How on earth did Britain and France “persuade” the world’s other governments to award them colonial-style “mandates” over a large chunk of the Arab world in the immediate aftermath of World War I? How did France, which was awarded the “mandates” over today’s Syria and Lebanon, use its raw power to stamp out what had been a pioneering and politically sophisticated project by Syrians to build a constitutional system for their country? And then, how did France try to erase the whole history of that constitution-building effort and to misrepresent it to the world as some form of raw “Islamist” takeover?

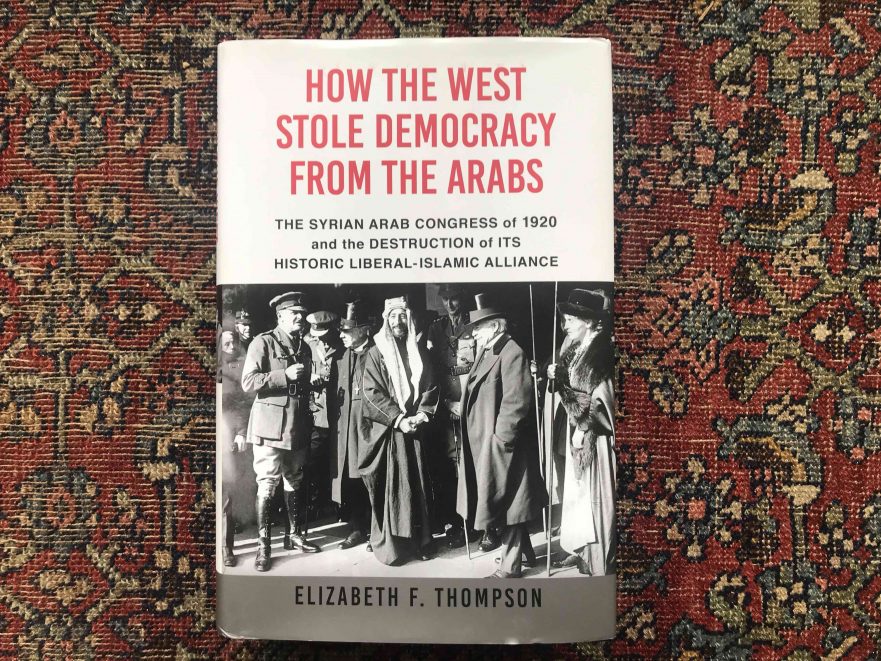

These questions and many more are explored in How the West Stole Democracy from the Arabs: The Syrian Arab Congress of 1920 and the Destruction of its Historic Liberal-Islamic Alliance, a new book from American University historian Elizabeth F. Thompson. On May 21, Dr. Thompson discussed some of the book’s most intriguing findings with noted Middle East specialist William B. Quandt and JWE President Helena Cobban in a 50-minute video conversation that can be viewed here.

Thompson said she had been motivated to start the research on this topic in Summer 2013, after the Egyptian Army brutally ousted the country’s elected President, Mohamed Morsi, crushing the Muslim Brotherhood-led popular movement that had supported him. She said she hoped that some of the records of the short-lived Syrian Arab Congress that had started its work in Damascus in March 1920 could prove useful for pro-democracy reformers working in Syria and throughout the Arab world.

