On June 19, the government of Israel reduced the supply of electricity it sends to the two million Palestinian residents of the occupied Gaza Strip to a level that allows them only three to four hours of power per day. The Gaza Strip is a highly urbanized, densely populated area, heavily dependent on electricity for basic necessities of life such as:

- refrigeration of foods in hot summer weather;

- sewage and waste-water treatment;

- light for children, youth, and others to study by in the evenings;

- necessary hospital and other medical services, and so on.

The Israeli government claimed that its decision was taken in response to a decision the Ramallah-based “Palestinian Interim Self-Governing Authority” (PA) took to reduce its payments for fuel sent to Gaza. The two million residents of Gaza thus once again became pawns in the attempt those two parties were making to persuade them to renounce or overthrow the Hamas-led governing authority that they– along with the people of the occupied West Bank– duly elected to power, back in the elections of January 2006.

The Palestinian Human Rights Organizations Council, a coalition of some ten human-rights civil-society groups active in Gaza and the West Bank, denounced Israel’s latest measure. PHROC called upon the international community

“to immediately and effectively act to prevent the reduction in electricity provided to Gaza from Israel, the occupying power, and to ensure the restoration of the power plant in Gaza… and to respect and ensure respect for international law, including that Israel fulfills its duties as occupying power towards the protected Palestinian population.”

Israel, of course, denies that it is still the “occupying power” in Gaza– though no other government in the world agrees with them on that. (If it were not the occupying power, then it would have no standing to exercise the tight degree of control it has maintained over all of Gaza’s land and sea borders continuously for the past 50 years and which continues until today…)

As an occupying power, under the 4th Geneva Convention of 1949 it has a basic responsibility to protect the safety and wellbeing of the residents of the area occupied.

Israel’s policy of tightening the screw on Gaza via its control of the power supply comes in the wake of countless other Israeli aggressions against Gaza, notably the numerous military assaults it has launched against Gaza over the past 70 years, including the extremely destructive assault of summer 2014 which claimed more than 2,000 Palestinian lives during 51 days of fighting.

Ever since 1948, Gaza has occupied a very special place both in the history of Palestinian nationalism and in the history of Israeli war-planning.

As Israeli historian Ilan Pappe and others have carefully established, in the Jewish-Arab fighting that erupted in Palestine immediately after the UN’s November 1947 adoption of a “Partition Plan for Palestine”, the Jewish-settler militias in Palestine pursued a plan to seize and hold control of as much of the land of historic Palestine as possible– including considerable areas that had not even been allotted to the “Jewish state” in the Partition Plan.

One key goal of these militias was to clear these areas as much as possible of their indigenous Palestinian Arab inhabitants.

In 1947-48, the Arab community in Palestine was far less well-organized and less well-armed than the Jewish settler (minority) community there. By that point, the Arabs had been the subject of brutal repression by Palestine’s British rulers for more than two decades. On May 15, 1948, the Jewish leaders in Palestine declared the establishment of the State of Israel, and the leading Jewish militias became transformed in that moment into the army of that state. The Palestinian Arabs never achieved either a state or an army, and the armies from neighboring Arab states that came into Palestine after May 15, 1948 to “help” them did not achieve very much either– except that the (British-led) Jordanian Army seized and kept control of the West Bank area and the (British-supported) Egyptian Army seized and kept control of an area around Gaza City, which became known as the Gaza Strip.

The Israeli state retained control of a portion of Palestine considerably larger than the area the UN had allotted it in 1947 and it continued until the end of 1948 to expel as many of the Palestinian residents of that area as it could. The Palestinian expellees fled in all directions (except into the desert of Sinai.) More than 100,000 of them ended up in the Gaza Strip, giving it the highest proportion of refugees to non-refugees of any of the areas that hosted the Palestinian refugees.

