We’re delighted to crosspost this transcript of a talk that our board member Alice Rothchild gave recently, in Brookline MA. This is crossposted from the Brookline Chronicle.

by Alice Rothchild

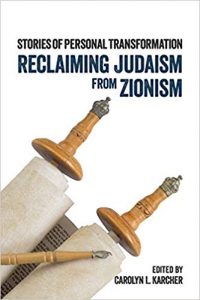

Today I’m going to be discussing the recently published book, Reclaiming Judaism from Zionism: Stories of Personal Transformation. The book is a collection of curated essays by rabbis, students, academics, and activists, and includes my chapter titled: Choosing a different path. I am going to start with some definitions that I have gleaned from my own personal research and also from the excellent introduction written by Professor Carolyn Karcher who is the editor of this book.

I would define Judaism as a religion, centered on tikkun olam, on pursuing justice and loving the stranger. It is a body of sacred texts, rituals, and ethical precepts. This is very different from the definition of a Jewish macher (see Yiddish – big shot) in Boston who once said in answer to the question: “Can you be a Jew and not be a Zionist?” “You don’t understand, Israel is the religion.” Clearly I take issue with that.

Zionism, on the other hand, is a political ideology of Jewish nationalism, a belief that Israel is necessary as a safe haven after the Nazi Holocaust, that nothing but a Jewish state can protect Jews against anti-Semitism and the next holocaust. For many Jews, Zionism is the core of Jewish identity and the litmus test for being “in the tent.” I also think of Zionism as a response to the lack of progress in the emancipation of Jewish communities and the rise in anti-Semitism in Europe in the 20th century.

So let’s start with a bit of history. Political Zionism is a recent phenomenon. This is very different from my zayde’s messianic Zionism which was more a belief that the Messiah would come someday and everything would get better, but don’t hold your breath. This was often followed by a fatalistic shrug and more davening.

In the US in 1878, Christian Zionism exploded with the bestseller by William Blackstone titled Jesus is Coming. Justice Brandeis called Blackstone “the father of Zionism.” The first US Christian Zionist lobby effort occurred in 1891 where the assembled advocated for the creation of Jewish state in Palestine so that Jews could escape the pogroms and Christians could prepare for the rapture.

In Europe in the 1800s, the Jews of Central and Western Europe did not live in ghettos. They were emancipated after the French Revolution which started in 1789. They defined their identities as Austrian, German, French, etc. and regarded Judaism as a religion not a nationality. This was different for Russian Jews who lived in isolated shtetls and saw themselves as a people, a national minority, an ethnic group.

In the 1880s, Russian Jews began fleeing pograms and anti-Semitism and were encouraged to taking refuge in the biblical homeland, so by 1903 we see the First Aliyah to Palestine. Most Russian Jews, however, fled into Europe and the US and they were met with hostility and anti-Semitism, not of the Christ-killer variety, but a pseudo-genetic, anthropological, biological jargon that was used to justify group aggressiveness and the demonization of the other. As you know, this flourished in US and was used to justify slavery and the dispossession of Native Americans. It was all part of the highly popular eugenics movement. So, anti-Semites labeled Jews as a race and Jews accepted that classification and claimed they belonged to an “imaginary ‘Jewish race.’”

A primary figure in this movement was Theodor Herzl, a secular Viennese Jew who is said to have had a Christmas tree and an uncircumsized son. The Dreyfus case (1894-1906) in France, where a German Jewish officer was convicted of treason and then exonerated in a second trial, triggered anti-Semitic riots all over France. Herzl witnessed this and the election of anti-Semites in the Austrian government and became disillusioned. He decided the only solution to anti-Semitism was a Jewish nation and published a Zionist manifesto in 1896. A year later he organized the First World Zionist Congress in Basel, Switzerland stating that the presence of Jews in a country produces persecution and assimilation is impossible. This was the birth of modern Jewish Zionism.

In keeping with the times, these folks modeled the Jewish state on European colonialism. They envisioned a society of Jews under some kind of European protectorate that would negotiate possession of a “neutral” piece of land which would bring prosperity and modernity to the natives. They ultimately decided on Palestine as the most attractive to the Jewish masses, a potential “villa in the jungle.” Thus we see the merging of Zionism and Jewish nationalism with Great Power imperialism. This set the stage for the conflict between Jewish versus Palestinian (Christian and Muslim) nationalism.