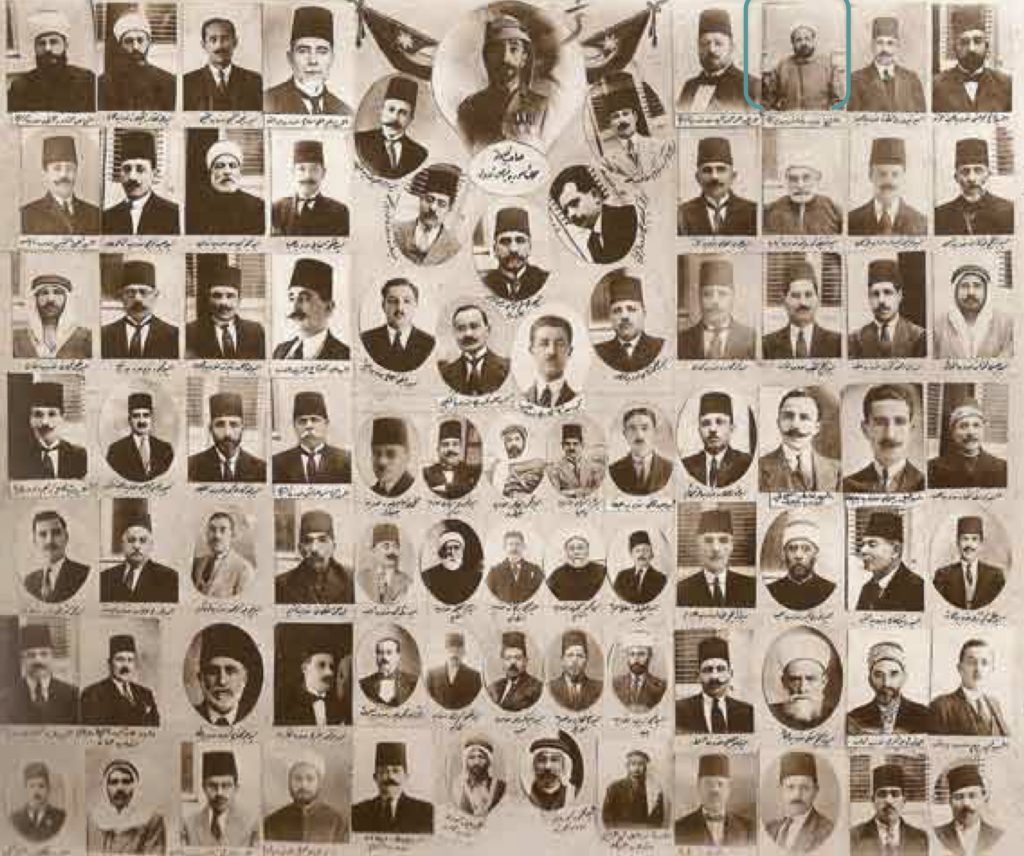

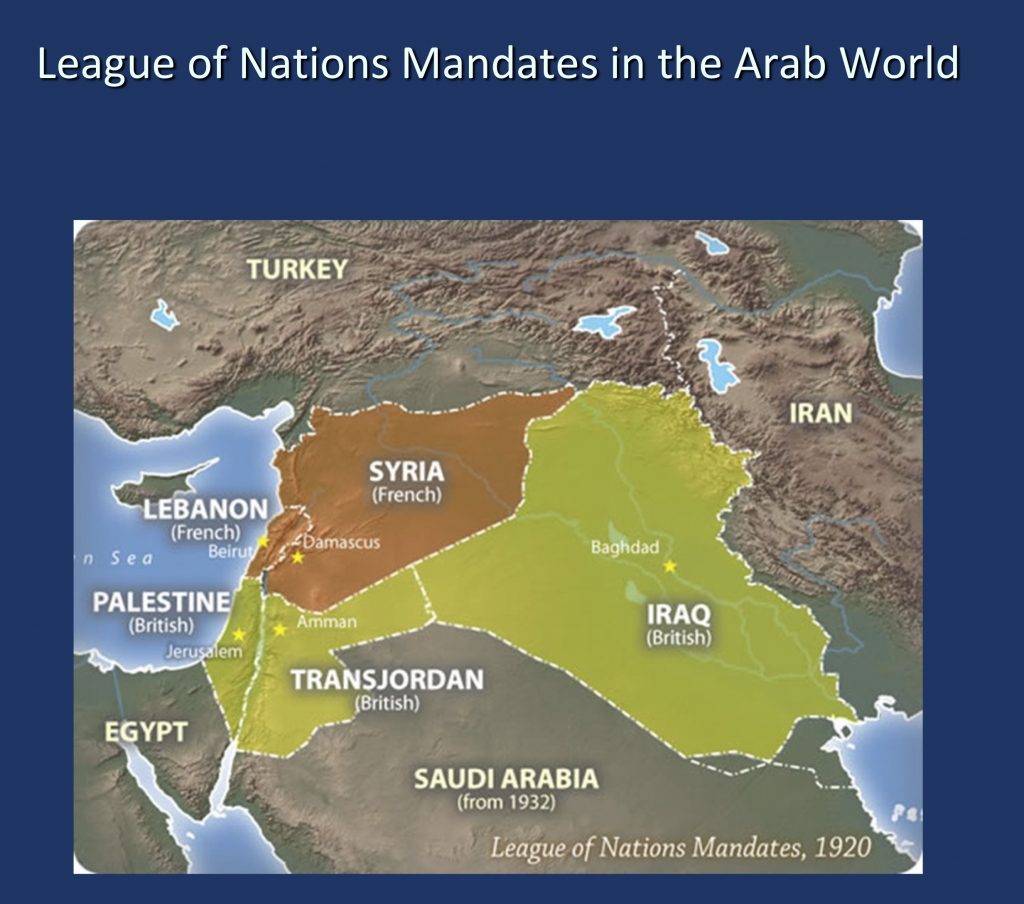

Back in 1920, as she noted, the Syrians still considered that their country included everything that now is known as Syria, Jordan, Palestine/Israel, and Lebanon (as well as the current Turkish province of Hatay.) Delegates to the Congress came from all those regions.

