by Richard Falk

We are delighted to crosspost this piece from Global Justice in the 21st Century, the blog of JWE Board Member Richard Falk.

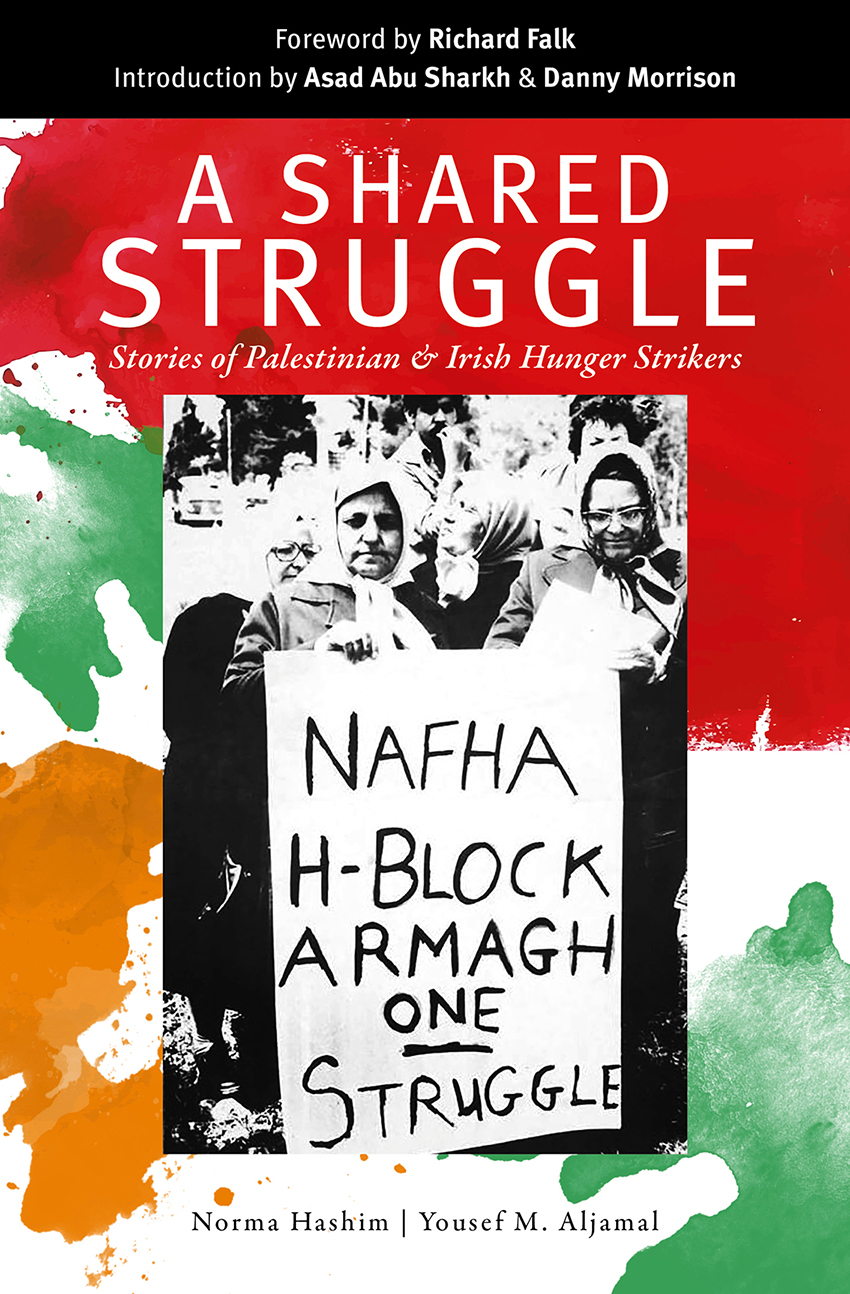

The following is the foreword to a collection of essays relating the comparative experience of Palestinian and Irish hunger strikers. A Shared Struggle: Stories of Palestinian and Irish Hunger Strikers was expertly edited by Norma Hashim and Yousef Aljamal.

