Video and Text Transcript

Transcript of the video:

Helena Cobban (00:00)

Hello, everybody, and welcome to session number seven of our webinar series, The “Ukraine Crisis: Building a Just and Peaceful World.” It's Wednesday, March 23, and we're lucky to have with us today two guests who have a broad understanding of the United States' role in the world and a sharply intelligent way of explaining international issues. They are Phyllis Bennis, a fellow at the Institute for Policy Studies here in Washington, DC, and its offshoot, the Amsterdam-based Transnational Institute at IPS. Phyllis directs the New Nationalism Project, which works to change American policy and to democratize and empower the United Nations and to free it from US domination. Good to see you, Phyllis.

Phyllis Bennis (01:25):

Great to be with you, Helena. Good to be with you, Richard.

Helena Cobban (01:30):

We also have Indi Samarajiva, a Sri Lankan writer who, as it happens, grew up in Ohio and is a keen observer of the imbalance between the global north and the global South. You can follow Indi's unbelievably prolific and well crafted writings at Indi.ca or via his account on Medium. Indi is with us from Colombo, Sri Lanka, where it's currently midnight. Indi, thank you for staying up so late to be with us.

Indi Samarajiva (02:04):

No problem. Thank you. Nice to be here with you all.

Helena Cobban (02:08):

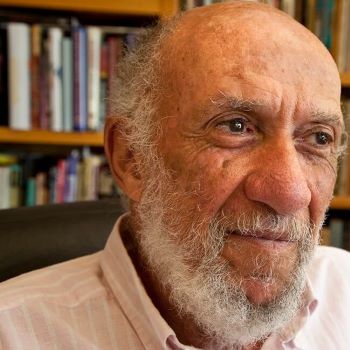

And my co-host here is Richard Falk, a distinguished international jurist who I hope needs no introduction. We are much looking forward to delving deep with both our guests into crucially the matter of the impact of this crisis in Ukraine on the peoples of the Global South, and how together, we might all move forward to build a more just and sustainable world order. So let me hand over to you, Richard.

Richard Falk (02:36):

Well, let me welcome our guests, as you have done so graciously and echo your words of suggesting that we explore further what can be done to stop the killing in Ukraine and what are the broader ramifications of what's happening in the Ukraine for the world economy, for peace and democracy throughout the world. I think people forget that it's not only Ukraine that will be victimized by the continuation of the war, but lots of people in all parts of the world that will suffer from the adverse consequences, particularly the shutdown of food exports from Ukraine and Russia, which will affect particularly the people in the Middle East and North Africa. So I look forward to these two guests who have lots to say, and we will listen with anticipation.

Helena Cobban (04:03):

Today's Webinar is the seventh of our planned eight sessions. Our earlier sessions, which involved a great roster of guests, were all excellent. You can access the videos, audios, and transcripts of those sessions and a lot more information about this project at our website, www.justworldeducational.org. The video of today's session will be uploaded there soon, too. And after that, the links to the audio version and the transcript. Today's conversation is projected to last roughly 45 minutes. After that, there'll be a chance for questions from the attendees, which we asked you to put into the Q and A box. Also, in these emotionally taxing times, we ask for civility from all attendees, both in the chat box and also, if you're invited, on air there, too. So first, I'll turn to you, Phyllis Dennis, and ask you to provide your view of the impact of the Ukraine crisis on the global order and in particular on the global South, with some pointers on how global justice activists worldwide should be moving forward.

Phyllis Bennis (05:21):

Thanks, Helena. This crisis that we are facing right now, based on the war in Ukraine from the Russian invasion, really brings to mind the notion that history, as we understand it, begins with when you start the clock. If we could start the clock right now. And on one level, we need to because of the urgency of the killings, the destruction that is underway resulting from the Russian invasion. There is that moment. But there's also the past 30 years where we've seen a great deal of provocation from NATO, from the United States and its allies. Provocations against Russia. Of course, NATO's creation was originally against the Soviet Union. When the Soviet Union collapsed and the new Russia emerged, it should have been a moment for NATO to disappear, to say, well, we did it and then disappear, whatever, but to get out of the way, that didn't happen. Instead, they expanded. So there have been a lot of provocations, none of which, in my view, justify the Russian invasion of Ukraine. But that's another moment. There are many moments in a 30 year history that we could look at. Then there's the question of the future.

So I think we need to take into account all of those things at the moment. The urgency of now has everything to do with the enormous humanitarian toll that is underway, the killing of so many people, civilians primarily, but also huge numbers of soldiers on both sides. And, of course, the creation of a multimillion person refugee flow, the largest and fastest refugee flow from Europe since World War II. So we have an immediate need for a cease fire, for the Russian forces to be withdrawn, for Ukraine to make clear that they are going to be a neutral country, say no to NATO, and begin the process of disarmament. All of that is urgently needed right now. We also have to recognize right now the global threat that is underway not only from escalation potentially of this war to a broader regional war and potentially even a nuclear exchange between the world's two primary nuclear weapons states, the US and Russia. And whenever there's a global threat, it's always worse in the global South, where the people are the most vulnerable, where the land is most vulnerable to the environmental results of these catastrophes. All of that vulnerability concentrates in a thoroughly disproportionate focus on the South.

So that's what we need to be looking at just for a moment on the past. One of the things that I think we need to look at is the history of NATO's expansion. Since the collapse of the Soviet Union and the rise of Russia, we've seen, at a moment when many of us believed NATO should disappear. Instead, we saw it expanding greater militarization that was taking place in Europe in particular. But on a global level, suddenly NATO emerges beyond its own territory, starting with taking the lead in the war in Kosovo and then of course, outside Europe, in Afghanistan, in Iraq, in Libya, in other wars way outside of the area of the NATO countries. So that's what we also have to be keeping in mind the dangers that we see right now, the dangers, of course, of escalation nuclearization. This makes it a very different phenomenon than earlier wars that we fought against that were wars initiated by the United States and its allies, the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and Libya and Somalia, elsewhere around the world. And now, of course, we're hearing calls for escalation, we're hearing calls for a no fly zone, and we have to be affirmatively challenging that call.