Today, some 70-plus percent of the population of the Gaza Strip are refugees from 1948 or their descendants. In the West Bank, the proportion is far lower– more like 25%– while in the neighboring countries of Lebanon and Syria the proportion is lower yet. (Jordan is a special case: It, too, like Gaza, received a large influx of Palestinian refugees in 1948; and it received another influx in 1967. But for many decades after 1948 many or most of those refugees were given Jordanian citizenship– while they still did not renounce their claims to homes and properties they had been expelled from in what became Israel.)

In Gaza, as in Lebanon and Syria, the refugees remained stateless. This made them all extremely vulnerable to the whims of the governments under whose control they came.

The high concentration of Palestinian refugees in Gaza has always made Gaza a crucial incubator of Palestinian nationalism. Yasser Arafat and the tight-knit group of his colleagues who founded the basically secular Palestinian nationalist movement Fateh– which later came to dominate the Palestine Liberation Organization, PLO– were nearly all young men who lived through the immediate post-1948 years in Gaza. Later, several of them fanned out to the rapidly developing states of the Gulf, which were sorely in need of men of their level of education.

No surprise, though, that the central organizing tool of Fateh throughout all its early years was a demand for the “Return” of all the refugees.

Much later, in late 1987, when the Islamic Resistance Movement (Hamas) was established, its founders, too, included a heavy predominance of people from Gaza.

Gaza has truly, since 1948, been the most important incubator of the mass-based Palestinian political movements. Perhaps that accounts for some of the particular anger that successive Israeli governments have directed toward Gaza– though the extremely aggressive actions that Israeli governments have undertaken against Gaza have (to put it very mildly) done absolutely nothing to endear Israelis to Gaza’s residents.

Ever since 1948, Gaza’s history has thus been tightly tied to the question of refugee rights, as could only be expected given the high– and over time slowly increasing– proportion of Gaza’s people who are refugees.

What constitutes a Palestinian refugee, and who is responsible for them?

Given that 69 years have now passed since the Nakba (catastrophe) that befell the Palestinians when the State of Israel was established, both these questions are harder to answer than you might first imagine.

A first stab at the answer of what constitutes a Palestinian refugee would be that it is anyone who was an inhabitant of Palestine who fled their home or were expelled from it during the fighting of 1947-48 and was not then allowed to return to it.

In all conflicts, people flee from their homes when the fighting comes too close. That doesn’t mean they lose their rights to those homes and properties. Indeed, the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights states that everyone has the right to leave the land of their birth– or to return to it. And in practice, in all the complex conflicts the world has seen over the past 60 years, one of the main strands upon which a durable peace has been built is the peaceable return of refugees from those conflicts to their original homes– or if those no longer exist, at least to their home communities.

Another key fact here: The status of being a refugee passes down from parent to child. A child born in a refugee camp has the same civil status as their parents. In the case of Palestine’s refugee population of 69-years-and-counting, their communities have seen three or even four generations grow up as refugees. The claims they have on their ancestral homes and properties have not disappeared.

In the case of Palestine’s refugees, in December 1948, the U.N. General Assembly adopted Resolution 194 which states that,

the refugees wishing to return to their homes and live at peace with their neighbors should be permitted to do so at the earliest practical date, and that compensation should be paid for the property of those choosing not to return and for loss of or damage to property which… should be made good by the Governments or authorities responsible.

So, pending the return of the Palestinian refugees to their ancestral homes, who is responsible for them?

During the first year of their dispossession/expulsion, the arrangements made for their care were very impromptu. (The authorities in the hosting communities, like most of the refugees themselves, imagined that the fighting would soon be over and the refugees could return to their homes.)

In most cases, the local towns and cities where they ended up, or the national governments, made some provision for them. In Gaza, the numbers of refugees overwhelmed the local authorities, and the Egyptian Army had no way of looking after them. There, amazingly enough, it was the American Friends Service Committee (Quakers) that looked after the refugees for the whole first ten months of their arrival. The Quakers used skills they had acquired looking after refugees in Europe, 1945-47, to organize rudimentary refugee camps with sanitation, feeding, basic health services, and even some schooling.

