We’re pleased to repost here this essay that our President Helena Cobban recently published on her personal blog, Just World News.

I am already looking forward to the coronation of Charles Windsor, to presumably be held during peak tourist season in 2023? This gives us enough time to do more research into the provenance of the obscenely extensive holdings of the House of Windsor (known until a speedy 1917 name-change as the House of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha)… and to organize a worldwide campaign for the repatriation of so many items in those holdings that were looted and pillaged from around the world during 400 years of English/British imperialism.

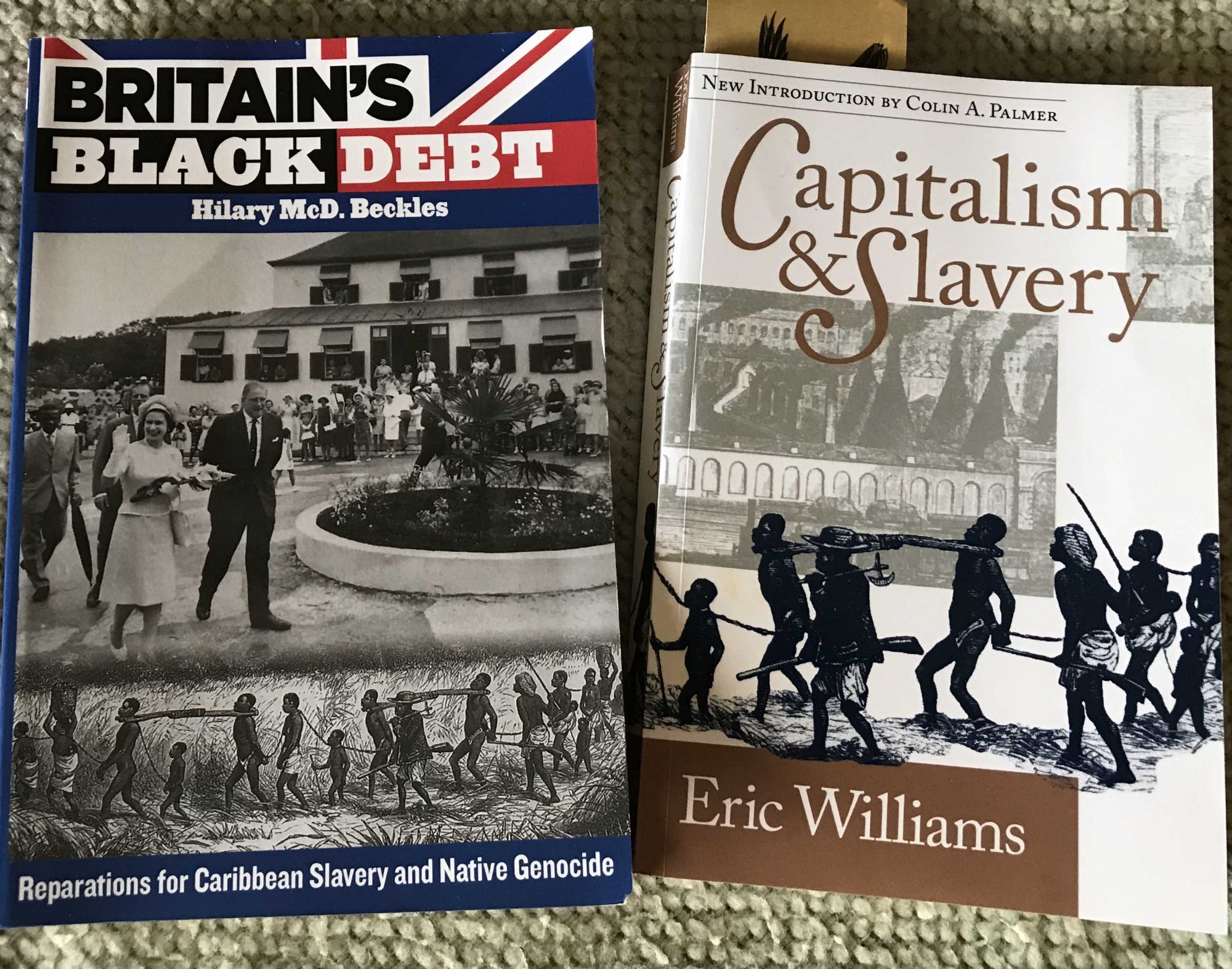

As Eric Williams’s Capitalism and Slavery, and Hilary Beckles’s Britain’s Black Debt tell us, the islands of the Caribbean were the sites of particular kinds of colonial horror: the genocide of the Indigenes and then the shipment into them of hundreds of thousands of enslaved Africans, a large proportion of whom were worked to death in the hyper-profitable sugar plantations that the English (and also French, Spanish, and Danish, etc) ran there.