From 1904-1914 the Second Aliyah occurred, Jewish settlers made up 5% of Palestine, and began developing institutions and infrastructure for a Jewish state which included plans to transfer the native population to neighboring Arab lands.

At the same time in Britain, the fundamentalist Christian, Lord Balfour, believed in transferring Jews to Palestine in order to hasten the second coming of Christ. During WW1, Ottoman Turkey sided with Germany (against British imperialism) and lost its Middle Eastern empire to Britain and France. So we see the merging of British imperial interests with Zionist goals. Britain got the League of Nation mandate to govern Palestine and Balfour lobbied the US for approval for a British protectorate in Palestine that would be a national Jewish home. In the US, one of the most prominent supporters was again, Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis. This led to the Balfour Declaration which declared that Britain supports a national home for Jews in Palestine as long as there is no prejudice against existing non Jewish communities. (italics mine)

Now it is important to remember that this all was very controversial in Jewish and British circles. People argued that a separate homeland would segregate Jews, that this reversed the ongoing emancipation and was anti-democratic, Jews were not a nationality, and anti-Semitism was not eternal.

It is interesting to note that the Bund (a forerunner of Workers Circle) was anti-Zionist, but mainly focused on workers’ rights and socialism. They viewed Judaism as a secular national identity. In the US, reform Jews believed that Judaism was a spiritual religion. They claimed that the US was their country, Zionism was inherently a political movement, and worried about the accusation of dual loyalty which had plagued Jews in the past.

Nonetheless, liberal Zionists promoted the idea that Jews could be liberal at home, but ignore the plight of Palestinians “over there.” They believed that Jews and subsequently Israel were creating an ideal democratic society and dismissed the dual loyalty issue. They said that Jews were Jewish Americans, analogous to Italian or Irish Americans with a home country they supported. But imbedded in this belief system was an imperial mindset, a belief in manifest destiny. Zionist settlers were the pioneers and Arabs were the Indians. We were witnessing “a triumph of white civilization over savagery.”

In the 1930s, the rise of Nazism persuaded people that anti-Semitism was forever and that Jews needed a Jewish State to be safe. I think it is very important to analyze the language that was developing during these times. Political Zionists described diasporic Jews as subhuman; they used anti- Semitic tropes. Just think of the difference between the scruffy little Yid and the proud glorious Hebrew.

One of the most egregious examples of this attitude is seen in the language of Vladimir Jabotinski, the founder of Revisionist Zionism which was the forerunner of today’s Likud Party. At first he felt warmly towards Mussolini, the German Reich, and actively supported fascism.

Our starting point is to take the typical Yid of today and to imagine his diametrical opposite … Because the Yid is ugly, sickly, and lacks decorum, we shall endow the ideal image of the Hebrew with masculine beauty. The Yid is trodden upon and easily frightened and, therefore, the Hebrew ought to be proud and independent. The Yid is despised by all and, therefore, the Hebrew ought to charm all. The Yid has accepted submission and, therefore, the Hebrew ought to learn how to command. The Yid wants to conceal his identity from strangers and, therefore, the Hebrew should look the world straight in the eye and declare: “I am a Hebrew!”

For me, the fact that Zionism embraced the idea that this pathetic, scoliotic, weakling, diasporic Jew (who was often to be blamed for anti-Semitism) needed to be Aryanized into the bronzed, muscular, Hebrew farmer/warrior tilling the soil in the Galilee is a chilling realization. We can see that the early Zionists adopted some of the language of anti-Semites who increasingly defined Jews as a highly deficient race in need of a major cure – working and defending the land of Palestine.

I would argue that the evolution of Jews as a people who lived by Torah and its commandments into a biological race with distinct characteristics, (the money Jew, the ghetto Jew, the swarthy, hook-nosed Jew) mirrors the worst canards of anti-Semites, European fascists, and white supremacists. This is a very troubling origin story.