We know that the idea of a no fly zone sounds great. It sounds like magic. It sounds like something out of Star Wars, a magical shield that's going to prevent all the attacks on people on the ground. Yay, what's not to like? Right? Well, the problem is, as the then Secretary of State Robert Gates said in 2011 when the US was debating a no fly zone against Libya, he said, let's be clear, a no fly zone in Libya starts with going to war against Libya. It starts with attacking Libya. In this case, it starts with the United States and NATO attacking Russian anti-aircraft battalions across Ukraine and potentially inside Russian territory just over the border. The environmental catastrophe that can come from this war, which again will have enormous impact, particularly in the South, the rehabilitation of oil producers like Saudi Arabia and other criminal regimes. All of that is risked from this war, the imposition of sanctions, which are now more popular than ever, despite the enormous impact that they're having on the people of Russia, without really much impact, at least so far, on the oligarchs and the other powerful people in Russia.

And crucially, we're seeing militarism spreading across Europe, we're seeing NATO bigger and stronger than ever, countries like Finland and Sweden talking about joining NATO, greater dependency on the US military and purchase of US weapons, Germany so long refusing to put massive amounts of money into the military, now saying they're putting in €100 billion into the German military right away and soon will be at 2% of GDP, which will have enormous impact on things like health care and jobs and education and all the things that Europe has liked to be known for. And who's making a profit from this? Who's gaining from this? It's the producers of military weapons. The other day, the CEO of Raytheon talked about how we were getting worried with the US pulling out of Afghanistan. He didn't have to say, this was to a group of shareholders in Raytheon, he didn't have to say we've made a killing on the US war for over 20 years in Afghanistan. But he went on to say, but we're a little bit optimistic now because we're hearing some interesting news from Eastern Europe. This was two weeks before Russia invaded, so they knew that they were going to make a killing from this war as well.

It's only the arms dealers who profit from this war. But unfortunately, a lot of these lessons that we've seen so long have not been learned. Outside Europe, as Richard mentioned earlier, we're going to see a huge impact on food production that will impact people in the global South more than anywhere else. There is a desperate need for negotiations, for diplomacy, not just as a slogan, but real push for diplomacy. So then the future, what are we looking at? What do activists need to be taking into account? One is that we're coming into a period when NATO will be stronger and more influential than ever, where Europe will become a greater source of military power and alliance militarily with the United States rather than an occasional challenger of US militarism. The hypocrisy we have seen here has been absolutely over the top, more than we've ever seen before. How other occupations are responded to, whether in Western Sahara, Kashmir, especially in Palestine, how the media in the US and in Europe treat other wars in Darfur, in Myanmar, in Somalia, in Yemen, which is to say they mostly don't treat it. They mostly ignore those wars.

And the humanization that we've seen of the victims of war. It has been a model of how it should look for all of these wars, and yet we're only seeing it when white Europeans are the victims. So this is an example, just quickly to finish, the question of refugees, how refugees are being treated, and all of these lessons of racism and hypocrisy and xenophobia gives us an opportunity to say this is what every refugee should receive at a border crossing: a welcome, a humanisation, food, medicine, help for their children, settlement wherever they need to live. When wars break out, we should be seeing 24/7 coverage of what happens to victims of those wars. That's the lesson, I think, for our activists that we have to start the clock now in looking again at this as a model of what we should be demanding for every war, for every occupation, and for every refugee. This is an opportunity for us when this ends.

Helena Cobban (14:20):

Thank you. That's great. That's very eloquent, telling us what everybody should be working for. But now we're going to move to Colombo, Sri Lanka and hear from you, Indi, about your view of the impact of the Ukraine crisis on the global order and in particular on the global South with some pointers as to how you'd like to see global justice activists worldwide moving forward.

Indi Samarajiva (14:48):

Thank you, Helena. Thank you, Phyllis. So you may be wondering what the view of a random idiot from Sri Lanka has to do with Ukraine, which is 6000 km away. And I think that's a very good question. And I think that's something that people within what I call White Empire, which is America and whoever is following along with them these days. That's what I think people within those countries should ask themselves as well because we've sort of gotten into this world where the opinion of every random person in Idaho or London or Nottingham ends up being life or death for people in other random parts of the world and also with the opinions of these people get manipulated in order to, as Phyllis was talking about, make money for a lot of oligarchs. And it becomes this sort of TV show to people in these countries, something that you need to have a take on, something that you need to have an opinion on. And I've been a part of that when I lived there. I also thought like, hey, war, fun, we can talk about this, we can debate this. But we've been through decades of war and we've seen millions and tens of millions of people displaced, millions of people killed.

And it didn't start with Ukraine. And I think it starts from this hubris that the opinion of people 6000 km away needs to come with bombs and needs to come with no fly zones and needs to come with these terrible life or death consequences for people who are very far away. So when you're asking what are the views of people in Sri Lanka about the Ukraine crisis, honestly, we're not really thinking about it. We have our own problems. And that is also something that people in America and Europe should think about as well because you guys have your own problems. So we have problems with food and fuel which were happening before this and now they're only going to get worse. And we had Ukrainian and Russian tourists here and we tried to help them out by giving them places to stay. So I think helping people who are victims of this thing is very important. But have people in Sri Lanka been like, hey, yeah, should we go impose a no fly zone over Ukraine? No, that's not a conversation we have. And that's not really a conversation you should be having either, because your village idiots are no better than our village idiots.

