by Grassroots International

The following report by Grassroots International is crossposted from their website.

Palestinian, Black & Indigenous Struggles for Food Sovereignty

How do Indigenous and Black struggles around food sovereignty in the US intersect with those in Palestine, in terms of both the violence and trauma out of which they emerged and the forms of resistance they have generated? This was the topic of a rich discussion via the webinar Eating the Other: Toward Food Sovereignty in Palestine and the U.S., which Grassroots International had the honor of co-sponsoring in partnership with Just World Educational, featuring author-activists Leila El-Haddad and Maggie Schmitt, chef-activist Brit Reed and farmer-activist Jonathan Wilson.

[The 93-minute video of this conversation can be viewed via this Resource Page, which also contains many related materials.]

Grassroots International’s Chung-Wha Hong opened with an acknowledgement of the timing of the discussion taking place just before the International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People (November 29) and just after the National Day of Mourning (November 26) organized by Indigenous movements in response to Thanksgiving in the US. This was fitting, she said, because “both have to do with violent histories of colonization, racism, expulsion and genocide and, at the same time, vibrant trajectories of resistance.” Playing a central role in these and other struggles, she emphasized, is food:

“From the mass slaughter of buffalo in the US plains region in an attempt to starve the Indigenous peoples who relied on them, to the deprivation of food as a form of punishment and control under slavery, to the ongoing bulldozing of Palestinian olive groves cultivated over generations, there are countless examples of how food has been – and continues to be – used as a tool of oppression.”

On the flip side, she added, “Food has also been central to emancipatory efforts, from the reclaiming of traditional foods and culinary practices, to the preservation of heirloom seeds, to struggles in defense of territory.” Such efforts are encapsulated by the concept of food sovereignty, defined by global social movements as “the right of peoples to healthy and culturally appropriate food produced through ecologically sound and sustainable methods, and their right to define their own food and agriculture systems.”

“You control a nation through its food and resources”

The duality of food as control and food as resistance was picked up by Laila El-Haddad, who powerfully wove together the personal and political as she shared what had brought her into these issues. As a Palestinian born into diaspora, Laila had grappled with a feeling of disconnection from her own history, people and land – a disconnect, she added, intentionally forged over time: “At the heart and root of settler colonialism is control – control over land, resources people – and forcibly disconnecting people from their land and resources.” This is exemplified by the case of Gaza, she explained, where Israel retains control of its borders, sea space, economy, and food supply. Farms on Gaza’s borders have been bulldozed time and time again, while fishermen are shot and detained for crossing lines set by Israel in Gaza’s tightly controlled waters.

In seeking to reconnect to her roots in Palestine, and in Gaza in particular, Laila found food to be a powerful means of doing so, “opening up doors to histories, peoples and lands.” A challenge, however, is that much of the most intimate knowledge on food and foodways has not been recorded, but instead is orally transmitted, and “when the Palestinian nation got scattered, that knowledge went in all sorts of places.”

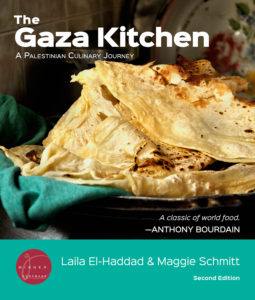

A deep desire to uncover, preserve and share some of that knowledge is what led Laila and her co-author Maggie Schmitt on the exploration that eventually resulted in their book, The Gaza Kitchen: A Palestinian Culinary Journey. As Maggie explains, “The best stories happen in the kitchens.” Kitchens, together with farms, she adds, are sites where meaning is constructed “because of the total materiality and the commitment to perpetuating life that you find in those two places.”

For Indigenous chef Brit Reed, a member of the Choctaw Nation currently living on a Coast Salish reservation in Washington State, the parallels between her own story and Laila’s could not be more apparent. Having been adopted and raised outside of her native land and culture, she too felt both a disconnect from her roots and a yearning to recover them, eventually finding her way back to them through food. Also like Laila, she explained how her personal experience fit into a broader – and also highly intentional – process of alienation. Starting in the 1800s, Indigenous children were sent to boarding schools to rid them of their cultures in order to “kill the Indian and save the man.” Such a practice eventually evolved into widespread trends of adoption of Indigenous children, toward similar ends.