Desperate circumstances give rise to desperate behavior. If by states, extreme violent behavior tends to be rationalized as ‘self-defense,’ ‘military necessity,’ or ‘counterterrorism,’ and governmental claims of legal authorization tend to be upheld by judicial institutions. If even nonviolent acts of resistance by individuals associated with dissident movements occur, then the established order and its supportive media will routinely describe such acts as ‘terrorism,’ ‘criminality,’ ‘political extremism,’ and ‘fanaticism,’ and the behavior is criminalized, or at best exposed to scorn by sovereign states and their civil society establishment. Statist forms of combat almost always rely on violence to crush an enemy, while the desperation of resistance sometimes takes the form of inflicting hurt upon the self so as to shame an oppressor to relent or eventually even surrender, not due to empathy or a change of heart, but because fearful of alienating public opinion, intensifying resistance, losing international legitimacy, facing sanctions. It is against such an overall background that we should understand the role of the hunger strike in the wider context of resistance against all forms of oppressive, exploitative, and cruel governance. The long struggles in Ireland and Palestine are among the most poignant instances of such political encounters that gripped the moral imagination of many persons of conscience in the years since the middle of the prior century.

Those jailed activists who have recourse to a hunger strike, either singly or in collaboration, are keenly aware that they are choosing an option of last resort, which exhibits a willingness to sacrifice their body and even their life itself for goals deemed more important. These goals usually involve either safeguarding dignity and honor of a subjugated people or mobilizing support for a collective struggle on behalf of freedom, rights, and equality. A hunger strike is an ultimate form of non-violence, comparable only to politically motivated acts of self-immolation, physically harmful only to the self, yet possessing in certain circumstances unlimited symbolic potential to change behavior and give rise to massive displays of discontent by a population believed to be successfully suppressed. Such desperate tactics have been integral to the struggles for basic rights and resistance to oppressive conditions in both Palestine and Ireland.

An unacknowledged, yet vital, truth of recent history is that symbolic politics have often eventually controlled the outcomes of prolonged struggles against oppressive state actors that wield dominant control over combat zones and uncontested superiority in relation to weapons and military capabilities. And yet despite these hard power advantages thought decisive in such conflict, the struggle from below persists, often at great cost, yet in the end surprises the world, and sometimes itself, by prevailing. It may be helpful to remember that it was the self-immolation of Buddhist monks in Saigon during the 1960s that was considered ‘a scream of the culture’ in defiant reaction to the American led military intervention, which many credited with reversing the course of the conflict. It led Vietnamese scholars to interpret these extreme acts of solitary individuals, endowed with the highest civilizational credentials of moral authority, as shifting the balance of forces in Vietnam in ways that then and there doomed the seemingly irresistible American military resolve to control the political future of Vietnam. These acts of self-immolation didn’t end the war, but to those with insight into Vietnamese culture it did signal an outcome contrary to what the war planners in Washington confidently expected. Tragically before Washington brought itself to acknowledge defeat, the Vietnam war persisted for a decade, ravaging the land and bringing great suffering to the people of Vietnam. Self-immolation, setting oneself on fire as an irreversible instance of self-sacrifice, carries the analogous logic of a hunger strike to a final conclusion. Depending on the actor and context, self-immolation can be interpreted either as an expression of hopeless despair or as a desperate appeal for a just peace.

It was the self-immolation of a simple fruit and vegetable vendor, Mohamed Bouazizi in the Tunisian town of Sidi Bouzid on December 17, 2010 that called attention to the plight of the Tunisian people, igniting a nationwide uprising that drove a corrupt dictator, Ben Ali, from power. Bouazizi, without political motivation or spiritual authority of the Buddhist monks, sparked populist mobilizations that swept across the Arab world in 2011. Somehow Bouazizi’s entire personal self-immolation was the spark that set the region ablaze. Such a reaction could not have been predicted and was not planned, yet afterwards it was interpreted as somehow activating dormant revolutionary responses to intolerable underlying conditions.

