by Yousef AlJamal

This following piece, by Palestinian rights activist Yousef Aljamal is crossposted from Politics Today

Liberation theology can provide a critical and deep understanding of how politics and religion, and in particular the Catholic Church in Latin America, are interrelated. Liberation theology reveals how religion can be used as a vehicle to justify and translate the religious understanding of politics into concrete action. The message that advocates of liberation theology want to convey is that religion is heavily involved in society, and that the core and essence of its teaching is to advocate on behalf of the oppressed – even if it comes at a cost.

During the 1960s and 1970s, a debate emerged in Latin America that aimed to provide a critique of liberation. In the Latin American context, liberation theology was viewed as a means to strengthen the Church’s presence in public life. It rejected lecturing people from an ivory tower and losing touch with reality under the banner that the church should be separate from politics and that religion should remain pacifist even in cases where oppressed groups are subjected to violence. Concepts such as wisdom and rational knowledge became secondary and complementary to the notion of liberation.

In this context, liberation had three meanings: (1) political liberation, meaning the liberation of oppressed nations; (2) religious liberation, meaning people’s liberation from “sins”; and (3) historical liberation, meaning the liberation of humans as part of the course of history.

The introduction of political liberation to the overall meaning of liberation shifted the discourse and the involvement of the Catholic Church in politics and public life in Latin America. This revolutionary definition of liberation made actors, who had control and influence over the Church for a long time, such as the Vatican and the U.S. administration, feel uncomfortable. Put simply, this new discourse threatened their influence over the Church and its followers.

In 1984, the Vatican issued a document directed at its churches and followers warning them against the theology of liberation, which was advocated by a group associated with the Catholic Church. These attempts didn’t prove successful and they indirectly contributed to strengthening the liberation discourse of the Church and its clergy.

The first meeting of the Catholic liberation clergy was held in Colombia in 1968. In 1972, a year before the military coup in the country, another theology of liberation conference was held in Chile, organized by a group called “Christians for Socialism.” The declared goal of the conference was to encourage human rights against authoritarian regimes and to give meaning to theology by connecting it to society and politics.

The emergence of military dictatorships in Latin America encouraged liberation theology including in Brazil, which was governed by a military dictatorship from 1964 to 1985.

The same applies to Argentina, governed again by a military dictatorship from 1976 to 1983. Today, the Churches of both countries offer strong support to the Palestinian Christians under Israeli occupation and their Kairos Palestine call.

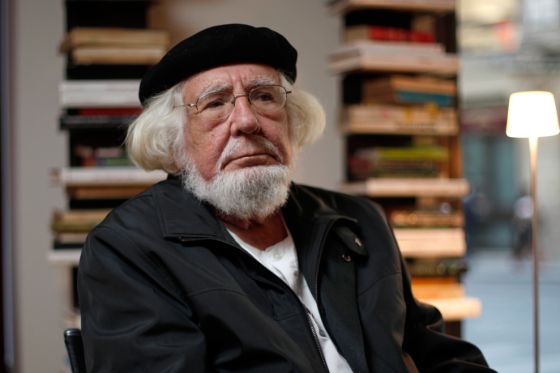

Ernesto Cardenal, a scholar, painter, artist, poet, and political figure, is considered one of the leading names of the theology of liberation in Latin America. He was among a number of priests in Nicaragua who led a revolution against the Somoza family, which governed the country for more than 43 years.

He eventually became the minister of culture after the revolution and engaged in a campaign to spread literacy and culture in the country. Eventually, he resigned following differences over managing the country’s affairs with his comrade and president of Nicaragua, Daniel Ortega.

When Pope St. John Paul II visited Nicaragua in 1983, he openly asked that Cardenal and four other priests who advocated the theology of liberation be removed from governmental posts over their involvement in the revolution and public life.

A famous photo of Pope John Paul and Cardenal shows the former telling the latter that he “must fix [his] affairs with the Church.” A year later, the pope suspended Cardenal because of his role in politics – the order lasted until 2019, when Pope Francis lifted it.

Liberation Theology in the Middle East

In the Middle East, the theology of liberation has gained prominence in countries which suffer from oppression with attempts made to create a movement of Arab theology in Egypt. In Palestine, Hilarion Capucci, a Syrian Roman Catholic priest who was located in Jerusalem, was involved in smuggling weapons to the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) through Jordan and Lebanon. As a result, he was imprisoned in Israel for 3.5 years, during which period he went on hunger strike a number of times. He was eventually released as part of a deal between Israel and the Vatican whereupon he was relocated to Latin America.

Capucci spent the rest of his life in exile in Rome. Ironically, he has supported the Assad government despite the immense suffering, destruction, and displacement it has caused the Syrian people. In 2019, a drama series was produced about Capucci which served as propaganda to whitewash Assad and his regime.

Theodosios (Hanna) of Sebastia is the archbishop of Sebastia, a position he holds under the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate of Jerusalem, and is known for his opposition to Israel’s occupation of the Palestinian Territories. He is seen at nearly every Palestinian national conference or protest.

In late 2019, his political stance almost cost him his life. Theodosios accused Israel of attempting to poison him over his stance against its occupation of Jerusalem after Israeli forces fired a gas canister into his Jerusalem church. He was rushed to hospital and later received treatment in Jordan.

The theology of liberation is an attempt to show that devout Christians around the world see the role of the Church in public life and politics as going beyond feeding the poor and offering them prayers. Its advocates assert that Christianity is about defending the poor and vulnerable, and sacrificing one’s life for this purpose. Christianity, for them, is not simply offering prayers and shying away from public engagement.

Liberation theology emerged in Latin America in the 1960s and 1970s as a result of the many authoritarian governments that appeared in countries such as Nicaragua, Colombia, and Chile. Although it was born in Latin America, liberation theology has spread to other parts of the world and the Middle East. This includes Palestine, which today lies under Israeli occupation and in which Jesus himself was born.

One is compelled to ask the following: what would Jesus do if he returned to Bethlehem and found the city surrounded by Israeli walls and checkpoints? He, too, would rise and reject this reality of subjugation because theology goes beyond education and feeding the needy. It extends to defending the oppressed by all means necessary – be it in Nicaragua or Palestine.