Brit also noted parallels in control over territory and foodways in the Palestinian nation and in Indigenous nations of the Americas. Many of the existing treaties between the US government and tribal nations explicitly include rights to access customary lands and waterways outside of the bounds of reservations, which were historically prisoner of war camps. Nevertheless, acts of hunting, gathering and growing food on these customary lands have repeatedly been criminalized. Much like Gaza, this has especially been the case with the fishing of salmon and other aquatic life considered sacred to tribal communities, with Brit sharing the example of a person who was jailed 50 times in the 1970s for fishing and asserting his people’s right to fish. Such injustices persist into the present, with the Algonquin people’s struggles over sacred moose hunting grounds and the struggles of the Mi’kmaq people over lobster fisheries being two examples of countless others.

Creating spaces of empowerment and healing

For Jonathan Wilson, a multi-racial farmer of Black and Indigenous ancestry who is engaged in various farming projects along the US East Coast, “growing food and reclaiming land is about reclaiming identity that’s been stolen from all of us.” Jonathan’s approach to farming is rooted in abolition, which he sees as inextricable from food sovereignty:

“Food sovereignty looks at how we create autonomy and self-determination against that colonial landscape, that extractive landscape, that we’ve dealt with here on Turtle Island for almost half a millennium. Abolition in farming is rooted in creating spaces where people can choose to heal themselves, where people can choose to empower themselves… It’s a philosophy and practice that we need to embody versus an end road.”

Part of what motivates Johnathan is his personal experience – though he recognizes that this is part of a much greater collective struggle – of “the trauma of trying to farm under capitalism and imperialism and how much we internalize that and how much we actually then put that back out to the universe.” Abolitionist farming, he explains, is challenging that, “challenging the concept that settler colonial practices, whether in Palestine or on Turtle Island, are the foundation that we need to work back from and (acknowledging that) all land is stolen.” It eschews approaches based on reform, focusing instead on getting to the roots of the problems plaguing society. Of course, pushing for transformation within the existing system is rife with contradictions and contradictions, but Johnathan considers grappling with these to be part of the work. He cites as an example the necessity of working with his local department of probation, with all of its problems and contradictions, in order to create transformative experiences for formerly incarcerated youth. The bottom line, as he sees it, is “What does it mean to hold up our community, our people, our comrades? How do you be an abolitionist in spaces where abolition is not welcome?”

The creation of spaces of empowerment and healing under otherwise hostile conditions is a theme that also arose in the research of Maggie and Laila, who recounted their moving visit with a small organic farmer in Gaza, who had created a safe haven on tiny terrain, surrounded by utter devastation, making it “a place of richness and beauty and joy and wealth.” “We saw that same spirit repeated in almost every single household we set foot in, over and over again,” reflected Maggie. Maggie also emphasized that, particularly in the case of kitchens, it is women who are fostering these spaces of resistance in the realm of everyday life, pointing to essential linkages between food sovereignty and feminism:

“If we understand the world from the lens of extractivism and the bodies and lands and lives that it devours, that helps us understand and put in common a lot of these colonized experiences… Feminism – and the feminist economy – kind of turn that logic on its head, asking ‘What would the world look like – how would we organize things – if we put life and the perpetuation of life… at the center?’ And I think food sovereignty is very much about that.”

As the conversation drew to an end, each of the participants reflected on how much resonance they had felt with each other’s stories and insights, pointing to powerful intersections of struggles. They also reflected on lingering questions, such as what does food sovereignty, a concept often linked inextricably with place, mean for people in diaspora, like each of them? To this question, Maggie recalled what Jonathan had shared about abolition being not a destination, but a practice and a methodology to embody. Applying this philosophy to food sovereignty opens up new possibilities for how we think about it – and most critically, how we put it into practice – in each of our respective contexts.