Without doubt, the supreme example of triumphant symbolic politics in modern times was the extraordinary resistance and liberation movement led by Gandhi that merged his individual hunger strikes unto death with spectacular nonviolent forms of collective action (for instance, ‘the salt march’ of 1930), accomplishing what seemed impossible at the time, bringing the British Empire to its knees, and by so doing, restoring independent statehood and sovereignty to colonized India.

Both the oppressed and the oppressors learn from past successes and failures of symbolic politics. The oppressed view such behavior as an ultimate and ennobling approach to resistance and liberation. Oppressors learn that wars are often not decided by who wins on the battlefield or jail house but by the side that gains a decisive advantage symbolically in what I have previously called ‘legitimacy wars.’ With this acquired knowledge of their vulnerability to such tactics, oppressors fight back, defame and use violence to destroy by any means the will of the oppressed, and their global support network, to resist, especially if the stakes involve giving up the high moral and legal ground. The Israeli leadership learned, especially, from the collapse of South African apartheid not to take symbolic politics lightly. Israel has been particularly unscrupulous in its responses to symbolic challenges to its abusive apartheid regime of control. Israel, with U.S. support, has mounted a worldwide defamatory pushback against criticism at the UN or from human rights defenders around the world, shamelessly playing ‘the anti-Semitic card’ in its effort to destroy nonviolent solidarity efforts such as the pro-Palestinian BDS Campaign modeled on an initiative that had mobilized worldwide opposition to South African apartheid. Notably, in the South African case, the BDS tactic was questioned for effectiveness and appropriateness, but its organizers and most militant supporters were never defamed, much less criminalized. This recognition of the potency of symbolic politics by Israel has obstructed the Palestinian liberation struggles despite what would seem to be the advantageous realities of the post-colonial setting.

Israel’s version of an apartheid regime evolved as a necessary side effect of establishing an exclusivist Jewish state in an overwhelmingly non-Jewish society. This Zionist project required that the Palestinian people become experience the agonies of colonialist dispossession and displacement in their own homeland. Israel learned from South Africa techniques of racist hierarchy and repression, but they were also aware of the vulnerabilities of oppressors to sustained forms of non-violence that validated the persevering resistance of those oppressed. Israel is determined not to repeat the collapse of South African apartheid, which explains not only repression of resistors but sustained efforts to achieve the demoralization of supporters that comprise the global solidarity movement, especially those in the West where Israel’s geopolitical backup is situated.

A similar reality existed in Northern Ireland where the memories of colonies lost to weaker adversaries slowly taught the UK lessons of accommodation and compromise, which led the leaders in London to shift abruptly their focus from counterterrorism to diplomacy, with the dramatic climax of the Good Friday Agreement in 1998. Israel is not the UK, and the Irish are not the Palestinians. Israel shows no willingness to grant the Palestinian people their most basic rights, even withholding COVID vaccines, yet even Israel does not want to be humiliated in ways that can arouse international public opinion to move from the rhetoric of censure toward the imposition of sanctions. The Israeli Prison Service doesn’t want Palestinian hunger strikers to die in captivity, not because of empathy, but to avoid bad publicity. To prevent such outcomes, Israeli prison authorities will often attempt forced feeding, but if that fails, as it usually does, then they will bend the rules, make some concessions, including even arrange a release when it is feared that a hunger striker is at the brink of death. Palestinian prospects are more dependent than ever on waging and winning victories in the domain of symbolic politics, and Israel, with the help of the United States, will go to any length to hide tactical defeats of this sort in this longest of legitimacy wars.