And none of our idiots should be imposing policy on the other side of the world. So when you ask what should activists be doing? I think of the Hippocratic Oath, which is do no harm, because there's this sense, and I grew up in America, there's a sense when you watch the TV shows and you're like, oh, we need to go and save the day and get the crew together and bomb our way through things. And I was 17, 18 when the Iraq war started, and I thought that as well. And I'm ashamed to say that. And if you haven't seen after all of this bloody experience that it just makes things worse, then I don't know what to tell you, because we've all lived through this over and over again, and so many people have died. And every time America tries to go in, they just sell more bombs to drop on generally poor people, and it just makes things worse. So I tried to return to that idea of just do no harm, which I'm telling you people, and you guys call it the global South. We're actually the global majority. You should join us.

But people in the global majority, we just don't really have that option. People in Sri Lanka are not sitting around thinking about what do we do about Ukraine? Like, what do we do about Yemen? And yet as a consequence, we don't make those problems worse. I'm not saying we're like better people, but we seem to have better results just by not going and meddling in every damn problem and honestly bothering each other a lot. But that's another story. So as for my views on Ukraine, so as I said, I'm just another village idiot, but you inflict your village idiots on us all the time. So you might as well get one from here. I would just start by saying war is hell. Like, I've lived through war mostly on the safe end, but I've seen parents covered in their children's blood. I've seen children who are maimed in wars and they didn't have it coming. And so all this debate is well over their heads. And I think people forget that. And yet there's that sort of hubris when you see that, yeah, war is hell. You think that maybe more war is going to get out of that hell, but it's usually just more hell.

And I think people sort of need to have some awareness of that. For example, when people talk about Ukraine, there's only two options there. Either you let Ukraine surrender and negotiate something or just negotiate. You can call it whatever you want. Or you put American troops on the ground there, or you bomb Russian positions and start World War Three. And none of those are good options. So maybe just sitting back and doing nothing might be the best option. And not this, like, TV drama where you have this TV President that you need to support. And I see people honestly getting horny over Zelensky and stuff. I'm just like, what are you doing? Like, this is war. There aren't heroes like that in this. And if you're really against war, then like Phyllis was saying, NATO shouldn't have been there. If China had built a military alliance out of Pakistan and Bangladesh and Sri Lanka, and they are integrated with Pakistan and Bangladesh to some degrees, they would invade Sri Lanka. India would invade Sri Lanka. They've done it before. But if you put, like something threatening in Sri Lanka, they would invade us.

And I'm not saying, I mean, provoke is a loaded thing, but we kind of would have had it coming. It's very threatening when you're surrounded by someone else's weapons. And the fact that NATO continued existing after the Warsaw Pact disappeared, I don't know what NATO is at this point. It seems to be just like a white supremacist organization. So that's a problem. And if you're looking at reducing war, then maybe reduce those war machines. It's not about using those war machines to like bomb war out of people. We've been trying that for 20 years, or you've been trying that. We've just been bombing ourselves. When you're talking about the global order, yeah, I think it is changing, because when you look at the people who sanctioned Russia, it's not us, it's not the global majority. So it looks like the old nonaligned movement, which is just like, we don't want any part of this going down. Like we're trying to feed our families, we're trying to keep the lights on. So in Sri Lanka, we've talked about opening up credit lines with Russia. We just need food and fuel and we can't make that situation any better.

And we just need to put food on our tables. And I think China and Russia have opened up credit lines because, again, there's not much China can do to make that situation better. And keeping food and resources flowing is kind of important for our families. And so you can see sort of like Joe Biden was talking about a new world order where you can see an actual new world multipolar order where people are trading in their own currencies. And in a big way, the US is sort of destroying their own dollar hegemony because you can't keep sanctioning, you can sanction Iran and Venezuela. Those are smaller countries. It's cruel and evil. But once you start sanctioning Russia, and then they've even started threatening India with sanctions, then pretty soon you've sanctioned yourselves into a corner. And the dollar hegemony that enables you to bail yourself out of problems, that enables you to run this eternal war machine, like, at some point that golden goose will be plucked. That seems to be happening because we're all opening up our own lines of communication because we don't want to deal with your crap anymore. But the final thing I add is this is just all very unpredictable and dangerous.

So we're playing with World War III here. We're playing with nuclear weapons. We're playing with food supplies which affect people in Africa, which affect people in the Middle East. We're playing with nickel supplies, we're playing with titanium supplies, steel, all these underlying parts of other things which have other unintended effects. And then we're throwing climate change in there, and you're just getting the recipe for chaos, violence, and a lot of problems all over the world. And the best thing we can do now is not jump in and fix these problems with bombs. But I'll return to the Hippocratic Oath, which is just try and do no harm.

Helena Cobban (22:57):

Thank you. Wow. There is a lot to think about. And thank you for bringing alive on our screen some of the thoughts that you've already been developing in your amazing daily essays. So, Richard, what are your first thoughts on hearing from Phyllis and Indi?

Richard Falk (23:16):

Well, they've said a great deal that needs to be said and said it very eloquently and perceptively, and we could be talking for hours about the importance of the various themes. What I'm trying to say is that both Indi and Phyllis gave us insight into the context of the Ukrainian war and also why that context keeps generating these kinds of destructive tragedies that befall on people. And that slogan that Indi kept repeating of do no harm is something Americans, above all others on the planet, should meditate upon. What that would mean. What would that mean if you take those words seriously and not just as a slogan? I would point to one other thing. Phyllis covered the ground very impressively in that short time she spoke. One thing she didn't say so much about, which I think is relevant, is how the US handled the end of the Cold War. She did say, and I think we all agree that it was an opportunity to shift the vector of international relations by terminating NATO at the same time that the Warsaw Pact was dissolved. But I think there's a broader reflection on the end of the Cold War, and that was the sense that instead of finding a way of strengthening UN, strengthening international law, taking the opportunity to get rid of nuclear weapons, there was a triumphalist mood that suggested now the US could impose a global system of security, and only the US would have the geopolitical prerogative of going anywhere in the world to pursue our strategic interests.