But it was not only the islands of the Caribbean that were the involuntary sources of English/British wealth! There was also Turtle Island, now known as North America… and massive expanses of land seized in Africa and Asia. These two latter continents were the source of– among other stolen riches–considerable amounts of gold and priceless gemstones, such as we see publicly flaunted whenever the British monarchy puts on a show like the recent funeral parades for Elizabeth Windsor.

When Elizabeth’s mortal remains were paraded through various parts of Britain recently, we got a good look at the Imperial State Crown, the Orb, and Sceptre, which were all placed atop it (as shown above.) That Crown and Scepter each contain large chunks of the famous Cullinan Diamond, which was carved out of the Premier Mine in British-controlled Transvaal, South Africa, in 1905 and was then the largest gem-quality diamond ever excavated. It weighed in at 621 grams (more than 1 lb.)

Recently, we had a sharp reminder that the toxic/destructive legacies of Britain’s extraction of mineral wealth from South Africa still continue. On September 11, a dam holding back sludge from a diamond-sifting operation in the gem-mining South African town of Jagesrfontein gave way, sending waves of sludge that destroyed many workers’ homes.

As that report in the New York Times explained it,

With its first diamonds extracted in 1870 by colonial settlers, the Jagersfontein mine is a relic of a diamond rush that often exploited Black South Africans while enriching white owners. It yielded a 650-carat diamond, among the world’s largest, that was acquired by British merchants and from which was cut the jubilee diamond, named in honor of Queen Victoria’s diamond jubilee.

Throughout the whole of today’s South Africa, the legacies of British colonial rule are still evident: In the massive hills of mine-tailings that surround the whole of Johannesburg; in the clear disparities in water availability that you see if you fly over the frontiers of the former “Black Homelands”; in the horrendous inequalities that remain between the country’s “White” and non-White populations, which were never addressed at all during the process of formal political democratization…

But back to the Cullinan Diamond… In 1907, the colony’s legislative council voted to donate that diamond to British King Edward VII. In London, the prime minister thought that was a bad idea, but his Colonial Under-Secretary, Winston Churchill, persuaded the king to accept it anyway, to be “preserved among the historic jewels which form the heirlooms of the Crown”. The big diamond was cut into a number of smaller pieces that were then polished.

By the time that was done, it was King George V’s wife, Queen Mary, who got to wear the biggest two polished chunks, known as Cullinan I and II. When she died in 1953, she left all the pieces of the Cullinan Diamond that she’d been using to Elizabeth Windsor. Along the way, arrangements were made for Cullinan I to be fitted (removably) into the Sovereign’s Sceptre and Cullinan II to be fitted (also, I think, removably) into the Imperial State Crown…

So a queen could, whenever she wanted, simply unscrew the clunkers from the formal regalia and wear them round her neck!

We can expect to see all these fine pieces of imperial booty being paraded and displayed again when Charles get crowned.

Technically, when a British monarch is crowned inside Westminster Abbey, they use an even heavier piece of headgear to do that: St. Edward’s Crown, which weighs 4.9 lb., and can never be taken out of Westminster Abbey. The “Imperial State Crown”, that we saw placed on Elizabeth’s coffin, is only 2.3 lb., and is the one the monarch wears for all other events apart from the coronation.