It should then not come as a surprise that the founder of modern Zionism, Theodore Herzl, and subsequent fathers, looked at anti-Semites as “‘friends and allies’ of his movement.” Zionists and anti-Semites shared a common goal: One group wanted all the Jews to emigrate to Palestine to establish an ethnically pure Jewish nation state and the other group wanted to get rid of all their Jewish countrymen. Emigration was indeed a splendid and final solution to the eternal Jewish problem.

Most people are also unaware that in 1937, Adolf Eichmann, along with his supervisor in the Nazi party’s intelligence agency, traveled to Mandate Palestine, disguised as a German journalist, to investigate the feasibility of German Jewish deportation to the region and to evaluate the functions of the Zionist organizations within Palestine. Eichmann also secretly met with Feivel Polkes, a representative of the Haganah, (which became the Israeli Defense Forces), to discuss this plan. It is important to remember that Eichmann’s interest was in deporting Jews as efficiently as possible, not in supporting the development of a strong Jewish state that might threaten the economic fortunes of Nazi Germany.

There is another interesting factoid: the transfer “Ha’avara” Agreement which ultimately resulted in the rescue of 20,000 Jews. Nazi Germany agreed to compensate those German Jews who left for Palestine after the liquidation of their property by exporting German goods of equal value to the country. The emigrants then received some of the proceeds from the sale of the goods. This led to an end of the boycott of Germany and a financial boost for their economy which was still mired in WW1 reparations and the Great Depression. As Leon Rosselson wrote:

Between 1933 and 1939, 60 percent of all capital invested in Jewish Palestine came from German Jewish money through the Transfer Agreement. Thus, Nazism was a boon to Zionism throughout the 1930s.

In 1935, the German Zionist branch was the only political force that supported the Nazi Nuremberg Laws in the country, and was the only party still allowed to publish its own newspaper the Rundschau until after Kristallnacht in 1938.

Clearly, in 1939 the Final Solution changed everything.

After WW2, despite all the fears and controversy, the UN partition plan led to the creation of a Jewish state. After the founding of the State of Israel in 1948, Albert Einstein wrote a letter to the New York Times regarding the visit to the US by Menachem Begin, a leader of the Irgun, head of the right wing nationalist Herut Party (which morphed into Likud), and later the sixth Israeli prime minister:

Among the most disturbing political phenomena of our time is the emergence in the newly created state of Israel of the ‘Freedom Party’ (Tnuat HaHerut), a political party closely akin in its organization, methods, political philosophy and social appeal to the Nazi and Fascist parties….They have preached an admixture of ultranationalism, religious mysticism and racial superiority… it is imperative that the truth about Mr Begin and his movement be made known in this country.

All very troubling.

Now after the 1967 war, we see the rise of Fundamentalist Christian Zionism in the US with their generous support of Israeli settlements, and their belief that the Jewish state and the ’67 war were God’s will and the fulfillment of biblical prophecy. Liberal Protestants and Catholics embraced Christian Zionism as a form of repentance from Holocaust guilt. This all led to the growing belief that any criticism of Israel was inherently anti-Semitic.

I believe that the birth and growth of Zionism needs to be understood in all of its aspirations and contradictions.

In this book, Reclaiming Judaism from Zionism, Rabbi Brant Rosen, discusses a non-Zionist Judaism. He writes of Diasporism that after the destruction of the temple, Judaism became a religious system, a spiritual response to dispersion and exile, a worldwide spiritual peoplehood, multinational, multicultural. Power stemmed from religious belief not military might. He notes that Israel invests in global militarism because it is a state, not because it is Jewish. The militancy of the state counters that sense of permanent Jewish victimhood which is part of our cultural inheritance. He writes that much of Jewish culture and religious practice developed outside of national sovereignty. This is the focus for many younger, religious Jews today.

So how did all this play out in my life?

I would like to share a selection of readings from my essay in Reclaiming Judaism from Zionism:

Looking at my life’s trajectory, I have often wondered how I, a middle class daughter of striving, first generation Jewish parents, started to challenge many of the foundations of my upbringing. Clearly coming of age in the 1960’s with American counter culture as the wind in my sails and the Vietnam War as my own personal experience of US foreign policy, created space to think independently. Discovering feminism and attending medical school at a time when women were a small minority, professors routinely referred to their elderly patients as “girls,” and members of my nascent consciousness-raising group were gripping our plastic speculums and talking about redefining our relationships with men, gave me a lot to think about.