And as I've said before, we should remember that the UN was designed to give the geopolitical actors an exemption from international law. The veto power essentially says the important states in the world, important as of 1945, at the end of World War II, they're no longer the important States, but the US and Russia still are, and China. And the idea was the League of Nations failed because it tried to exclude geopolitics from its operations. The UN will succeed if it allows the geopolitical actors to have discretion over the pursuit of their strategic objectives. And so this sense that we're now in a unipolar world and part of what is happening in Ukraine is a proxy geopolitical war between Russia and the US, because Russia is in one sense, protecting its traditional sphere of influence. And those spheres of influence were acknowledged as Soviet prerogative during the entire Cold War. The West was prudent enough to never to militarily intervene in East Europe despite terrible military interventions in Hungary, East Germany and the Czech Republic. But after the Cold War, there was this idea that no one else but the US, with NATO in the background, has any prerogative to act outside its territory.

And that was a unilateral kind of radical reform of geopolitics. One way of looking at it is to say the US, instead of abandoning the Monroe Doctrine, has globalized it and has globalized it in ways that validate our use of international law as a way of objecting to what our enemies and adversaries do. But it's no inhibition on what we do. So I think this is a moment for self criticism and geopolitical reflection on the world order dimension of international society, which is based on this combination of law and geopolitics.

Helena Cobban (30:08):

Thank you, Richard. I've heard a lot about, well Indi was great, reminding us that the global South is the global majority, which too often is forgotten here because we look at contests between white powers between Ukraine and NATO on the one hand and Russia on the other. I remember when I was in Lebanon as a correspondent, and I would talk about East versus West, and some of my friends there would say, you know, Moscow is actually west of us. So you're talking about two Western powers, Western white powers contesting between them. And there is this sense that we're talking about something that's internal to Europe, but it strikes a big, a potent chord here in the United States, where most people in the political elite are of European origin. So you have these pictures of distraught Ukrainian mothers and babies and whatever flooding into our media. I have sat through so many Israeli invasions of Gaza or of South Lebanon or US Wars in the region, and you never get that kind of blanket coverage of the distress of the victims. Indi, I wanted to ask you about the double standards that the media based in NATO countries apply to stories of war inflicted suffering in Ukraine versus the exactly parallel stories from Palestine, Iraq, Somalia.

I mean, Phyllis mentioned these. Do those kinds of NATO based narratives pervade the global South as much as they do our countries, or do you have alternative narratives there?

Indi Samarajiva (32:30):

What I see, I kind of filter out some people in my own media consumption, but people can see the hypocrisy for sure. So, I mean, people down here, we know that right now in Afghanistan, people are being starved to death. I tried to send some money from here and because everything is so screwed up, like, we can't even do that because they are isolated and left to die. And so those are our neighbors. Like, they have a really good cricket team. So during the cricket World Cup, we could see how hard it was for those guys. And so we connect to each other in those ways. So we know that's happening to people that we play cricket with here while there's honestly, these crocodile tears being cried for people that look like Europeans. So, yeah, we're definitely aware of the I mean, people in the White Empire haven't taken the Hippocratic Oath. They've taken an oath of hypocrisy. So their invasions are interventions, and it's for people's good. But if someone else invades, then it's an invasion. And then those people from the people I follow online. I also know that when you get to the Polish border and the people in Poland are quite open about saying that they're letting Ukrainian, like, white people in and they're pushing Black people back. And they've said, like, I saw Polish officials saying, this is what I was elected to do. We're protecting our population. This is why we don't have terrorism. So we can see that. And it's quite galling because it's just like how many of us how many people like me need to die to equal one person? I increasingly think it's infinity.

Helena Cobban (34:06):

That’s depressing. Phyllis, how about your take on the kind of the media double standards in this country?

Phyllis Bennis (34:15):

It's shocking and not at all surprising because it's a consistent pattern that we've seen over the years, the kind of 24/7 coverage. I mean, I've been looking at, I still get the papers as paper, and looking at The New York Times and The Washington Post every morning above the fold, front page, five, six, seven separate articles on the war in Ukraine, huge pictures, mostly showing victims. And I keep thinking, what if these had been the pictures from 2014 in Gaza, from Operation Cast Lead in 2008 and ‘09 in Gaza? Would the most recent assault on Gaza in 2021 have happened, or would it have been different? Because this has an impact. When we think of victims of war, this is now the image that people in this country are going to have. And it goes directly to this question that emerged, what Indi was saying about the idea of do no harm, of the Hippocratic Oath. There's something that during the first Gulf War, we used to call the CNN factor, and later it became the Twitter factor, the brief but very concentrated attention to a given struggle somewhere, a human rights violation, an attack by a government against a population, whatever it was.

And the instinct that was a common one in this country, and it comes from a humanitarian component says we've got to do something. And that has immediately turned into we've got to do something military. So that the notion is either let them get away with it, as we heard after 9/11, or go to war. That's never the range of options. That's never the only two options, right? There are always things to be done, supporting refugees, humanitarian aid, rebuilding shattered countries, stopping the shipment of weapons around the world, particularly illegal weapons that we know are illegal and are being used illegally in violation of US law as well as international law. All of these things are possible and are called for. This is what our social movements, the anti war movement, others, have called for war, after war, after war. And we still see the same kinds of responses. We've got to do something, and that means something military. So if it's Yemen, well, that means we send some more money to the UN to buy some food. But at the same time, we sell all the weapons they want to this criminal regime in Saudi Arabia and the UAE to slaughter more Yemenis.

