of the expansive discussion via the webinar From Bethlehem to Gaza: Palestinian Culinary Resilience & Liberation, which Just World Educational had the privilege of co-sponsoring in partnership with Middle East Children’s Alliance (MECA), featuring author-activist Laila El-Haddad (The Gaza Kitchen, Gaza Mom & more) and artist-seed librarian Vivien Sansour (founder of the Palestine Heirloom Seed Library). The event was a benefit for MECA’s programs in Gaza and a celebration of the summer release of the Third Edition of The Gaza Kitchen: A Palestinian Culinary Journey by Laila El-Haddad and Maggie Schmitt.

[The video of this 2-hour session of Just World Educational’s Beyond Survival can be viewed via this Resource Page, with many related materials.]

“It’s easier for us to meet in New York or probably on the moon than it is to meet in Gaza now.”

Vivien Sansour

In the first segment of the Beyond Survival series Eating the Other: Toward Food Sovereignty in Palestine and the U.S., Chung-Wha Hong of Grassroots International defined food sovereignty as “the right of peoples to healthy and culturally appropriate food produced through ecologically sound and sustainable methods, and their right to define their food and agriculture systems.” This grounding framework, developed by global social movements, has remained a common thread throughout our Beyond Survival conversations.

The right of peoples to healthy and culturally appropriate food produced through ecologically sound and sustainable methods, and their right to define their food and agriculture systems.

During this virtual summer dinner on August 16th, Laila El-Haddad prepared the Gazan dish Imfasakh Bitinjan with impromptu help from her youngest daughter Bayan. While miles away, Vivien Sansour prepared Mafghosa, a dish from Bethlehem. In this conversation amongst friends, Vivien reminisced about the weekend trips she used to take with her family from Bethlehem to Gaza for shrimp and other coastal delights. Whereas this weekly excursion was possible for Vivien growing up, Laila commented, “It’s easier for us to meet in New York or probably on the moon than it is to meet in Gaza now.” Reflecting on the experience of new generations of Palestinians who have been severed from the coastal cuisine and culture, Laila continued: “it’s so hard to imagine that not long ago this was possible. Your father could make these trips and you could be introduced to different parts of the country and flavors and so on.”

Vivien also highlighted the manner by which the occupation has denied Palestinians the processes, seasons and experiences critical to food production and cultural practices. Travel restrictions, limited water supply, settler backlash, and crackdowns on foraging practices have all served to maim Palestinian food sovereignty and force removal from ancestral lands.

Laila El-Haddad

Laila then illustrated how NGOs and food aid have further changed Palestinian cuisine by failing to provide culturally appropriate or locally sourced ingredients. This impact on the culinary landscape is such that “many of the younger generations really don’t have a recollection of the time when a specific dish was made with olive oil exclusively. This has become the reality. So in that sense, continuing to preserve those dishes also is a way of preserving the history.” On the importance of preserving this cultural knowledge, Laila explained that these dishes “speak of a time that has been forcibly removed from us, from the consciousness of a lot of people. And yet, for those who do remember the elders from the villages, who came as refugees, it is one of the only connections that they have to places that were completely erased from the map and from existence.”