In terms of my Jewishness, I started my life in a very traditional American place. Faced with the activism of my youth, Israel’s increasingly belligerent occupation of the West Bank, Gaza, and East Jerusalem, multiple hard-to-defend wars, and a growing awareness of “cross sectional” issues around racism, police brutality, militarism, and US foreign policy, I was gradually forced to re-examine much that my family once held dear and to face the consequences of my actions. As an increasingly secular person, I also began to scrutinize the meaning of my Jewishness; the uncomfortable consequences of Zionism and my personal responsibilities in a world rife with contradiction, fear, and conflict. So how did all that happen and where am I now?

… My parents grew up a few blocks from each other, met at night school at Brooklyn College (Rosner sat next to Rothchild), and were both rebels in their outward rejection of speaking Yiddish as our mamaloshen and maintaining an Orthodox kosher home, and in their eagerness to embrace a modern American life with mowed lawns, a love of Mahler, and occasional goyishe friends. My mother read Women’s Day, a guide to being a good housewife, and along with chicken and challah on Shabbos, made orange jello molds with grated carrots layered at the top, a distinctly post-war dessert, the bland happy taste of the ’50s. At the same time, my parents managed to let me know that we were different, that we were from a distinct and endangered tribe. I marvel at that inherited sense of being at odds with American culture and society, of feeling so Jewish in a non-Jewish world despite rising economics and acceptability. I learned early that I was an outsider in the dominant American culture, that stories keep our history and culture alive and also create the learned truths about that history. I have also come to understand in my own journey, that people survive by telling their stories and that the victors in history most often create the prevailing and accepted narratives.

And I was deeply enmeshed in that Jewish story; there was my unlikely love of gefilte fish and my real talent for making matzoh balls, as well as the level of guilt and responsibility I felt for the world’s disasters. In sixth grade each student was asked to draw a picture of what he or she really wanted. I do not recall what my fellow classmates yearned for, but I do recall that my desire for “World Peace” was considered to be moderately peculiar. In college I met upper- class, private school girls who wanted to touch me, gushing, “I’ve never met a Jew before.”

… As a teenager, I was lulled into the liberalism of Adlai Stevenson and John F. Kennedy, but I discovered there were harsh limits. When I came home with an African-American boyfriend, my modern, liberal, pro-civil rights, tolerant mother warned me that if I married a non-Jew, then “Hitler’s dream would come true.” She begged me to understand what I would lose, never considering what he also might lose should he marry me. She cried and threatened to sit shiva, mourning my “death,” banishing me from the family forever. This was a powerful message to a budding 19-year-old exploring her own identities and passions; the threat of permanent expulsion from the enfolding arms of my childhood. In a painful and tumultuous evening, my mother morphed from ally to threat and I saw excommunication as a real possibility. Little did I know what lay ahead.

This is quite a heritage, a potent mix of trauma, memory, tribalism, and assimilation. As a family, we prided ourselves on our differentness and our ability to survive against the odds of anti-Semitism, pogroms, near annihilation, and the sweatshops and poverty of the Lower East Side of New York City. At the same time that we were thriving in multicultural, upwardly mobile suburbia, I knew in a strange, unconscious way, like Jews everywhere, that we were potentially all victims, we were in some way all survivors, and the world was an unforgiving place; the threat of another Holocaust lurked behind every international crisis, every unkind word.

… In the mid 1990s, fortified with a growing understanding of colonialism, racism, immigration, and Islamophobia, and increasingly disenchanted with the version of Israeli history I had learned in Hebrew school, I began an active search for the stories that I had missed. I began to listen to dissenting Israeli Jews, Palestinians, and other Arabs in the Boston area. I began to make invisible people visible to me, to confront the trauma and fear that I had inherited, and to hear and feel our enormous human commonalities; the common language of denial, despair, endurance, and recovery. I started to realize that the “troubles” in Israel did not start in 1967 with the Six Day War and the occupation of East Jerusalem, the Golan, West Bank and Gaza. I began to recognize the importance of revisiting the events of 1948, the year I was born and the State of Israel was founded; to hold both the story of my own people and the stories of the people who were killed, dispossessed, and displaced partly as a consequence of my own people’s tragedy, in my head and in my heart simultaneously.

