by Richard Falk

This post is an edited text of Remarks on 30 June 2021 given by Richard Falk at theBook Launch of Timothy Brennan’s PLACES OF MIND: A LIFE OF EDWARD SAID (2021), an event hosted by the Cambridge Centre of Palestinian Studies, moderated by its director, Dr. Makram Khoury-Machool. Also participating in the discussion of Professor Brennan’s book Prof. As’ad Abu Khali and Dr. Kamal Khalef Al-Tawll.

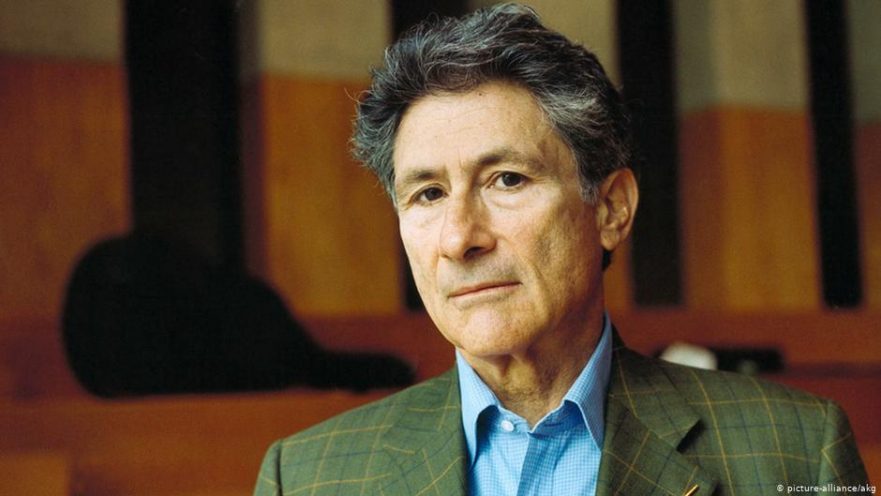

I am honored to take part in this event celebrating the publication of Timothy Brennan’s extraordinary biography of Edward Said. This gathering also provides an occasion for considering once more Edward’s powerful legacy as a creative and progressive icon, someone with a global reach, possessed of as passionate and challenging an ethical, cultural, and political conscience as I have ever had the good fortune to experience. I understand from Makram that my role tonight is to set the stage for the featured performer, somewhat similar to the warmup given to the audience at a rock concert by an obscure local pop group before the acclaimed international star makes his or her dramatic appearance. As I mentioned to Makram, I have two qualifications to be a speaker tonight: I once played tennis with Edward on Cambridge’s exquisite grass courts several decades ago, and more to the point, we were both often embattled due to supporting the struggle of the Palestinian people for a just and sustainable peace.

Edward more than anyone else on the American scene exemplified what we understand to be a ‘public intellectual’ in the late 20th and early 21st century, that is after this presence had been epitomized by the life of Jean-Paul Sartre. Such a role presupposes a degree of democratic governance within sovereign space that tolerates, even if only barely and reluctantly, ideas and critiques that challenge the most fundamental behavioral tropes of the state, captured in spirit by the slogan ‘talking truth to power,’ which is somewhat less activist than Mario Savio’s slogan that embodied the spirit of the 1960s: ‘put your body up against the machine.’

One of the many achievements of Brennan’s book is to grapple with the complexity and contradictory character of Said, who as a friend and colleague was at once engaging, paradoxical, theatrical, seductive, critical, provocative, who could be on occasion defensive and even enraged. Such qualities were distinctively expressed by this most gifted individual possessed of a dazzling intelligence, a sparkling sense of humor, and of course, stunning erudition. Edward was continually reenergized by his curiosity about all aspect of life and about the world. More than the few notable academics of my acquaintance with whom he might be compared, in my reckoning Noam Chomsky and Howard Zinn, and on the right, Samuel Huntington, Said alone was both a hero to constituencies of outsiders and a welcome guest among most insiders, and with his paradoxical style on display he was often a commanding presence in both atmospheres. Perhaps, the secret of his personal magnetism and intellectual preeminence was that he was simultaneously a profound thinker and a consummate performer, a combination rarely found to inhabit the same person.