It is against such a background that these writings were collected, with Palestinian and Irish contributions interspersed throughout the volume to underscore the essential similarity of these two epic anti-colonial struggles. What gives A Shared Struggle its authority and persuasive power is the authenticity derived from words of those brave men and women who chose to undertake hunger strikes in situations of desperation and experienced not only their own spirit-enhancing ordeal but the pain of loss of nearby martyred fallen comrades, grieving families, and their common effort to engage the wider struggles for rights and freedom being carried on outside the prison walls. Despite the vast differences in their respective struggles against oppression, the similarities of response created the deepest of bonds, especially of the Irish toward the Palestinians whose oppressive reality was more severe, and has proved more enduring. The inspirational example of the Irish hunger strikers who did not abandon their quest for elemental justice at the doorstep of death was not lost on the Palestinians. At the end of their protest in 1981 the Irish prisoners obtained formal recognition of their political movement. They also were finally granted recognition by the British that Irish resisters deserved to be treated as ‘political prisoners,’ and not common criminals, came after the Good Friday Agreement when they were released from prison, a political amnesty in all but name. The struggle for Irish independence has not let up, continuing in all of Ireland as an unresolved quest.

Ever since visiting Belfast two years ago I have been struck by how the Irish revolutionaries, despite these vast differences in circumstances and goals, regard their struggle as being reproduced in its essential character by the Palestinian struggle, and have a robust solidarity movement that regards Palestinian freedom as one of the incomplete aspects of their own struggle. The wall murals in the Catholic neighborhoods of Belfast exhibited these affinities, recognizing that oppression is not confined within the sovereign space of nations, but is a transnational reality with a boundary-less community of dedicated individuals. Solidarity and opposition express an unarticulated and largely unacknowledged global humanism. While the Palestinian challenge may be more epic in quality and intensity, the Irish struggle was also waged as a matter of life and death, and even more fundamentally, as an insistence that humiliation, indignity, and servitude were unendurable conditions that produced and justified martyrdom.

Among the great differences in these two national narratives that form the background of these separate renderings of the hunger strikes concerns the impacts of the international context, and especially the role of the United States. With regard to Ireland, American public and even elite opinion was strongly supportive of Catholic resistance in Northern Ireland, and the U.S. mediational role was exercised with an impressive spirit of neutrality. With respect to Israel, the U.S. pretends to play a similar role as intermediary or ‘honest broker,’ yet with zero credibility. It should surprise no objective observer that these diplomatic maneuvers associated with a faux peace process produced only frustration and disappointment for the Palestinians, in part, due to Washington’s unabashed and unconditional material and diplomatic partisanship, including siding with Israel even when it flagrantly violates international law or repudiates the UN consensus on the contours of a just peace. Such futile diplomacy allowed Israel to continue building its unlawful settlements for year after year, compromising Palestinian territorial prospects and resulting in not a single adverse consequence for Israel.

The media treatment of the two struggles reinforced this disparity. The Irish hunger strikes were given generally sympathetic prominence in mainstream media outlets, with Bobby Sands’ name and martyrdom known and respected throughout the world. In contrast, outside of Palestinian circles only those most engaged activists in solidarity efforts are even aware that lengthy and life threatening Palestinian hunger strikes have repeatedly occurred in Israeli prisons during the last several decades.

This denial of international coverage to such nonviolent resistance acts helps reinforce Israeli oppression and uphold the Israeli anti-terrorist narrative, and should be viewed as a kind of transnational complicity. Naked power and geopolitical ‘correctness,’ rather than elemental morality is allowed to dominate the discourse. In the background is the bankruptcy of liberal Zionism. For many years, leading liberal journalists, such as Tom Friedman of the New York Times, were counseling the Palestinians that if they gave up violence, and appealed to Israeli conscience by having recourse to nonviolent forms of resistance, their political grievances would be addressed in a responsible manner. Palestinians responsively launched the first intifada in 1987, and soon realized that those meddlesome liberal establishment well- wishers in the West were quickly muted as soon as Israel responded violently, seeking to crush this most impressive nonviolent and spontaneous mobilization of those Palestinians fed up with living under the rigors of prolonged occupation.