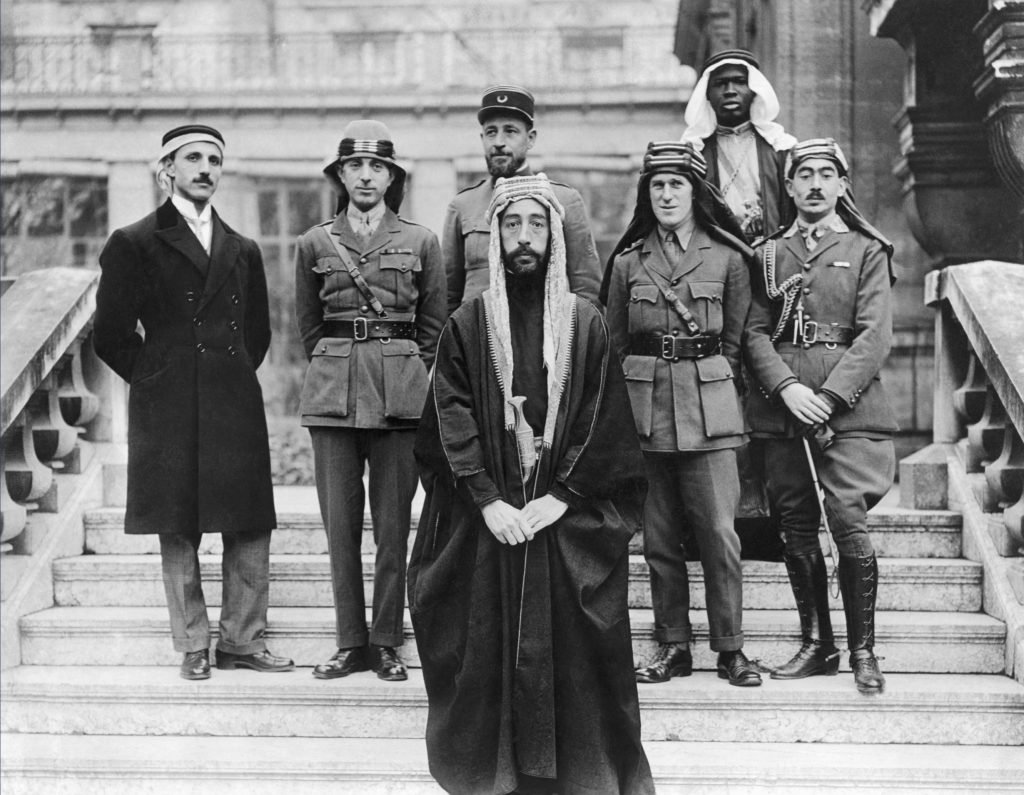

The Congress worked closely with al-Emir (Prince) Faisal, a member of the influential “Hashemi” family from the Hejaz, in today’s Saudi Arabia, who during World War I had worked with the British– primarily, with Col. T. E. Lawrence– to foment a broad Arab uprising in then-Syria against the Germany-allied Ottoman Army. After the Germans and Ottomans were defeated, Faisal continued to work with a broad coalition of leaders from throughout then-Syria to build a governance system for the country in the form of a constitutional monarchy: He would be the monarch but would be subject to the constraints of a formal constitution.

(Faisal is best remembered by many Westerners as the character played by Alec Guinness in the movie “Lawrence of Arabia”. But he actually existed! He was taken by Lawrence to the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, as shown in the archival photo below– Lawrence is shown behind Faisal, to the right.)

In the video conversation, Thompson discussed with Quandt how Faisal had worked with a range of community leaders and thinkers to craft the constitution for the Syrian Arab Kingdom. These Syrians included liberal Islamists, many Christian-Arab thinkers, and some more secular-minded people. But Britain and France were determined to nip this project for accountable self-governance in the bud. They argued that none of those Arabs were “ready” for self-governance and persuaded the League of Nations to adopt the “mandate” system, a barely concealed form of colonialist overlordship, and then divided those “mandates” up between them.

In Palestine, the British used their mandate to give a big boost to the Zionist colonial project. In Syria (and Lebanon), the French were determined to use the same brutal kinds of tactics they had used for decades in Algeria and elsewhere, in order to snuff out the nascent self-governance system and impose France’s diktat there.

Faisal pled with his British friends to be granted his dream of a monarchy– someplace!– and ended up as King of Iraq. Some of the other Syrian nationalists with whom he had worked were imprisoned or killed by the French. Others escaped to other Arab countries.