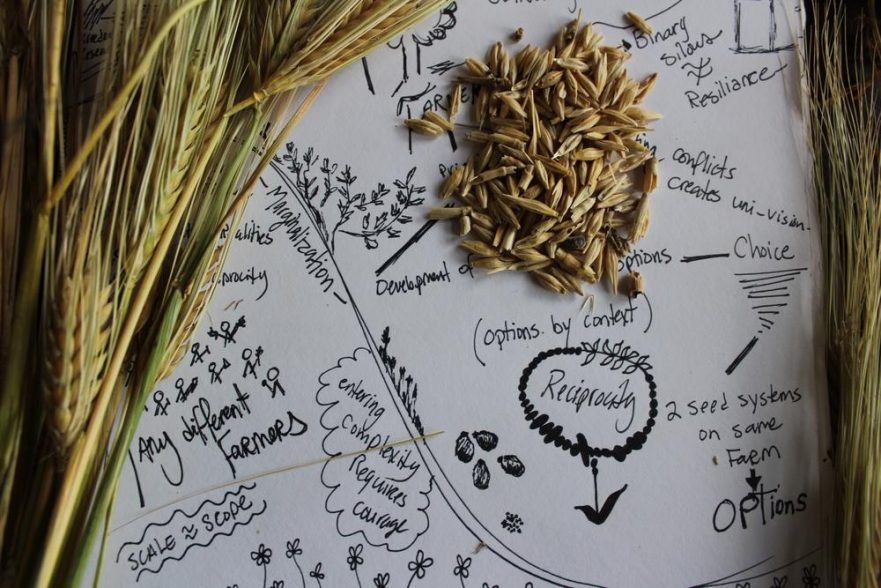

These attempts to limit Palestinian life and dignity and sever connection to land affirm the radically emancipatory work of food sovereignty in Palestine. In describing the live-giving and healing work of the Palestine Heirloom Seed Library, Vivien expressed that seeds and varieties important to Palestinian cultural survival had been lost because of colonial narratives: “we were told that they were primitive, that they were not good enough.” In restoring heirloom varieties to Palestinian farmers and kitchens the library has served to reject colonial standards and celebrate life and revive tradition.

Food and farming in the face of occupation is a place for empowerment, resistance, and joy. Vivien expressed that the Palestine Heirloom Seed Library is a living organization that works not just to preserve and chronicle but rather to rebuild relationships between people and land. On the recovery process of a white cucumber variety thought to have been lost Vivien explained the driving forces behind the project: “Working with farmers to grow this variety again so that it can be available, not just as an idea: can we taste our history? Can we eat it? Can we still have a relationship with it? That’s the living relationship.” On the simple ingenuity of the seed library, Vivien added “It’s not a seed bank with complicated equipment, it was just us as a community saying: we still want to taste that”.

Working with farmers to grow this variety again so that it can be available, not just as an idea. Can we taste our history? Can we eat it? Can we still have a relationship with it? That’s the living relationship.

A sincere devotion to preserving and sharing some of that knowledge is what led Laila on the quest that brought her documentary cookbook The Gaza Kitchen: A Palestinian Culinary Journey to life. As Laila explains, “In the book, you can taste it in the dishes. You can taste these villages that you see nowhere else… I learned all these very specific, seasonal, unique dishes to each village. So in a sense, cooking becomes vital.”

As Laila brought viewers on an intimate tour of her garden in Maryland she showed the wheat planted with her daughters from seeds Vivien had sent her. “They’d never seen wheat grow. I remember as a kid going to my grandfather’s small farm that used to be in an area between Khan Younis and Gaza that was fertile but it was surrounded by Israeli settlements. And in 2005, now it looks like a desert. They just demolished and uprooted everything.” In an important act of generational cultural preservation Laila led her children through the process of making freekeh with the wheat they had grown together. Throughout, Laila drew parallels between the cultivation of a garden and raising children and the spiritual and material preservation of her roots.

“I try as much as I can to grow Palestine in my garden, to build that connection and help the kids understand in a material way, because going back to the idea of access, we don’t have that kind of direct access… Raising children is like cultivating a garden, and you know, starting from the seed and caring for the garden. And it’s very similar in being patient and not always being able to control the forces but removing the weeds, tending to it, it’s true.”

In trying to find her power in the midst of violence and taking care to differentiate between power as dominance and power as in agency, Vivien turned to seeds for solutions: “seeds were a fantastic teacher,” Vivien expanded, “because suddenly I discovered our ancestors were such incredible artists and diligent researchers who worked with nature humbly, as part of it, and developed for us what we have today.” The work of restoring and spreading seed varieties that can withstand increasingly acute climate crises is becoming ever more critical: “Many farmers, even in the western United States, ask me for our Baali seeds, which are seeds that are grown with no irrigation. And that’s because these are seed varieties that were developed by Palestinian farmers from many, many years ago that can withstand thirst.” This process of perpetuating the cycles of sowing, harvesting, teaching and adapting allows us to heed the wisdoms of ancestors who have known and respected these truths long before the dire situation the world is in today.

Seeds were a fantastic teacher, because suddenly I discovered our ancestors were such incredible artists and diligent researchers who worked with nature humbly, as part of it, and developed for us what we have today.”

From Bethlehem to Gaza highlighted the power of storytelling and human connection as resistance to the occupation and its attempts to erase Palestinian life and dignity. As Laila El-Haddad so aptly put it: “we exist and we eat and we love and we live.” Food is a powerful conduit to introduce the issue of Palestine to the broader world without falling prey to reductionist or victimizing narratives. Spanning topics of cultural preservation, health, climate change and generational knowledge, Laila and Vivien explored the central role food sovereignty holds in Palestinian emancipatory efforts.

Please do go and watch all of it – and look at all the other resources on food sovereignty challenges in Palestine and elsewhere that we have produced and gathered on the Just World Ed “Beyond Survival” virtual learning hub.