… Early on I saw myself as a student of the conflict, bearing witness to the realities that I observed on the ground, working with dissenting Israelis and Palestinians.

…I worked with US activists and members of the Israeli left who were focused on civil, human, and political rights for Palestinians in Israel and the occupied territories as the fundamental basis for a viable, secure Israeli state. I watched the “left” in post-Oslo Israel shrink to desperately small numbers, and I observed Palestinian civil society coalescing around a commitment to nonviolent resistance to oppression. I began to understand as the Jewish settlements exploded in the West Bank and East Jerusalem with increasingly restrictive bypass roads, checkpoints, permits, and the snaking separation wall, and as the Israeli government declared the Jordan Valley a closed military zone, that the government of Israel (like all governments) was not going to give up power voluntarily. I watched with growing horror at the racist, right-wing swing of successive Israeli governments and the unleashed bigotry and aggression of Jewish settlers towards their Palestinian neighbors. It became increasingly clear to me that the expulsion, dispossession, and war against the indigenous Palestinians that started long before 1948 was actually continuing unabated, disguised in the language of the endless, stillborn “peace process,” Jewish exceptionalism, water, security, and the racist demonization of Palestinians. This growing understanding led me to fully embrace the international call for boycott, divestment, and sanctions against Israel as the most creative, powerful, nonviolent work that I could support.

[I’m now going to reflect on some of my experiences as an activist, speaking out on these topics. I trained and was on the staff for years at Beth Israel Hospital in Boston…]

… Other faculty gave talks on their various medical missions and experiences around the world–I wanted my time as well. In an earlier discussion with my department chief about visiting colleagues in Israel, he (an ardent Zionist who led delegations to Israel, especially focused on their emergency medicine and response to terrorist attacks), had said to me, “You are a danger to the Jewish people.” (Who knew?) Needless to say, my efforts to give a departmental presentation were unsuccessful until five years later when he left the department. I applied to the new acting chief, was accepted, and when my impending grand rounds was announced, the department received 100 emails protesting my appearance. I was asked to remove the word “occupation” from the title, (ultimately the presentation was titled: “Healthcare in the West Bank and Gaza: Examining the impact of war on a civilian population, a personal journey”), and warned to stay away from politics.

… At a John Carroll University political science class in Ohio, “Peacemaking in the Palestine Israel Conflict,” there were complaints from the local Hillel stating that Jewish students did not “feel safe” having me on campus and a major faculty meeting was held to discuss my upcoming event. Fortunately, the professor was supported by the university administration. Nonetheless, 100 students packed the class, including many from Hillel. The Hillel contingent was mostly silent during my talk, although some approached me individually afterwards. The most disturbing interaction was with the Israeli shalicha, (ambassador, hired by Jewish institutions to represent Israel and to shape the conversation about Israel in temples, Hillels, community groups, etc.). She aggressively attacked me as a “liar,” chastised me for “doing a great disservice,” and refused to “agree to disagree.” Loud bullying seemed to be her main strategy and the students watched closely.

… As expected, temples are the most challenging venue for me. This is where I feel I am up against the wide spread“McCarthyism” in the mainstream Jewish community. At a reform temple in Ithaca, NY, I found that when announcements were placed in the temple newsletter, if the speaker was left-leaning on Israel/Palestine, there was a disclaimer that stated that the speaker does not represent the temple community, thus setting the normative opinion. In a Bethesda, Maryland Reconstructionist synagogue, Erez Israel class, I noted that all the maps for the course and in the temple labeled “Israel” were actually the one state “Greater Israel.” When one of the older men took issue with my comment “the victors write history,” he said “We are not the victors, we lost six million times.” I could feel this sense that many in the class could not move beyond living in the Holocaust, living with a permanent victimhood as well as a lack of understanding and sympathy for “Arabs,” thus the dominant narrative became a blinder to seeing a co-victim’s reality. In an orthodox synagogue in the DC area, my film screening for a men’s club, which was organized by an orthodox human rights lawyer and Hebrew school teacher, was summarily cancelled by the rabbi.

