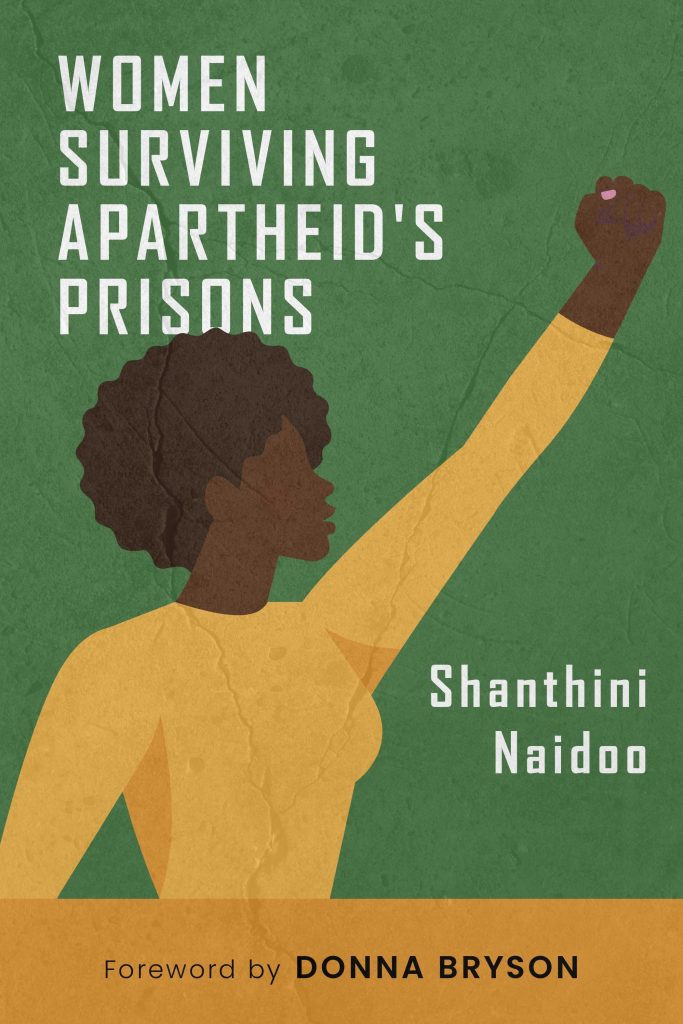

On February 1, Just World Ed was honored to work with Just World Books to present an online launch for Women Surviving Apartheid’s Prisons, a book by Shanthini Naidoo that profiles four women who played a key role in South Africa’s struggle against apartheid back in the 1960s. These four, along with Winnie Mandela and two other women, were among the 22 grassroots organizers for the African National Congress (ANC) imprisoned by the apartheid regime and subjected to various tortures including lengthy periods of solitary confinement in an attempt to “break” them and force them to testify against each other.

None of the indictees in that historic “Trial of 22” broke under the pressure. The authorities had to abandon their hope of a show trial; but the torture and imprisonment left longstanding scars on all those thus brutalized. For Ms. Mandela and the other four women featured in the book those scars were compounded by the fact that, on being jailed, they were torn away from their children and families.

Ms. Naidoo’s book was first published (under the title Women In Solitary) in South Africa, last year. It was one of the first to shine a spotlight on the suffering that the apartheid regime’s brutality inflicted on women freedom fighters.

The book’s launch in the United States was a very special event. Being organized online, it was possible to bring into a single digital “gathering place” not only Ms. Naidoo (with us from Johannesburg) but also, from Washington DC, South Africa’s ambassador to the United States, Hon. Nomaindiya Cathleen Mfeketo and Just World Ed’s President Helena Cobban, and from Denver, CO the journalist and author Donna Bryson, who contributed a powerful Foreword to the U.S. version of the book.

You can view the whole 65-miunute video of this event here.

During the “Q&A” session, this group was also joined by Shanthie Naidoo, who is one of the women featured in Women Surviving (and no relation to the author.) Shanthie Naidoo and her spouse Dominic Tweedie joined the event from Johannesburg.

It had many very stirring moments. In introductory remarks, Amb. Mfeketo thanked Shanthini Naidoo for having produced the book, noting,

Yes, we are talking about seven women, including our icon Winnie Mandela, but there were hundreds, thousands of people who died for this freedom, who suffered for this freedom, but you hardly get anything written about what happened to them… We’re standing on the shoulders of those people who pave this way for the freedom we enjoy today.

Ms. Bryson then led a conversation with Shanthini Naidoo and about the book, in which Amb. Mfeketo also joined.

Ms. Naidoo recalled that she had first heard about these four sheroes from the 1960s when she went to Winnie Mandela’s funeral in 2018:

I was writing for the Sunday Times in South Africa about her time in solitary confinement in prison. She’d spend 491 days in prison. And we’d known a little bit about this, but I hadn’t realized that there were six other women who were part of that trial. Two had passed on and the other four was still alive and still in Johannesburg. And in fact they’d attended her funeral, but very quietly and very, you know, without any fuss or any recognition. So I looked for them and got to know them a little bit in terms of writing those articles at the time of Winnie Mandela’s death and realized that this was a whole story to tell: there were four life stories that could be shared very similarly to Winnie Mandela’s.

