by Karín Aguilar-San Juan and Frank Joyce

co-editors, The People Make the Peace: Lessons from the Vietnam Antiwar Movement

Many people equate Rennie Davis with the Vietnam antiwar movement that he helped to lead. (How influential was that movement? Well, historians have cited recordings of Pres. Richard Nixon querying his staff about the activities and whereabouts of “that Rennie Davis”…) Rennie was included in the iconic “lineup” portrait of the Chicago Seven, a photograph taken by Richard Avedon; and he (or a misrepresentation of him) appeared more recently in Aaron Sorkin’s Oscar-nominated film “Trial of the Chicago 7.”

Last October, Rennie participated in an informative and critical webinar about the Sorkin film organized by the Vietnam Peace Commemoration Committee (screengrab, at right.)

As a pioneering activist and leader in many important developments of the 1960s, Rennie’s work was not limited to opposition to the war. But as the war came to be his focus, he brought immense gifts to mobilizing the movement with creativity and courage.

Rennie’s love for the Vietnamese stayed with him throughout his life. In 2013 he joined a delegation to Viet Nam to join events commemorating the 40th Anniversary of the Paris Peace Agreement, which helped to end the war.

The trip began with a celebratory dinner with Madame Nguyen Thi Binh and her family. (See a photo of the two at that dinner, in the banner above.) Decades earlier Madame Binh–who served as the Foreign Minister of the Provisional Revolutionary Government of the Republic of South Viet Nam–also became an icon, recognized around the world as the face of the Vietnamese revolution. Madame Binh referred to Rennie as her “adopted son.” Understandably so. To his dying day Rennie remained committed to trying to undo the Agent Orange damage inflicted on multiple generations of Vietnamese by the U.S. military’s use of chemical defoliants.

One of the highlights of the 2013 trip was an overnight train ride from Hanoi to the cities of Danang and Ho Chi Minh City (popularly known as Saigon). Rennie shared the small space with Alex Hing and Judy Gumbo: all of them are shown hamming it up in this photo, which no one actually remembers taking!

Following the 2013 trip, Rennie contributed the opening chapter of The People Make the Peace: Lessons from the Vietnam Antiwar Movement, which we edited. One of the many events that featured the book included a three-day-long Vietnam antiwar symposium held at Macalester College and at the East Side Freedom Library in St. Paul, Minnesota in April 2016. Rennie, together with most of the other writers whose chapters are in the book participated on panels and intergenerational dialogues with undergraduate students and local activists.

Following the 2013 trip, Rennie contributed the opening chapter of The People Make the Peace: Lessons from the Vietnam Antiwar Movement, which we edited, and which has also been published in Hanoi, in Vietnamese.

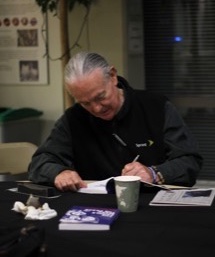

One of the many events that featured the book included a three-day-long Vietnam antiwar symposium held at Macalester College and at the East Side Freedom Library in St. Paul, Minnesota in April 2016. Rennie, together with most of the other writers whose chapters are in the book participated on panels and intergenerational dialogues with undergraduate students and local activists.

Rennie’s appearance at Macalester College in 2016 was actually the second time that he appeared on the campus. The first time had been in August 1970 when he was a featured speaker at the National Student Congress that met there. On that earlier occasion, he encouraged the students to become involved with the People’s Peace Treaty by traveling to South and North Vietnam. Then, once the People’s Peace Treaty had been crafted and signed by students from all three nations, Rennie was one of the movement “elders” who reviewed and polished it for circulation to the public. The People’s Peace Treaty remains one of the most striking accomplishments of the student movement against the Vietnam War.

Rennie’s generosity of spirit and grasp of the value of diverse views within the struggle for justice was one of his great and enduring strengths.

See also, this recent obituary of Rennie Davis from The New York Times.