So all of that goes on simultaneously. And we only see the one part of it. We only see the one part of it. The difference this time has been not just the scale, but the time. This has been going on now for a month, and our press has been focused on almost nothing else. And we don't remember the lessons. I just saw the news that Madeleine Albright just died. For many, she'll be remembered as being the first woman Secretary of State in this country. I think for most of us on this call and maybe most people listening, she'll be always remembered for what she said about the 500,000 children in Iraq that were killed by US sanctions in the first five years of sanctions after the first Gulf War, where she said, we think the price was worth it. We think the price was worth it. 500,000 children. She didn't challenge the numbers. The numbers, in fact, were a little bit uncertain. It was about that amount. She didn't say, well, we're not really sure. She just said, yeah, we think the price was worth it. And I always wanted to ask her, you know, you have two daughters.

If they were among those 500,000 children, would you still say the price was worth it? But these were Iraqi children, so they were numbers. We didn't see photographs of those Iraqi children on the front pages of our newspapers the way we are now seeing Ukrainian children day after day. And those Ukrainian children should be on the front pages of our newspapers when there is this kind of mass slaughter underway. We should be seeing those pictures. We should be seeing a new humanisation of who are the victims of this war. And it should happen in every war, not just when it's white Europeans, not just when it's an allied country against Russia, who's one of our identified opponents.

Helena Cobban (39:09):

If the only tool you have is a hammer, then everything that emerges is going to look like a nail. And the US media and public culture has been based on a glorification of physical violence and domination for so long. That's what you see when people are saying we've got to do something. That something is always military. And I mean, I've been struck watching a few news conferences where the White House Press Secretary stands up and the media are all corporate media competing to say, what about a no fly zone? What about the MiGs? And that's all that they want to ask about? They don't want to ask about, how about Zelensky calling for negotiations? What can we do to support negotiations and an immediate ceasefire? The titans of the corporate media just want this thing to go on and on and on. And I find that extremely manipulative, which actually brings me back to the Global South. And I'm sorry indeed, that here you have to represent not only the entire global population of people who are under 40 years old, but also the entire population of the Global South, whether they are under 40 or over 40.

But do you actually see that the government leaders in the Brics countries or other countries of the Global South can push for negotiations, push for a ceasefire, push for a regulation of all the outstanding issues to the bricks countries or other countries of the Global South have a role to play, have the possibility of doing that.

Indi Samarajiva (41:02):

The Brics countries include Russia, and I think they've been asking for negotiations, and I think they are negotiating. India is a very, I was just visiting family in Kerala. So India, a lot of their military equipment is Soviet, so they're flying MiGs and so on. So they depend on Russia, and the US is trying to pressure them to sort of cut that off. They've gotten Europe to cut off from Russian whatever. But India is a real pressure point there. And people in India, India has been kind of like somewhat reliable part of the Empire. But people within India are questioning that. Now, that's the sort of pressure that I don't know what sort of pressure that puts on it, but that fractures. If you're suddenly pissing off Russia, China and India, and then everybody else is not aligned, then you have a bit of a problem. The Indians I know, when the US has floated stuff about sanctioning them for buying Russian arms, the Indians I know are pretty pissed about that. So that's a form of pressure in itself. I'm not like a geopolitical Svengali, but pissing Indians off is generally problematic. They're very loud. That is a form of pressure in itself.

I just wanted to comment on something Phyllis said. Madeleine Albright, she had this quote, I remember, which was I think she screamed this to Colin Powell, which is that, we have this great military. We need to use it. Yeah, I think about that a lot because, I mean, Phyllis is talking about the media and how it could portray conflicts better, but I think there's also a conflict of interest there. Like if it bleeds, it leads. So in the mafia, they're a saying, make your bones. So you kill someone to enter the mafia. But CNN effectively made its bones on the Iraq war. And I remember as a child, the first Iraq war, I remember as a child, I have this memory quite vividly, cutting out a bomber, like an if 30 something or like an American bomber. I remember cutting around the bombs on it, and I thought it was fun. And that's sort of like what I'm not representing the South here, but that's what I grew up in America, and war was something I watched on TV and we were the good guys and there were bad guys and it was fun. I remember watching CNN during the first Iraq war and watching like fireworks.

So it's like the circuses to me. So it's like the Roman circuses. People like watching other people get eaten by lions. It's problematic, especially with America. My general rule is just follow the money. So the media makes money on this. Like it's good for business and the arms dealers make money on this. So you, the American population are the ones getting sort of robbed because this is money. You guys could have health care, you guys could have better lives, but you get this bloody circus and no bread.

Phyllis Bennis (43:59):

And right now, 53% of our discretionary federal budget goes directly to the military. And of that $350,000,000,000, almost half goes directly to the war profiteers to these corporations and their overpaid CEOs. While the privates, the lowest ranking of the US soldiers, make so little money that as of 2017, 230 of them were making so little that their families qualified for food stamps because they couldn't afford to buy food. So this is the disparity that we're seeing of who benefits from these wars. And it goes directly to the question, I think that you hit it right indeed, on this issue of do no harm that needs to be the call of antiwar forces in this country is stop responding militarily to every crisis around the world, most of which you have already caused, through economic oppression, through climate issues, through a host of things. But when they do and then say, well, we've got to do something, that means send the troops. This is why we need the United Nations to be rebuilt into something that can actually have some kind of independent influence and power here right now. We don't have that, as Richard was explaining so brilliantly earlier. And that's a huge problem.

Indi Samarajiva (45:24):

If we're being honest, we're talking about people sort of waking up and changing their minds about these big structural things. And the United Nations emerged out of, not that, but people destroying everything. So I'm sorry to say, but that seems to be the trajectory we're on, which is like in the Hindu Trinity, there's Shiva always comes, who's the destroyer - so I actually think it's Shiva time.

Helena Cobban (45:52):

That's depressing. Really horrible. We have a question from Michael, who says for those of us in the US to do nothing is to capitulate to the immoral and illegal policies and practices of US imperialism. So are you saying that the US anti war movement should do nothing or that the US government should stop intervening in conflicts? Please clarify. And then he notes that many of these local conflicts are a consequence of actions taken by the US government. So, Richard, or any of you, if we're going to follow Indi's advice of, it's better to do nothing than to launch war and support war, what is even better than doing nothing, if you see what I mean?