Ms. Bryson steered the conversation briefly to a comparison of the state of democracy in the United States and in South Africa. Ms. Naidoo remarked that she thought South Africa’s democracy was still flawed: “And part of the flaw is that we don’t know our history as well as we should. And therefore we don’t recognize each other yet.”

Amb. Mfeketo joined in, offering a strong plaudit to the equality movement that she had seen (from a diplomatically and medically appropriate distance), on the streets of the United States in summer 2020: “You’ll appreciate, I was only here from March and the bulk of what I saw was the Black Lives Matter, which in my view was much more than we would do in South Africa. I’m saying much more because I saw a group of everybody in America– Black, Brown, and white, young, and old– standing up for a good cause.”

Ms. Naidoo then shared an excerpt from Women Surviving. This one was from the chapter about Ma Rita Ndzanga, who was detained along with her husband Lawrence Ndzanga in 1969, when she was in her thirties. On that occasion she, like Ms. Mandela, was held for 491 days. (In 1976, the couple, who had five children, were detained again. During that detention, Lawrence Ndzanga died under questioning.)

The excerpt Ms. Naidoo read touched on the question of the lengthy after-effects the first imprisonment had had on Ma Rita Ndzanga:

She still lives in the house she shared with Lawrence on Koma Road, Senoane, Soweto. ‘In the country, right now, we never lived like the way we are living now,’ she tells me. ‘We have got lives, really. We wanted our dignity back.’ She dismisses any consideration of psychological help. ‘I didn’t have any counseling. I only went to a doctor when I felt pain or if I didn’t have tablets. I still take tablets.’ She gestures to her forearm. ‘If you see my arm when I fell [during the 1969 interrogations], I could feel the pain from here. Sometimes I can hardly pick my hand up. It’s painful. Nowadays, I am tired. People think we don’t want to associate anymore, but it is because of these sicknesses. All that, it comes from detention without trial.’

There followed more discussion among the panelists about the kinds of traumas that can linger after imprisonment. Amb. Mfeketo made her own deeply moving contribution. She had been a grassroots, pro-ANC organizer during a slightly later period than the women profiled in the book and she revealed that she had twice been imprisoned by the apartheid regime.

She noted that soon after South Africa’s first democratic election in 1994, the country had established a Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), which specifically invited survivors of the harms inflicted by apartheid to come and testify:

Part of establishing that [the TRC] was to deal with the trauma of what happened over a long period of apartheid. I must say there are people who went to testify about that trauma, and those who were responsible for that were called to the TRC as well. And it was on the basis of not only hearing the story of people, but also being able to see if the perpetrators of that must be arrested or must be forgiven because we are reconciling and you know, that those people were affected also saying, I forgive you.

But I must say lots of people didn’t attend: the trauma was so overwhelming. They couldn’t. I couldn’t go because I wasn’t sure what would happen after you go to the TRC and open your soul, what’s going to happen after that,

The panelists then considered the matter of why stories of courage under duress like the ones told in Women Surviving have not been more widely known in the post-apartheid era– in South Africa itself, or anywhere else. One of the explanations Amb. Mfeketo gave was that in the post-apartheid era, the people who had formerly been stalwart anti-apartheid activists and leaders, acting under extreme duress, suddenly found themselves having to run the country: “I think we were sort of overwhelmed by this new era. And… most people were put in different places you know, to prepare for the new South Africa more than telling your story.”

Shanthini Naidoo added a couple of other explanations:

I also think that this humility and discipline in the generation that fought in the apartheid struggle… It was very selfless. It was not as vocal and as visible as activism is now…

Also, it was illegal for them to write anything down and keep records of the work!

She said she hoped that when people read Women Surviving Apartheid’s Prisons they would be able to identify with the women’s bravery and to learn more about the sacrifices they had made.

The panelists also discussed why women, in particular, seem so reluctant to tell their stories. Amb. Mfeketo alluded to some of these difficulties when she noted that when she had recently produced a short videotaped recounting of some of her memories of her time in the struggle that Ms. Cobban had asked her to produce for Just World Ed:

I didn’t even include the periods I was detained, both in the State of Emergency and under Section 29. And when I lost a 16 year old son, then, the way those security branches, you know, just told me point-blank that I killed my son by being such an irresponsible woman, staying for almost a year in prison without my children– when I knew they had something do with that accident and the killing of my son.

So I think it’s how we’ve been trained that, you know, you don’t get arrested to come back and write a story about that… But I’m hoping at least, the new generation, and as people read these books, eh, we will get into that culture of of writing about even no matter how small something is, writing about it in order to educate other people.

Ms. Naidoo urged the ambassador to write down her memories, even if just starting in small pieces. She added, “It’s also important to recognize and realize when you been a part of something as big as the apartheid struggle– which was many years, many decades long– to realize that those different parts are very important.”