In the video conversation, Thompson and Quandt discussed at some length the trajectory taken by one key member of the group that had drafted the 1920 Constitution, Sheikh Rashid Rida, a liberal-Islamist writer and thinker born in today’s Lebanon. He ended up in Egypt. Deeply angered by how the Western governments had betrayed his hopes for constitutionalism, he later became a key inspiration for Hassan al-Banna, the founder of the Muslim Brotherhood.

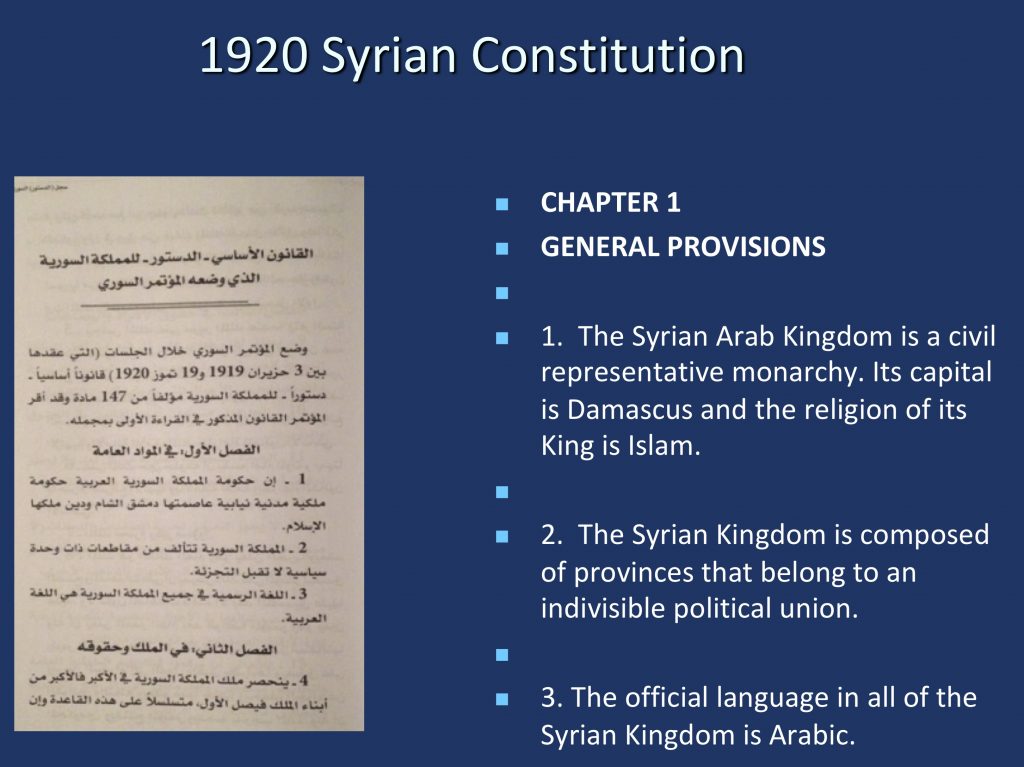

But what became of the 1920 Constitution itself? For Thompson, this was a crucial riddle to be solved, as copies were extremely hard to find. Finally, after a lengthy search in archives in France, Britain, Geneva, Beirut, Washington DC, and elsewhere– as described in the book and the video conversation– she was able to lay her hands on what she believed was an authentic early copy of it. In the first of its 148 articles, it stated that:

The Syrian Arab Kingdom is a civil representative monarchy. Its capital is Damascus and the religion of its King is Islam.

She was amazed. When French writers had described the 1920 Constitution, they had nearly always written that it stated that the religion of the state was Islam– a very different matter.

In the Acknowledgements in her book, Thompson expresses her thanks first and foremost to “the Syrians who have generously shared with me their research and the documents and photographs they have collected.” In the video conversation, she noted she had received numerous expressions of appreciation from historians and other intellectuals in Syria and other parts of the Arab world.

In our recent “Commonsense on Syria” project, we were happy to be able to present, in our inaugural webinar, a discussion of the history and society of Syria that went back to the time in which Syria finally won its independence from France, in 1946, featuring panelists Joshua Landis and Peter Ford. Now, we’re pleased we can add this other valuable video to our Syria Resource Center. We can thereby present an even richer picture of Syria’s history in the twentieth century– including showing in greater depth the degree of the harm that the “West” inflicted on Syria’s people then.

Both the book and the video provide some thought-provoking ideas that might help the work of the current Syrian Constitutional Committee, which held a first, indecisive session in Geneva back in October 2019 (though most likely, no-one today is proposing anything like a constitutional monarchy?) We hope you can enjoy this latest addition to our video library! Oh, and please go out and buy Thompson’s book!

The images presented in the text here are shared courtesy of Elizabeth F. Thompson.