Such was his charm and the imaginative excellence of his academic contributions that Edward was almost even forgiven in Western elite circles for vigorously challenging the Zionist Project and denouncing Israel’s policies and practices. Brennan points out that Said after he declared himself an activist on behalf of Palestinian liberation was on multiple occasions offered jobs at Harvard and elsewhere that would have made his life easier, yet although tempted, he never abandoned the edgy Manhattan atmosphere that he explored as an adolescent, possibly because he wanted to guard against succumbing to the alluring comforts and urbane satisfactions of the more serene academic life style that the Harvard/Cambridge scene offered. In his pre-activist days, he had partaken of such serenity while a graduate student and earlier as an undergraduate at Princeton where he became a participant in the elitest eating club social life. Perhaps, nothing is more vividly revealing of Edward’s love/hate relationship to the establishment in the U.S. than his disgust with the way Middle East Studies were done at Princeton, undoubtedly prefiguring his most famous and influential rebuff to the disguised style of ‘othering’ Arabs and others by way of his book and work on Orientalism. Despite this, Edward took a bemused delight that his two beloved children followed in his footsteps and received their first university degrees at Princeton. Even after their graduation Edward annually came and taught my seminar in international relations once a year, a high point for the students, and for me a lesson in humility tinged with admiration and affection.

As Timothy Brennan is such a warrior of ideas, himself working in the Said tradition of comparative cultural studies, I am not so foolish as to venture comments in this venue on Said’s seminal work in literary and cultural studies, including music. My relations with Edward were during the last 25 years of his life, but it was for me an enriching friendship that centered on several personal connections and of course our shared commitment to and understanding of the Palestinian struggle, and the multiple obstacles that beset it.

I met Edward through his greatest political friend, somewhat of a guru for Edward of Thirdworldism, Eqbal Ahmad. Like Edward, Eqbal was a larger-than-life character who left an indelible impression on many he encountered, partly a result of his stage brilliance as a charismatic speaker before large audiences and partly as a legendary professor at Hampshire College. Eqbal brought to Edward a vivid form of Third World authenticity as well as exceptional warmth and loyalty as a stalwart friend. Beyond this they proudly shared a theatrical and romantic sense of life as performance, excelling in its execution, which characteristically exhibited disciplined passion backed by humane and humanistic worldviews, illuminating humor, and a deep knowledge of their subject-matter.

Yet both men were involuntary refugees of the spirit who never lost altogether their existential sadness, having been deprived of their homelands of childhood by alien forces. Despite their quite different success stories in America they long forgot these deep feelings of political and autobiographical nostalgia. Both men achieved much in their lives, yet died before fulfilling their respective redemptive dreams. Eqbal’s consuming wish of his latter years was to establish a quality university in Pakistan while Edward’s was to experience directly a liberated Palestine.

It was one of the great joys of my life to have been their friend and comrade over many years, somewhat sharing their strivings for societal, political, and personal fulfillment where justice and love flourish and coexist. And always learning from their example of devotion and steadfastness so meaningly fused with their dedication to justice and their appreciation of the precious quality of lives well lived.

Brennan’s book made me feel, despite my great differences of religion, temperament, background, and talent from Edward, that my life was yet in illuminating respects a pale replica of Edward’s illustrious life story, especially with respect to the choices we made in relation to Palestine, choices that crossed several red lines of political propriety.

I hope it is not overly self-indulgent for me to explicate nervously this comparison in the course of bringing these remarks to a close. We both were products of privileged socio-economic backgrounds, both shaped to a significant degree by the vivacities of NYC’s cultural milieu, specifically that of Manhattan, both educated in preparatory schools. We both attended Ivy League universities, and later earned doctorates at Harvard, and we both remained throughout long professional careers within the faculty confines of the Ivy League. We were multiply linked to Princeton University, and happened to write our most enduring books while visiting The Stanford Center for Advanced Study of the Behavioral Sciences, and finally, and perhaps most relevantly, we both endured defamation and threats because of our outspoken engagement with pro-Palestinian activism.

There were also some manifest differences, none starker than Edward as an ambivalent upper class Christian and me as a nominal middle class Jew, yet surprisingly not very relevant. Of course, Edward’s birth and experience of consciousness in Jerusalem and his Palestinian identity created for him a more natural vector for his political activism.

Brennan brilliantly shows how Said’s oppositional sensibility pervaded all that he did, including eventually including even his relationship to the Palestinian political establishment in Ramallah. My somewhat similar oppositional sensibility remains somewhat more mysterious, but like Edward involves the frustrations and satisfactions of a resolve to swim against the current.

And finally, I think as the years go by Edward Said’s life becomes more and more fused with his texts to form a seamless whole, and no one has done more to bring this confluence to our sense of Edward and his work than Timothy Brennan, whose presentation I now look forward to experiencing in this oral form different from the valuable experience of reading his book.