She summed up the tenor of the book thus:

These stories will make you cry and make you think and make you reflect. But they are also wonderful stories to tell which are part of it and love and and life. You know, Joyce Sikakhane-Rankin’s story is an absolute, wonderful love story as well, about how she was put in prison because she was engaged to someone she wasn’t allowed to be. And in Women Surviving, you will read the story about how eventually, you know, fate changed that narrative for her. It’s a very interesting part of the book.

So, you know, there’s, there’s a lot to tell and and some of it is really hopeful and really brave and, and exciting and interesting. So, you know, it doesn’t make for, for solemn reading, all of it, which I’m very glad to say.

After the conversation among Ms. Shanthini Naidoo, Ms. Bryson, and the Ambassador there was a rich “Q&A” section involving Americans and South Africans. It included a delightful appearance by book profilee Ms. Shanthie Naidoo and her spouse Dominic Tweedie, sitting side by side in Johannesburg. (Mr. Tweedie’s anti-apartheid activism and organizing in London back in the 1970s had first connected him with Shanthie Naidoo after she went into exile there, and they’ve been married for many years.)

Mr. Tweedie noted that recording the memories of former organizers and leaders in the struggle was very difficult: “We’ve been trying for many years. For, for us, for the Naidoo family, for Shanthie and the people mentioned in the books, I think that Shanthini has been a godsend to us really, I must say. It’s not like everybody would do this!”

He concurred with the reasons Shanthini Naidoo and the ambassador had offered about why stories like those told in the book were not previously recorded, and added another of his own:

There’s another factor, I believe, which is that life is very competitive… within politics, within the liberation movement. It’s competitive and people are jealous. People would feel that they were boasting, that they were trying to use leverage their own life for, for advantage. They would be made to feel that, and then they’re talking about things that are very tender and sensitive and personal… Then you would withdraw from doing that… And I can see this all the time.

I believe some people are… shamelessly boastful, and sometimes artificially and wrongly so. Let’s just say, there are a lot of white people who take credit for the liberation of South Africa. You may not believe that, but in fact, they believe that they did it! De Klerk is the first one. He believes that he liberated South Africa. He’s proud of his Nobel prize. He thinks it was down to him, you know, incredible, really.

So this is a competitive thing. If you go into it, you’re going to have to battle it out as well. And you’re going to be facing people who may want to ridicule you and shame you and all sorts of things. This is why it doesn’t come out easily. So Shanthini has done us a hell of a good service, something really special. I want to thank her for that!

Shanthie Naidoo added her thanks to his. Shanthini Naidoo immediately replied, “Dominic and Auntie Shanthie, please don’t thank me! It’s their story to tell!”

Other questions came in from Dr. Gwendolyn Zoharah Simmons, a veteran Black American activist and organizer in both the civil-rights movement and the anti-apartheid movement, and Just World Ed board member Dr. Alice Rothchild.

Dr. Rothchild’s question was about the relationship between feminism and the anti-apartheid struggle and the roles women took on in the struggle. It provoked a fascinating discussion. Shanthini Naidoo said, “I think feminism was something the woman in the story in particular completely espoused.” Recalling that their activism had been in the 1960s , she said:

They had multiple barriers to work through… So can you imagine when women were not wearing trousers and you had these brave journalists and you know activists who are meeting in dark corners without fear of being arrested, or maybe they did have some fear, but they did it anyway.

Ms. Bryson said,

As I was reading your book, I so often thought of this, the idea of ‘women’s work,’ and that… a lot of the things that these women did that was heroic was just considered what women should do and they shouldn’t talk about it. And then also this idea that…when the ambassador talks about having to get busy, building a new South Africa after liberation, there just wasn’t time for this kind of reflection. And I think women did most of the work there too. There just wasn’t time. There’s so much women’s work!

For her part, Amb. Mfeketo recalled that the time when women in the movement had felt themselves to be the strongest was the period between the ‘seventies and the time in 1990 when the political organizations were unbanned and when their leaders– who had lived in exile in many different countries during the banning– started to come back to the country. During those years, people like her who were pro-ANC and supporters of a broad range of other anti-apartheid parties and organizations had worked together in a semi-illegal civilian mass organizing movement called the United Democratic Front (UDF.)

She recalled that during that period, women had felt themselves strong,

precisely because some of the organizations, women organizations that were there and fought and fought really hard, where women were, said from the beginning– and this is where the feminist idea also was nurtured– women were saying: we will take our decisions ourselves. We will not rely on men to take decisions for us. And I must say it worked. Many things that we went through at that time, we went through as women. We didn’t wait for men, whether they are in an organization or not to guide us on what to do.

She said that after the leaders and members of the big political organizations returned from exile after 1990, there were some attempts to keep the same kind of focus on women’s self-organizing and women’s concerns that existed during the UDF period, but they seemed to fade over time.

Too soon, the online gathering came to an end. But we’re delighted that, by presenting the archived video on our Online Resource Center on Women in South Africa’s Struggle Against Apartheid, we can make this richly moving and informative discussion available to interested researchers and learners for many years to come.