Silence about Palestinian hunger strikes reduces the global impact of these expressions of desperation, which makes this publication of additional significance. It exposes readers to a series of separate stories of heroism under intolerable conditions of Irish and Palestinian imprisonment. This collection also offers a corrective to the virtual media blackout in the West that denies coverage to Palestinian resistance including even, as with hunger strikes, when resistance turns away from violence, and expresses a desperate last resort. Again, the contrasting international media binge coverage of the Irish hunger strikes definitely contributed to the liberating Irish diplomatic breakthrough that might otherwise not have occurred, or at least not as soon as it did.

We notice in these stories collected here, that the Irish contributions situate their recourse to hunger strikes protesting prison conditions more explicitly in the wider struggle of the IRA, while Palestinians stories tell more graphically of the agonies of prolonged imprisonment in Israeli prisons. Our attention is drawn to the denial of minimal international standards of treatment, including failures of medical treatment, bad food quality, denial of family visits, inadequate exercise, and sadistic prison responses ranging from force-feeding to tempting hungry strikers by placing tantalizing foods in prison cells. Yet both Irish and Palestinian styles of witnessing emanate from the same source–how to respond to the desperation felt by intolerable abuse in conditions of imprisonment, and yet carry on the wider struggle for freedom and rights that landed them in prison.

In reading these harrowing statements of broken families and broken hearts, we should not be deceived into thinking that we are reading only about events in the past. There are currently about 4,500 Palestinian prisoners, including 350 imprisoned under ‘administrative detention’ provisions copied from the British Mandate colonialist administration of Palestine, under which Palestinian activists and suspects can be jailed indefinitely without any specific charges or even a show of some evidence of wrongdoing. Many of the individual hunger strikes take this dire step of a hunger strike without an end date to protest against the acute and arbitrary injustices associated with administrative detention, which appears to be a technique used by Israel to demoralize the Palestine people to an extent that makes their resistance seem useless.

Maher Al-Akhras was close to death in an Israeli prison when freed on November 26, 2020, having mounted a hunger strike for an incredible period of 103 days as a specific protest against being held under administrative detention, that is, without any charges of criminality. Hardly anyone outside of Palestine and the Israeli Prison Service knows about his ordeal. Al-Akhras words when teetering on the brink of death encapsulate the common core of these unforgettable shared stories: my hunger strike “is in defense of Palestinian prisoners and of my people who are suffering from the occupation and my victory in the strike is a victory for the prisoners and my Palestinian people.” In other words, although such an extreme act of self-sacrifice, while being intensely individual, is above all an expression of solidarity with others locked within the prison walls but at the same time often the only form of resistance available to an imprisoned political militant. Such a commitment has its concrete demands relating to prison conditions, but it should also be understood as a metaphor encouraging a greater commitment by all of us, wherever situated, to the struggle that needs to be sustained until victory by those on the outside who are daily subjugated to the policies and practices of the oppressor state.

These stories are here to be read, but the publication of such a collection is also a global solidarity initiative supportive of the Palestinian struggle. The suffering and rightlessness of the Palestinian people has gone on far too long. We now know that the UN and traditional diplomacy have failed to achieve a just solution. Given these circumstances, it becomes clear that only the people of the world possess the will and potentially the capabilities, to bring justice to Palestine. It Is an opportunity and responsibility posing a challenge to all of us. We need to find what ways are available to support those brave and dedicated Palestinians who have paid for so long the price of resisting Israeli oppression.

Palestinian and Irish hunger strikers who contributed their stories to this memorable volume deserve the last word here. Mohammed Al-Qeeq says this: “It is not just about my freedom, but rather the freedom of every soul who curses the injustice as I do.” From Mohamad Alian these words: “In our minds the prison became our cemetery.” And from Pat Sheehan this assessment of the hunger strikes: “It was, and remains, one of the most defining and momentous periods in Irish history.” Finally, Hassan Safadi: “The look on the faces of the Zionist officers who wanted me dead, will never leave me, but I stared right back at them.”