But soon enough, the Quakers (in Gaza) and the local/national governments in Lebanon, Syria, and Jordan all realized two things: (a) Israel was not going to let the refugees return to their homes any time soon, and (b) the challenge of looking after these large numbers of refugees was huge. So the United Nations stepped in. In 1949 it established an agency called United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA), and that agency has borne the basic responsibility for the survival and where possible the wellbeing of Palestinian refugees ever since.

Notable fact: The UN’s “big” refugee agency, the UN High Commission for Refugees, was not established until a year after UNRWA; and UNRWA was never folded into it. So the number of refugees under UNRWA’s care is not counted in the number of refugees that UNHCR periodically says it is looking after. If someone cites a figure for the number of refugees in the world, check to see if it includes the Palestinian refugees.

In 2016, there were 5.27 million Palestinian refugees registered with UNRWA.

This page on UNRWA’s very informative website gives you some good basic information about UNRWA’s work in Gaza.

Another notable fact: The 5.27 million “registered” Palestinian refugees counted by UNRWA are far from being all the Palestinian refugees there are around the world, all of whom are covered by Resolution 194 and who therefore at some (so far only theoretical) level have a right to return to their ancestral properties inside “1948 Israel”. That’s because UNRWA has always been just a humanitarian-aid body, not a political body that in any sense at all claims to “represent” the refugee Palestinians at a political level. (If there is such a body around today, that would be the PLO, though its claim to “represent” all the Palestinians around the world has become very thin over the past two decades… )

But back to why UNRWA’s count of “registered” refugees does not cover all the Palestinian refugees. Back when it was doing its early planning in late 1949 and 1950, UNRWA obviously needed to develop a count of the number of people for whom it needed to find shelter, food, clothing, etc. So it said it would register people only in the four areas of Lebanon, Syria, Jordan (which then included the West Bank), and Gaza– and that those it registered had to be in demonstrable need of its services.

At that point, there were numerous Palestinians in those four areas who were scraping by on their own or with the help of relatives, or who were relatively well-off, but who anyway did not want or need to go and register with UNRWA or who were too far away from UNRWA’s registration offices to go there and register. There were also needy and non-needy Palestinians in several other countries (such as Iraq), where UNRWA wasn’t offering any services at all.

But it counted then, and continues to count today, only those in the areas it serves who are those whom it counted back in 1950 and their descendants, and who are still needy.

This relates, too, to another crucial fact about the population of Gaza: Because of the policy of deliberate economic strangulation that Israel has pursued toward Gaza’s people for the past 50 years and especially the past 15 years (in complete violation of the Fourth Geneva Convention), the whole Gaza economy is basically on life support; and over the past 50 years probably a majority of the people who would otherwise still be in Gaza if it had a normally thriving economy have been driven to seek a basically decent life elsewhere.

Every family now in Gaza has at least a third of its family members now living elsewhere. And the draconian limits Israel has placed on the movement of people in and out of Gaza mean that all the people in Gaza suffer from separation from very close relatives. Grandmothers can’t touch and hold their grandkids; sisters are separated from brothers; sons from their fathers; and so on.

… Well, that’s some basic background on the issues of refugees and resistance in relation to Gaza. Now, here are some other great resources if you want to learn more:

1. The website “Gaza in Context” is centered around a 20-minute film giving background about Gaza, that was released in summer 2016. The GIC website also provides a very well documented PDF of its script, a teacher’s guide, and a great, 110-item bibliography that is mainly (but not solely) of resources about Gaza. Some of the infographics and other visuals on the film are very powerful.