Phyllis Bennis (46:44):

That's what the government does. Our job is to stop them, which means we can't do nothing. We have to do a lot. We have a ton of work to do. My usual sign off these days on emails is we have a lot of work to do, because stopping this militarized response to each of these things is an enormous task. An enormous task. But it means that we should not be getting into the debates about, well, should it be a no fly zone or would we be better off sending the MiGs? That's not the kind of debate anti war forces should be having. We should be trying to figure out how to stop the further militarization. I always come back to that very frightening little one liner that says I don't really know what kind of weapons World War Three will be fought with, but I know what kind World War Four will be fought with: stones.

Helena Cobban (47:40):

Yeah. Richard, anything to add?

Richard Falk (47:44):

Well, that was Einstein's quote.

Phyllis Bennis (47:49):

Thank you.

Richard Falk (47:52):

Well, I totally agree with what is being said by both Phyllis and Indi on these issues, but it's very difficult to get political traction because Americans aren't dying. One of the problems with generating a robust peace movement or some kind of local activism that has the capacity to be influential with the Congress and the media and the White House, the situation is not receptive to this. That's why I think one has to look at what Americans are losing by this interventionary policy. I think that's one of the things that could translate into political leverage if, as I think is likely, there will be an economic downturn of significant proportions if the Ukraine war continues. I think that emphasis on giving up your own society in order to play this global policing role, which is failing, there's no success story of a post-Cold War intervention. Even if you abandon morality and abandon the relevance of international law from a clearly political point of view, from a realist point of view, these are all losses. Iraq was a loss. Afghanistan was a colossal loss going back to Vietnam. Vietnam was a colossal loss.

And the interesting thing to me is the political elites here cannot learn that lesson, because learning that lesson would undermine the idea that over investing in the military is a rational way of upholding security, and they need to exaggerate threats and the mission of the United States and NATO. In that sense, for all his terrible kinds of impact on American politics, Trump's outlook on geopolitics was healthier than Biden's. I know that's a controversial thing to say, but I think he wanted to get away from, he understood that Iraq was a failure, and he was willing to say it. He said it in a partisan, vulgar way. But the conclusion was more like he, he seemed to be aiming at something that was economistic in the same way the Chinese have pursued an economistic geopolitic. And to compete with China economically and to befriend Russia in that context. I mean, it now looks ridiculous, but compared to what Biden seemed to want, confrontation with China immediately and to exaggerate the threats in the South China seas. And to think of that as an American zone of influence. The American spheres of influence are everywhere on the planet, and that's really a radical form of geopolitics that has never been practiced in the past. Even during the colonial era, there was always a sense of several geopolitical actors that were pursuing their strategic interests. We're living in a very unique moment historically.

Phyllis Bennis (52:52):

I think, except I would say, Richard, I think that's true, but I also think that it is rooted in the origins of the United States as a nation state with a country rooted in genocide and slavery. That's what made this country wealthy and powerful. That's how they got the land and that's how they got money. So I think that that consistency of the no borders on that level, of expansion, borders against people, but no borders against expansion of power and influence. You go all the way to the other end of the continent, and then you go beyond. That's when you start to colonize the Islands in the South Pacific and all of that. It's a huge level of consistent focus on militarism and violence as the nature of how this country came to be. And it really hasn't stopped. I mean, now I think, what you said about the lack of US casualties is a very dangerous reality, because as we see the rise of drone war, for instance, and airstrikes taking over from ground troops, it means that from the US vantage point, there's no blood, and the press doesn't care particularly about the deaths of however many, whether it's tens or hundreds or thousands or hundreds of thousands of Iraqis or Yemenis or others in the South, they care about us lives that might be lost.

And without that, these wars will go on under the radar with all of this money going that way, all of the denial of access to that money for jobs and healthcare and climate and all the things that we need it for. But it's been that way for a very long time. I would say.

Helena Cobban (54:46):

Sorry, Indi.

Indi Samarajiva (54:49):

Yeah, I really agree with what Richard was saying, except when he talked about losing wars, right. I think the great innovation of American Empire is that there's more money in losing wars. So if you lose a war for 20 years, you're selling a lot of bombs. Whereas if you finish it and you use your own government department, it's actually kind of a cost. In the same way Americans discover there's more money in having bad health care. So to me, the way I understand America, a lot is actually mafia movies. So in Goodfellas, there's something called a bust out, which is where you take a restaurant or whatever and you just buy stuff on that restaurant's credit, you buy alcohol, you buy whatever, it just goes out the back door to your friends. You're just making money. The restaurant itself is getting hollowed out. And that's also the private equity business model to a large degree. But I think what's happened in America is a bust out. So elites have figured out that you've got this dollar, which since Nixon or whatever, you can just print whatever and they're like, okay, how do we just get some money out the back door on this?

So they just get some expensive bombs, drop them on poor people, and of course you want to drop them for 20 years. That's like just keep making the money. So that's what I think is happening with America is that you're a lease. It's just a mafia bust out. And at some point in Goodfellas is what they say. Like you can't borrow a buck from the bank and the credit runs out and then you light a match, you light the place on fire. But what's happening with Russia is not like dropping bombs on poor people. If you drop bombs, you're dropping bombs on a quite advanced military. So then at some point your credit is going to run out. So once Russia and China start dealing directly in Yuan or in Rubles, once India and Russia start dealing directly, once Saudi Arabia and China start dealing directly, then suddenly your ability to borrow money and to keep financing these things forever, that runs out. And that's how a bust out ends. So that's what I see happening to America.