Moving out into the Jewish community, the Sacramento, California, Jewish Federation newspaper, The Jewish Voice, refused to post an announcement for my film, as they deemed it an “anti-Israel event”. A few years earlier they had refused to announce my book reading, also claiming it was “anti-Israel.” In a vibrant Jewish community at the Beachwood Library in Ohio, I encountered a very conflicted audience, many unaware of the millions of dollars being spent on Israeli hasbara, the very aggressive control of “Israel messaging,” and the intense muzzling in the Jewish community and on campuses. One woman noted that we can have this kind of open conversation “anywhere in the US” but in Arab countries we would be censored, arrested, “sold into sex slavery.” I pointed out that actually I cannot have this conversation in most temples, Hillels, and Jewish community centers and that rabbis routinely cancel my appearances. She pointed out that the poster for my talk earlier in the day was offensive: it had the word “CONFLICT” in large letters and a picture of the separation wall, so “it says what side you are on.” I pointed out to her that, problematically, there is an actual conflict and the separation wall is an issue and an important symbol of the occupation. There was clearly a low bar for feeling threatened. The most disturbing moment for me came at the end when an older woman walked up to the women selling my books, and announced these “should be burned.” A gentleman behind her retorted, “That’s what they did in Nazi Germany.”

… At World Fellowship, a progressive family summer retreat in New Hampshire, a woman in the audience told me of her child attending a public school in New York City where they were studying indigenous peoples and as an example the teacher stated that the Jews were the indigenous people in Israel and they were being treated badly by the Palestinians. Her daughter piped up that she thought it was really the other way around. The girl was sent out of class to the principal’s office, her parents were called, and there was a stern warning about such talk. When the mother agreed with her daughter, the principal explained that that version of history was not allowed in New York City public schools.

… As an activist, I now relate to many communities: the more mainstream Jewish organizations look at me as the classic “self-hating Jew” because I value Palestinian life and aspirations as much as Jewish life and aspirations. Also because I see the increasing right-wing, racist policies of the State of Israel backed by the US as the fulcrum where real change must come, and this involves challenging the basic assumptions of political Zionism and Jewish privilege and majority rule. The activist Jewish communities and younger Jews welcome my insights and join me in a call for democratic values and respect for international law, with the acknowledgement that Palestinians are now the oppressed people in this international equation, (along with Mizrachi Jews and African asylum seekers, but that is another story).

The good liberal Jews in the middle who are holding on to the idea that Israel can be Jewish and democratic and are not yet willing to face the deep contradictions within Zionist society, continue to squirm and support the human and civil rights movements within the US and Israel, calling for an end to the Israeli occupation without facing what I see as the core issue: Jewish privilege and its consequences.

Christian groups and particularly African-Americans, increasingly welcome “a Jew we can talk to.” as many find themselves aggressively challenged by their Jewish friends and rabbis when they raise the kinds of serious and contradictory concerns outlined here.

Muslim friends are relieved to find a Jew post 9/11 who embraces people not as stereotypes, but as fellow human beings with complicated and often traumatic life stories trying to move forward in a world that is so violently Islamophobic.

I believe that resolution of this conflict is central to the resolution of many of the tragedies that have engulfed the Middle East. I would urge us to start with ourselves. I have come to understand that it is critical to separate Judaism the religion from Zionism the national political movement; “Zionism has hijacked Judaism.” I would advocate defining a Jew as someone grounded in religion or culture and history, a set of ethics, a sense of peoplehood; all definitions equally compelling.

While Jewish Israelis have long looked down upon the Diaspora as not “real Jews” with “no right to criticize, because you don’t live here,” Diaspora Jews are reclaiming our legitimacy and our voice as Jews. We are delineating the racist ideology of anti-Semitism from thoughtful moral criticism of the policies of the country, Israel. Thus the treatment of and solidarity with Palestinians has now become the civil rights issue of the day for modern younger Jews who will be here long after the older post-Holocaust generation has moved on and no longer shapes the boundaries of intelligent discourse and definitions of normalcy. Mostly what I see is that Diaspora Jews are starting to own the Nakba, [the Palestinian experience of 1948, literally the Catastrophe], as part of our story. I believe that after centuries of powerlessness, how we as a community handle our new position of power and privilege is critical to the survival of an ethical Jewish tradition as well as a just resolution to a more than century-old struggle in historic Palestine that is being fought in our name.

Thank you.