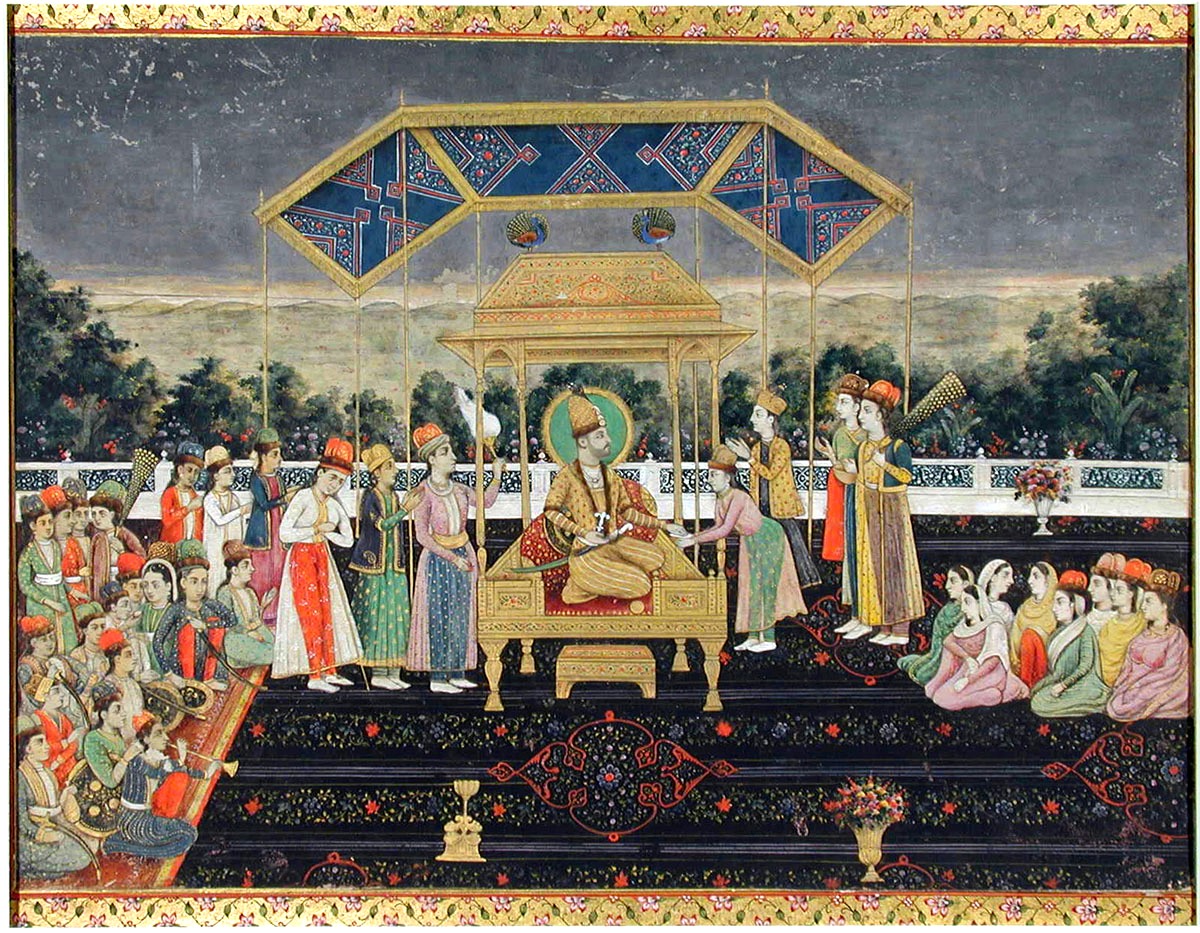

… And let us not forget the Koh-i-Noor Diamond, one of the largest cut diamonds in history, which was one of many gems that embellished the Peacock Throne built by India’s Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan in the early 17th century CE. At the end of a fairly colorful history at the hands of various Indian rulers, the Koh-i-Noor ended up being held by the Sikh Kingdom of Punjab.

In 1849, Britain’s military vanquished that kingdom in the Second Anglo-Sikh War, and the Punjabis were forced to cede the diamond to Britain’s Queen Victoria. (They also had to cede control of the whole of their kingdom to the London-based, quasi-governmental East India Company.)

Later, the Koh-i-Noor Diamond was recut and incorporated into what became known as the Queen Mother’s Crown.

Immediately after India won its independence from British rule in 1947, it demanded the return of the Koh-i-Noor. But so too did Pakistan, which seceded violently from India during the independence process, and Afghanistan.

For the past 75 years the British Government has rejected all those claims, insisting that the Koh-i-Noor’s status is “non-negotiable.”

It is clearly ways past time to repatriate all these grisly reminders of empire as part of a broader reparations effort. How many new houses, roads, and bridges might be built in flood-ravaged Pakistan from the sale or repatriation of just a few of these gems?