Richard Falk (56:48):

I agree with that analogy. But I'd say there's one additional thing. The mafia doesn't have to lie to its constituency. The US government has to lie, and it probably lies to itself, self-delusional in order to be able to sort of look at itself in the mirror. There's an entrapping kind of fundamental dishonesty in denying the outcome of all these failed interventions, every one of them, even Libya, not a formidable country from a power political point of view, was much better off under Qaddafi than it was as a result of the NATO intervention. I think the importance of not being able to learn has led to this momentum that is being played out now so melodramatically in Ukraine that we can't look back. Phyllis was talking earlier about looking to the past, looking to the future. The American policy advising elites can't look back at what has happened since the end of the Cold War and even in the Vietnam phase of the Cold War, because if they look back with minimal critical intelligence, they would have to adapt to the loss of agency by military superiority. National resistance has proved a match for superior military intervention, but at heavy cost to the population. That experience is a site of struggle. But from Vietnam onward, the people on the ground have expelled the interveners. And that's part of the unlearned lesson.

Helena Cobban (59:30):

I just also want to come back to whichever of you it was that mentioned the healthcare model in this country. I was growing up in England in the 1950s at a time when the British Empire was just collapsing. Every week on the BBC, there would be some Black or brown person taking over as President of a newly independent country who two weeks earlier had been in jail and roundly decried as a terrorist. So you would have these scenes on the BBC. The sense of Britishness was changing very rapidly from what my parents and grandparents knew, which is that we had this great, wonderful global empire and whatever on which the sun never set. And what it meant to be British in the 1950s was that we had the National Health Service. That was what made people proud to be British. And we watched Call the Midwife on TV and it's like so nostalgic for me because I'm just saying there is a trade off between military spending and maintaining an Empire and being able to organize something like a National Health Service, and we need to bring that home to people, but also that you can change the meaning of what it is.

Of course, the meaning of being British has changed a lot since the 1950s, and I'm not quite sure after the time in the EU and the time out of the EU and Brexit what it means to be British anymore. But we could change the meaning of being American over time. And to me that this is a real challenge. What would it mean to become a country that really was one that cared for our own citizens, that educated them well and had a decent health care system, rather than one that engages in these failed wars, that just visit misery on people all around the world. We do have one question here from Elizabeth, who is asking what can the antiwar people in the US do better to end the conflict in Ukraine? And maybe I think this is a good place for us to start wrapping up the conversation. What can we in the US do better to end this conflict in Ukraine and prevent it from escalating? So come to Indi first. Tell us from your perspective, white people tell you what to do all the time. So now you tell us what to do.

Indi Samarajiva (01:02:29):

Yeah, I don't know. Buddhism says that the Buddha got to where he got by first actually doing nothing, like by sitting. So he wanted to stop suffering in the world. So he left his wife and children and he went and sat and did what looked like to anybody else like nothing. Like he took clothes from a dead body and he lived as a beggar. And so that would be considered like running away from your problems. I'm not giving anybody advice here, but there is some power, after all the mistakes that your country has made with just like all the mess of media and crap that you're swimming in, there is some value to doing nothing. One of your viewers asked that. And yeah, I did mean that in the sense that your government should not be sending arms and bombing people, but just also as a person, it's stressful, like scrambling all the time to try to solve all these problems in the world. I can't give you advice, but sometimes doing nothing and letting your brain settle. Because look, for me, like, I also believed in these wars at some point, I also believed in America, and it took me, like, my own journey to get there. But sometimes doing nothing is a way to start that.

Helena Cobban (01:04:05):

Thanks. So, Phyllis, what can we antiwar people in the US do to better end this conflict in Ukraine. And I love the idea of sitting in quiet meditation. As a Quaker, that's kind of what I try to do once a week, once a week for a short period of time. But what are the kind of slogans and campaigns and things that we need to get around?

Phyllis Bennis (01:04:31):

I don't think I ever would have made a very good Quaker. I don't do well with sitting quietly. I try to arrive at Quaker meetings a few minutes late so I can avoid the silence at the beginning of the meeting. It makes me nervous. I think we have way too much work to do as a movement, as individuals, at times in a rotating way. Yes. We all need to take a step back and rethink what we're trying to do, rethink what it means to be strategic in our work. We need to do all of that. What I think we need to do right now is first recognize that this is both, there was a question also from Leslie, I think, who asked Richard, but I'm going to usurp it for a second. Whether this is only a proxy war between the US and Russia or that's just one part of it, I would say it's one part. This is also a real war between two countries that is being fought in some ways traditional way on the ground, with people traditionally dying in a traditional ground war. It is also a proxy for the broader Russia versus NATO, Russia versus the US phenomenon that we're talking about.

So I think that we as a movement in the US and hopefully as part of a global movement, need to focus dramatically more on the question of negotiations, keeping in mind that every war ends with negotiations at some point of some sort. The question is when does that happen? Does it only happen after a surrender, after a defeat of one side, and then the winning side just dictates? What will be the terms of the surrender, or does it happen early on and it sort of just drags out while the war continues to fight, which is sort of what we're seeing now in Ukraine that was in some ways the Vietnam model. Talks began in early ‘73 and the war continued until ‘75. So there can be a number of ways this happens. But I think as a movement, one of the things we need to do is education. We have through the 20 years of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, we have achieved a very high component of antiwar sentiment among ordinary people across this country, in small towns and big towns, big cities and rural areas, because people have paid a huge price for it and have seen what the damage has been and have seen that there was no victory to be had.

So by the end of the war in Afghanistan, which began with 88% support back in 2001, we had 76% of people saying the war was never worth fighting. Obviously, a lot of those people were the same ones who 20 years earlier were supporting the war. So they changed partly because we had a movement that was constantly mobilizing, constantly keeping the pressure on, keeping the information out there. So we have to do these educational methods, whether it's webinars like this that are so important in classes with student groups, in social arenas, in churches and mosques and synagogues and all of those places where people gather. And it's hard. This is a complicated one. We're not good in this country as a movement of figuring out what our response should be when the fighters on the ground are from two other countries and neither one is from the United States. Right. What we have to focus on is both that history, what is NATO doing there anyway? Nato was about protecting Western Europe from the Soviet Union and all of that, what are they doing in Ukraine? All of that, and knowing that history, but also knowing that that is not an excuse for this war, and that the urgency of achieving some kind of negotiated settlement.