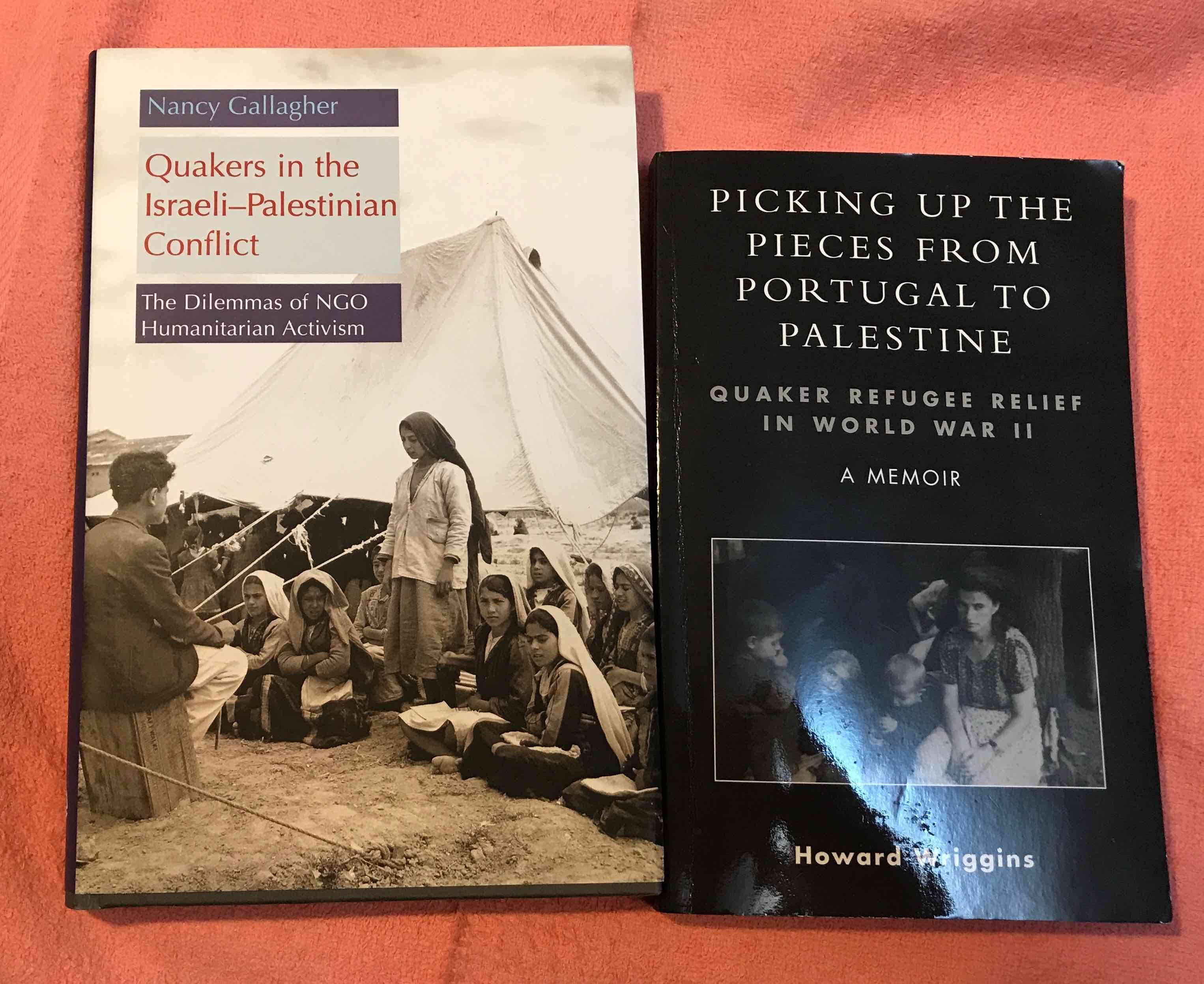

2. Two great books about the early Quaker relief efforts in Gaza. Nancy Gallagher‘s (on the left) is very thorough as she mined AFSC’s archives on the mission in Gaza. One thing Quakers then, as today, agonized over was whether their humanitarian-aid efforts merely ended up consolidating a de-facto situation of Israeli ethnic cleansing and domination. Howard Wriggins’s memoir is his firsthand account.