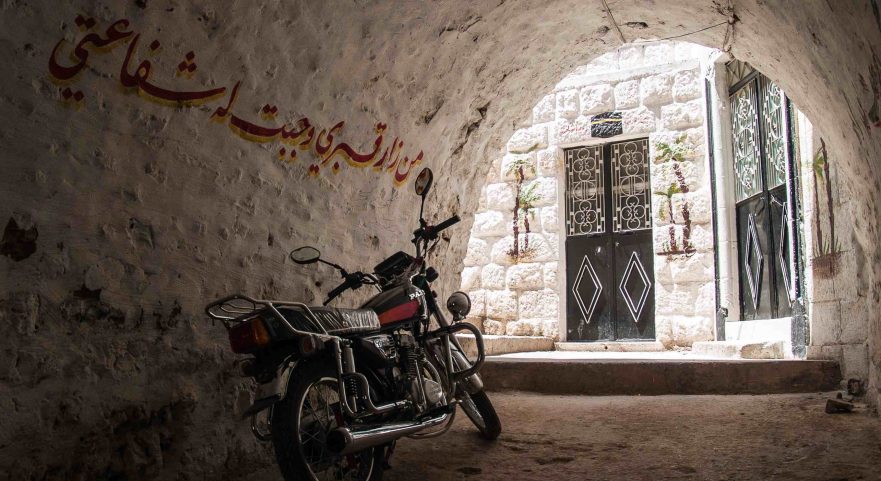

We are pleased to publish the following essay by Daniel Demeter, whose book Lens on Syria: A Photographic Tour of Its Ancient and Modern Culture was published by Just World Books in 2016. His earlier post about Bosra can be found here. (The image above is one of his photos from the Idlib-area town of Jisr al-Shaghur.)

by Daniel Demeter

Until recent years, Syria’s Idlib governorate was largely unknown even to most individuals familiar with the Middle East—let alone to Western policymakers and political commentators. The mostly rural province had several towns of moderate size, but the provincial capital (which was bypassed by the major highways linking nearby Aleppo to Lattakia and Damascus) hosted a small population of only around 100,000 residents. With an agriculture-based economy and underdeveloped infrastructure, the small province in the country’s northwest was considered something of a backwater.

Now, Idlib is the focus of fierce political debate and international media coverage.

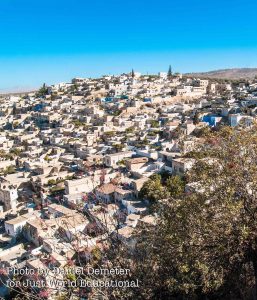

Over the years I spent living and traveling throughout Syria, 2003-2009, I came to know Idlib intimately. The primary reason: Idlib province hosts perhaps the densest concentration of standing Byzantine-era archaeological remains anywhere in the world. Exploring and photographing these sites (of which hundreds survive, collectively known as the “dead cities”) became one of my passions—and took me throughout the province’s towns, villages, and countryside. The photographs in this blog post were all taken in Idlib province, in those years.

While I would use public transportation to get as close to these archaeological sites as I could, much of my exploration was conducted on foot. During these travels, I was regularly, and graciously, invited into people’s homes and businesses; I was given rides in their cars and on their motorbikes; and I often joined them to drink tea, or eat meals. Through these experiences, I learned a great deal about the local history, culture, demographics, and beliefs.

Idlib is—or was—a very diverse province. Most of Syria’s religious minority groups had a presence there: Druze, adherents of various denominations of Christianity, and Shia and Alawite Muslims. The Druze community was centered on a cluster of mountain villages not far from the Turkish border. The largest of these, Qalb Lozeh, features a remarkable Byzantine-era basilica church. North of Jisr al-Shaghur was a series of predominantly Christian towns and villages, centered on the charming town of al-Quniyeh with its cobblestone streets. Predominantly Alawite farming villages were found in the mountain foothills at the western edge of the province, while two predominantly Shia villages—two of only four in the country—were located on the outskirts of the provincial capital.

The province’s diversity extended into the political views of its residents. Many in Idlib espoused secular nationalism, a perspective of shared Syrian cultural identity that has long been promoted by the Syrian state. But on occasion I was also confronted with intolerant and sectarian attitudes, typically directed against Idlib’s religious minorities. This was a time of intense sectarian violence in neighboring Iraq, and these conversations left me deeply concerned about what might transpire if similar instability and collapse of state authority were to take place in Syria.

As the conflict in Syria unfolded, my worst fears became realized. The situation in Idlib became particularly dire in 2015, when a network of anti-government groups, strongly dominated by Islamist extremists, managed to seize control of most of the province.

The Druze population of Qalb Lozeh and surrounding villages were forced to convert to Sunni Islam under threat of death. When some residents resisted, extremist militants massacred two dozen of them, and destroyed local religious shrines and tombs. The Christian community that resided in the northwestern villages of al-Quniyeh, al-Yaqoubiyeh, and al-Jdeideh was largely displaced, their churches shuttered and crosses removed. The Alawite villagers in the west of the province fled for their lives, while the Shiite villages of Kafraya and al-Fuaa were put under a tight, and often deadly, rebel siege for two and a half years. (After suffering hundreds of casualties inflicted by mortar attacks and suicide bombings, a negotiated settlement granted them passage out of the province in July 2018.)

Violent acts against minority communities have not been the only crimes committed by the armed groups ruling the province. The town of Jisr al-Shaghur, with its attractive Ottoman-era architecture and famous Roman bridge, was settled by thousands of Chinese Uyghur militants and their families, and their Turkistan Islamic Party militia has terrorized the local population. Foreign fighters with extremist ideologies dominate many other militias in the province, too. Infighting between these groups has been common, and have included IEDs, car bombings, assassinations, and firefights—with civilians too often caught in the crossfire. In recent weeks Idlib residents advocating negotiations and reconciliation with the government have been threatened with public execution.

The province’s rich cultural heritage has also faced grave threats. Under the rebels, illicit excavations and looting of archaeological sites became commonplace. Priceless historical artifacts have been trafficked to Turkey’s black market in antiquities. The more ideologically extreme militants have even engaged in destruction of historic tombs and shrines. Among the monuments targeted were those celebrating al-Maari, a famous 10th century Arab philosopher, author, and poet who was heavily critical of religion, in his hometown of Maarat al-Naaman.

Idlib is now the focus of international media coverage, as the Syrian government and its allies appear poised to launch a large-scale military offensive to restore central government authority to the province. Humanitarian concerns regarding this campaign (as well as the actions of rebel forces) are quite legitimate, but the Western corporate media’s narrative has been extremely one-sided. The voices that dominate the discussion continue to be supporters of regime change in Damascus—and of the use of Western military intervention to achieve that.

It has become routine for regime change advocates to feign outrage over humanitarian concerns, in order to provoke Western military intervention in Syria. The same arguments were earlier made during Syrian government advances in Homs, Wadi Barada, Aleppo, al-Ghouta, Daraa, and several other regions. But after the government successfully restored its authority in those places through a combination of negotiations and military pressure, the worst-case scenarios that were presented as near certainties never materialized.

In late 2016, Western supporters of regime change were in near hysteria over the government’s campaign to recapture the enclave in Eastern Aleppo that the rebels had previously held. Their claim that 300,000 civilians were living in that enclave—an estimate that they maintained until the final weeks of the battle—proved to be hugely exaggerated. The vast majority of the civilians who did remain there found safe passage to the government-held side of the city. The predicted massacres never materialized, and the besieged and retreating rebels were even granted safe passage out of the city. Since then, over 400,000 displaced Syrian civilians have returned to Aleppo according to United Nations estimates, and the city’s residents have celebrated its return to normalcy.

Then, earlier this year, the Syrian government launched a campaign to recapture the southwestern provinces of Daraa and al-Quneitra. Once again, pro-interventionist voices dominated Western media coverage, using manipulative cries of an impending humanitarian crisis in an attempt to prompt American military intervention. Thankfully, they failed to achieve their desired outcome. Within the two provinces themselves, the vast majority of opposition militants worked out reconciliation agreements with the government. Widespread fighting, destruction, and loss of life were avoided.

The interventionists’ approach towards Idlib has been nearly identical. They have exaggerated the population of the province beyond reasonable estimates—claiming over three million civilians reside there. The prewar population of Idlib was barely 1.5 million, and the number of civilians displaced from the province over the course of the conflict likely exceeds the number of civilians that have relocated there during it. Idlib is often deceptively referred to as “besieged”, but it has a lengthy frontier with neighboring Turkey and is also connected to rebel-held territories in the neighboring Aleppo province. The frontier with Turkey continues to provide a source of supplies and weaponry for opposition militants.

For many of those expressing exaggerated fears of humanitarian disaster in Idlib or other areas of Syria being retaken by the government side, American military intervention is presented as a solution to the problem. Yet no explanation of how U.S. or NATO military action might benefit the Syrian people is ever presented. The precedents from Libya, Iraq, and Afghanistan are not at all encouraging.

(These same voices do not express similar humanitarian concerns when the United States engages in military offensives in the region. The U.S. campaign against Islamic State in the northeast Syria inflicted enormous damage across the Syrian provinces of Aleppo, al-Raqqa, Deir al-Zur, and al-Hasakeh—a broad region that was home to several million civilians. In neighboring Iraq, the Nineveh offensive placed a civilian population of over three million under threat. The Syrian city of al-Raqqa and the Iraqi city of Mosul remain in ruin as a result of these offensives—mostly as a consequence of American airstrikes. The double standard is evident.)

Desperate warmongers continue to look for any excuse to promote American military intervention in Syria—and concealing their intentions under the guise of humanitarianism is the strategy they persistently cling to. But airstrikes and missile attacks against Damascus would only have the consequence of inflicting additional suffering upon the Syrian people, over 75% of whom now live in the areas under government control. Such strikes would destabilize regions of the country that have returned to normalcy, exposing more civilians to violence and lawlessness, and would extend a conflict that has already dragged on for far too long.

Reconciliation agreements, like those implemented in the Daraa province a few months ago, remain the best option for bringing an end to the terrible suffering that the war in Syria has inflicted over the past seven years.

View across the Byzantine-era town of Serjilla (4th-6th century CE). Visible are a church, a meeting hall, and several large villas.

Those repeatedly advocating for American military intervention against Damascus are motivated much less by genuine humanitarian concerns, than by geopolitical ambitions. Syria remaining mired in conflict, weak, divided, and with its economy on the verge of collapse, is not detrimental to their objectives. On the contrary, it is their preferred outcome should regime change not be achieved. Syria has been the target of U.S. sanctions continuously for the past 39 years, a thorn in the side of American-Israeli hegemony in the region.

That is why the foreign backers of opposition militants view reconciliation agreements with the government as a threat. They have no interest in seeing Syria reunified under a central government, as that reduces their influence in the conflict. Rather than encourage opposition militants to engage in negotiations with Damascus in hopes of ending the conflict nonviolently, they seek to maintain leverage against the Syrian government to further their own interests.

In Daraa province, the threat of a Syrian government offensive brought about numerous negotiated reconciliation agreements and resulted in a mostly peaceful conclusion. There is little reason to believe that the outcome in Idlib would be much different, once that pressure is applied.

While many civilians in Idlib hold anti-government sentiments, and some opposition fighters in the province have legitimate grievances with Damascus, few are interested in dying for a lost cause. Like in Daraa, reconciliation will be possible once extremists can no longer hold these populations hostage. The local population has suffered greatly under the repression and brutality of these militants, which include in their ranks tens of thousands of foreign extremists. The civilian population of Idlib would strongly prefer to avoid violent battles resulting in the destruction of their towns.

Westerners genuinely concerned about the welfare of Syria’s people should root for the success of negotiated reconciliation agreements in Idlib. They should be skeptical of the many well-funded propaganda campaigns designed to demonize the government in Damascus and build support for regime change there. The persistent threat of Western military strikes only abets the extremist militants controlling Idlib, encouraging them to provoke such intervention while rejecting negotiations entirely. Supporting parties that seek to end the conflict through dialogue—and marginalizing the extremist militants who oppose it—is the best solution to the ongoing violence in Idlib. The sooner that is achieved, the sooner Idlib’s people (and the people of the rest of Syria) can get back to rebuilding communities town apart by this terrible war.