We know what it's going to look like. We know basically what it's going to look like. There's a few things that are unclear. Will Crimea be recognized as part of Russia? Will there be some level of autonomy for the Donbas regions? Those are a little uncertain. What's not uncertain is that Russia will pull out in some form. Ukraine will be neutral. Ukraine will not be part of NATO. Those are the things that are kind of a given. But what we need to do is push harder for getting to the table. Right now, the negotiations are going on at a level three, four, five steps down from the top leadership, and that's better than not having any. But it's not enough. It's not going to work. There's going to have to be top level negotiations. And that means that some other leaders are probably going to have to engage, whether it's China, whether it's Turkey. This is a huge problem. It's not one that we have any control over. So what we can control is what our government is doing, which is to, say stop the talk about a no fly zone, stop the talk about sending more weapons, and sending MiGs.

The US just put aside $15 billion more for Ukraine, the vast majority of which is for military support, another 800 million that was just approved the other day. This has to stop because all this does is expand the war and extend the time it will be fought. And that means just more people are going to be killed. Our focus right now needs to be on getting negotiations underway that can stop the killing. Then we have an enormous set of tasks about what comes next and stopping the militarization across Europe and around the world, stopping the food shortages that are going to affect people across, particularly across North Africa and the Middle East, but broader than that as well. We've got a lot of work to do.

Helena Cobban (01:10:15):

Thank you. You laid it out beautifully. On Monday, we heard from Anatol Levin of the Quincy Institute, who basically laid out what the framework of a doable peace agreement is. And he said that with the right diplomatic push for this agreement, it could be very speedily won. Or as so many of the Hawks in this country are pushing, the war could go on for another five or ten years. But basically it would still be the same outcome. I mean, all that military pushing would not shift anything, which I think really underlines how important it is to push for negotiations. Now, Richard, I want to give you kind of the last word here. How do you sum up what you've heard from our two guests and what we should all be doing over the coming weeks?

Richard Falk (01:11:14):

Well, I think there's been a very strong consensus about the causes and the solution that we should be striving for. And what you and Phyllis have said most recently about the urgency of stopping the killing and recognizing that the humanitarian crisis and the spillover of the Ukrainian war to the rest of the world will only get far worse if we continue, yet the outcome will likely be the same as it would be if we stopped the killing now. So the cost of continuing a confrontation of this sort, and I agree with what Phyllis said about the question of is this a proxy war only? No, of course it's a war between Ukraine and Russia, as well as a proxy war. But both of those wars are real. And it's important that we stop the killing in order also to stop the proxy war and to not allow the escalation to go beyond Ukraine. That's a real possibility and dangerous with the nuclear dimension being tantalizingly dangled before the public every once in a while. So this is often said, an inflection point, we need to act as if a lot is at stake. And I don't know how that happens, but what we've done in these sessions, I think, is to show the importance of trying to move in directions of peace and nonviolence, respect for international law, respect for the human dignity of people, whatever their color. There's a lot that can be agreed upon. But how to get political traction for this consensus seems to me the lingering question.

Indi Samarajiva (01:14:13):

So I'm still sort of getting a sense that American power should just be used differently. And my point is that you shouldn't have power. I think maybe take the advice or the prescription you get to other countries where you sanction them and you tell them to overthrow your leaders, like maybe you have a general strike, overthrow your leaders, throw their heads over the wall, break up into constituent states, and maybe just stop trying to fix the world, give us a century and maybe just sit the rest of the century out. That's what I would recommend to Americans.

Helena Cobban (01:14:58):

Thank you. Okay. I knew we would get some bracing input from you, Indi. And I'm really delighted that you've been with us because you've sparked so many great ideas. We do have quite a lot more to talk about in general. Sadly, we only have one more session of this current webinar series. So the next session is going to be next Monday, and we're going to actually tackle the topic of nuclear deterrence and the potential nuclear dimension of this crisis, which I think probably we should have done at the beginning. But we're going to have two wonderful people who've worked a lot on these issues. I think honestly, for many Americans, younger ones who didn't live through the Cold War, this is something new. You mean like our country could be hit by somebody else's nuclear weapons. That's not fair. But those of us who lived through the Cold War understood that there was mutual deterrence and mutually assured destruction. So we're going to actually be looking at some of those issues next Monday. Really. It's been such a pleasure and a privilege to have Phyllis and Indi with us. If you're attending this webinar, you can find details of this next session at our website, www.justworldeducational.org, where you will also find the donate button that will help us to carry on going forward.

We have actually a plan to do more with the transcripts that we have generated from these sessions. We may indeed be able to pull together a very speedy book that sums up all of the conversations we've had here, but we do need funding for that to happen. When you exit the webinar, you will find an exit poll and it would really be helpful if you fill that out, that helps us plan our programming. The next webinar in the series is next Monday at 230 P. M. Eastern when we'll have Cynthia Lazaroff and David Barash talking about nuclear deterrence and mutually assured destruction, which is appropriately known as MAD, mad. So anyway, thank you all very much. Thank you Indi for being with us now, it's past 01:00 a.m. Colombo time. You're heroic so. Thank you very much. Thank you, Phyllis Bennis and Richard. I'll see you see you on Monday.

Richard Falk (01:17:38):

Great. Thank you.

Speakers for the Session

Helena Cobban

Prof. Richard Falk

Phyllis Bennis

Indi Samarajiva

Support Just World Educational

JWE has a golden opportunity to make a difference in this country...

Stay in touch! Sign up for our newsletter: