Our board member Alice Rothchild, a veteran health and rights activist, recently made her first visit to Jordan, traveling as part of a small delegation. We are delighted to publish this recent blog-post from her trip, cross-posted from Mondweiss.net. The date on which it was originally drafted was March 24, 2019.

Rothchild’s book, Condition Critical: Life and Death in Israel/Palestine, was published in 2017 by Just World Books.

by Alice Rothchild

Today begins with a ride through Amman (I have not remotely figured out the “circles” and hills and the travel brain fog seems denser today). Perhaps because I was awakened by the muezzin at 4:30 am, not the melodious kind, but more like a blaring announcement at a mall. In turns out the minaret is located right next to the Caravan Hotel, perhaps directly aimed at my eardrum. Pity I do not pray, I certainly would have leaped out of bed. The Turkish coffee arrives with cardamon as we wait for our ride and I am moderately revived.

The sky is cloudy with the threat of cool rain when Careem, (Amman’s answer to Uber), pulls up and we are off to Nuzha Camp in North Amman. The car has that familiar smell of cigarette smoke and perfume. We fly past tall cream colored office buildings, six story apartment buildings, glitzy hotels, palms, and pointy Cypress trees. There is some construction and the usual assortment of Popeyes, Burger Kings, and the local Jo Petrol. The street garbage and litter is minimal and the traffic can only be described as positively civilized.

The neighborhoods tend towards poorer as we reach the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA) facility, a sprawling white building with light blue trim, cheerful graffiti on the outside walls, and kids everywhere. But no guns/barbed wire/ bullet holes. (My previous experience with refugee camps has been in the West Bank and Gaza, FYI). This really makes a difference, needless to say. We meet with Julia McCahey, a cheerful Australian who works in the Health Department at UNRWA headquarters, other staff, and Dr. Akihiro Seita, the health director. He speaks softly, quickly, but with tremendous authority and knowledge, punctuated by a quick, self-deprecating laugh that I suspect is the key to his equanimity.

We talk about the recent UNRWA Trumpian budget cuts of $500 million out of a total budget of $1.2 billion per year, the subsequent need to cut expenditures while protecting both the core supports and the Emergency Appeal (EA) for the West Bank and Gaza (especially food support for Gaza). Among EA-supported activities, the highest priority was given to the food support to one million Palestine refugees in Gaza. In order to preserve such life-saving support to Palestinian refugees, UNRWA had to make a very difficult choice, downgrading other EA-supported activities like community mental health and mobile clinics even though they were important activities. UNRWA was able to save $80-90 million and the Gulf States coughed up $200 million. Ultimately UNRWA came out even and no health center closed. This time.

But challenges obviously remain. Of note, the infrastructure in the refugee camps is primarily the responsibility of the Jordanian government; however, UNRWA is responsible for improving roads, pathways, drainage, as well as the garbage collection services which are all vulnerable to budget cuts.

Dr. Seita explains that it is hard to recruit doctors and hard to retain them, medicine is expensive. UNRWA usually orders medication 15 months in advance but last year could only afford a 12 month supply and there are now “stock outs”. So there has been more sympathy for the UN. “There was no Plan B,” they had to make it work.

In Jordan, 2.2 million Palestinian refugees are registered with UNRWA, most have Jordanian nationality and are included in the social and economic life of the country. The refugees are the center of the work of UNRWA. But even the definition of refugee is complicated here. There are Palestinian refugees from 1948, refugees from 1967 (who are treated differently from ’48 as they theoretically fled from the Jordanian controlled West Bank to the country of Jordan and are thus internally displaced persons).

There are Palestinians who were made refugees (for a second time) from Syria (17,000), Iraq, (numbers are hard to find). Of note, the Palestinians arrived in Iraq in 1948, 1967, (from Palestine) and 1991 (from Kuwait). With the 2003 Gulf War, several hundred fled to Jordan. I am told that those with money were welcomed but the reception was mostly hostile and the population desperate. In 2011, the government estimated that 450,000 – 500,000 Iraqis live in Jordan, although only 31,000 of these Iraqis are registered with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Many were stranded in the no-man’s land between Iraq and Jordan or detained in the Al-Ruwaished Refugee Camp, administered by UNHCR along with Iranian Kurds, Somalis, and Sudanese. Under the Baathist regime, Palestinians were not registered with UNRWA, but had governmental services, health, education, and the right to work. In Jordan they appear to have nothing but their own determination, connections, and the kindness of churches and NGOs.If you are not confused enough at this point, there are some 158,000+ registered refugees from Gaza who are officially called “ex-Gazans,” who fled from Gaza to Jordan in 1967. “According to UNRWA ‘ex-Gazans lack legal status in Jordan and are denied many of the basic services and rights afforded to pre-67 refugees, including access to state schools, government employment, and healthcare.’” Much like Lebanon, without a national ID they are unable to get work licenses in professions including law, engineering, medicine, nursing, pharmaceuticals and journalism. They face further legal and bureaucratic obstacles and cannot become taxi or bus drivers, cannot purchase land or buildings, and cannot set up businesses outside the camp. They are temporary residents with a passport which must be renewed every other year and is often prohibitively expensive. They cannot work in the public sector and can only work in the private sector with security approval which is hard to get. Essentially they are treated like foreign workers. Most work in agriculture, crafts, or vocational jobs like carpentry and black smithing, without social security or health and safety requirements. I would like to note that these restrictive policies violate Jordan’s international and regional obligations as well as international law pertaining to human, economic, social, cultural civil and political rights. Without security approval for a passport, they cannot even legally get married.

Whatever their designation, all these Palestinian refugee groups have a right to UNRWA services. In contrast to other countries, ’48 Palestinians in Jordan can get citizenship and medical and health care benefits. If an ex-Gazan tries to get health care beyond what UNRWA can provide, the cost often triples.

UNRWA is tasked with providing basic primary care and has contacts with Jordanian hospitals for tertiary care and specialty care and provides some reimbursement for that care. Primary care is defined as maternal and child care, dentistry, gynecology, HIV, and internal medicine. Most of the services are for women and children. The centers are open six days per week, eight hours per day and each doctor sees 100-150 patients per day. (Do the math.) The average visits lasts four minutes. UNRWA is working on decreasing “over use” around hypertension, diabetes, and cigarette use through better prevention and screening.

Since 2011, mental health and psycho-social services have been incorporated into primary care. As we question further, this seems to involve brief screenings and referrals to psychiatrists but the numbers of mental health workers in Jordan is relatively quite low (big problem). In 2011, for instance, there were 16 psychiatrists in the Ministry of Health and a total of 61 in all of Jordan

Impressively, each Palestinian presents a refugee card for an appointment, there is a comprehensive computerized medical record, and then care is provided. Of the 2.2 million Palestinian refugees, only the 30,000 most vulnerable live in the camps, the rest live nearby. UNRWA tries to employ Palestinian refugees and 90% of their staff is from Jordan. The care is organized around family health teams, where an entire family consistently sees an entire team of providers who presumably get to know the family closely.We meet with Dr. Rashad who is responsible for north and south Amman and later we meet with the head educational officer. We are told that of the 2.2 million Palestinians in 2018, UNRWA serves 800,000 clients. There are 26 health centers located in Irbid, north and south Amman, and Zarqa. Since 1949 UNRWA health centers have provided preventative and curative care with three major projects:

- Mother: This includes preconceptual care, a minimum of four prenatal visits per pregnancy, postpartum care, and family planning. In Jordan this service cannot legally be provided to an unmarried woman. Depending on risk level, the pregnant woman is followed by a midwife, a family doctor, or an obstetrician. Over the past ten years birth rates have dropped significantly. Contraception is free.

- Child: From birth to five years, children have routine screening, vaccinations, monitoring of milestones, vitamins, and dental care. At five, the child enters school where the school health team provides follow up through 10th They check hearing, vision, vaccinations, and provide dental care. After 10th grade, the teenager is referred to the general clinic

- Noninfectious chronic disease (NCD): Patients receive diagnoses and treatment per guidelines, mostly for hypertension and diabetes, plus dental care. UNRWA serves 80,000 hypertension and diabetes patients in Jordan.

Dr. Rashad informs us that there have been reforms since 2010 including an electronic medical record, an appointment and cueing system, and the family health team approach. The team consists of two doctors, then nurses, and other professionals. Pharmacy, labs, dentistry are not on teams. Since 2017 they have started integrating mental health into the primary care with training from the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Ministry of Health. There is a two week training for screening, and tools, and medications for anxiety and depression. The provider then can refer to the Ministry of Health. There are some psychosocial support groups with trained nurses. It is not clear to me if there is any long term “talk therapy” or if this is all mostly drug oriented.

Each mother and child has a comprehensive health handbook that includes all relevant health information that will soon be available on their smart phones, including appointment reminders.

UNRWA provides educational programs for patients 40 and above, screening for diabetes and hypertension, (endemic in the region), and younger if there are risk factors like a positive family history or obesity.

Before e-health was rolled out, doctors saw 100-150 patients in 6 hours. That number has dropped to (the still way to high) 72-75, but with austerity it is up to 87. (Thank you Mr. Trump.) Nurses do some of the work, but the care is still very doctor oriented. Patients’ electronic files are not shared with the Ministry of Health as they use different data systems.

We learn that mental health and mental illness are very culturally stigmatized, but bringing it into the realm of primary care is providing an opportunity to approach this significant issue. There is no screening for sexually transmitted infections or HIV, but if the provider has suspicions, they may screen for gender-based violence. Addiction care comes under psychosocial care and is referred for treatment.

UNRWA buys drugs from the WHO essential medications list, but last year the pharmacies started having stock outs, for reasons related to international donors, testing standards, etc.

Next we meet the head officer from the Educational Department. He is in charge of the North Amman area. UNRWA runs grades one to ten with the belief that all children have a right to a quality education There are 120,000 studying in Jordan, with 32,300 students in North Amman, 1,000 teachers, 39 schools with double shifts of teachers and students (7 am-12, 12pm – 4:30). Recently grades one to three have become coeducational, overcoming some cultural barriers.

UNRWA follows the curriculum of the Ministry of Education. Some schools are small rented spaces, others large buildings built to be schools with playgrounds. There are 50 students per class and one teacher. Special needs students are included, but not all schools are fully equipped to manage their needs. There is continued teacher training and quality assurance. The teachers do not receive year-long contracts but are paid a day rate. The students generally outperform students in the Ministry of Health schools which is impressive, but probably a low bar.

Post-graduation, depending on students’ scores, they go to vocational schools, secondary governmental schools, or (expensive) private schools. Good scores lead to university training which is highly competitive and expensive, but doesn’t always lead to employment. Rates of unemployment are high in Jordan.

We then tour the clinic (see banner photo at head of this post) and I am pleased with the orderly, clean appearance, the respect for privacy (we are not allowed to take pictures of patients). We see exam rooms, the pharmacy, a dental clinic, a lab. There are a lot of engaging educational posters on the walls. The C-Section rate is reported around 66%, partly doctor preference, partly patient demand. There is not that feeling of chaos and depression I often feel in UNRWA clinics in the Occupied Palestinian Territories.

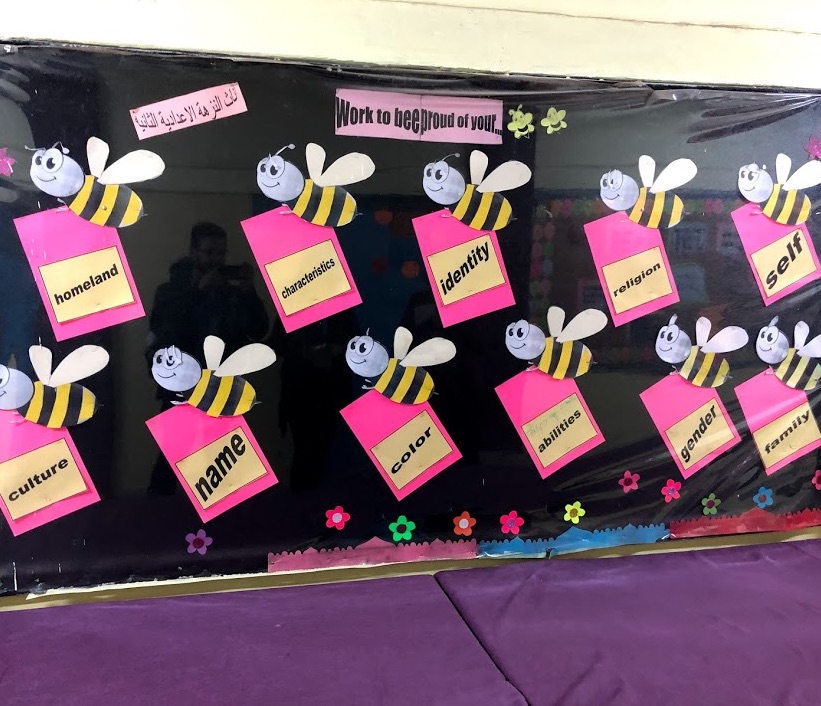

We then tour the Nuzha School compound and I am so impressed with Nadia Musa, the energetic creative principle, hobbling around on a broken foot in a cast. The school is for grades one to six with 700 students and 25 teachers, built in 1969. There are 49 to 51 kids per class, all of the teachers are from the camp. The teachers do a great deal of group work, focus on different learning styles, and do a lot with very little. The classrooms are lively, decorated, the halls are filled with inspirational displays. “It’s not our differences that divide us. It’s our inability to recognize and accept the differences.” “Together we can reach the stars.” “Work to bee proud of…” then a swarm of bees, “homeland, identity, gender, family…” Nadia helped build a community garden out of recycled materials; there are music classes – kids share instruments, two traffic cops (military men in black) appear to talk to the students about road safety. We see a learning center for children with disabilities and a theater with rows of chairs for student performances and community celebrations. One room has a puppet theater.

When we peek into a few classrooms, children are sitting at high desks that are placed on steps, amphitheater style. There are no bullet holes in the windows, and the atmosphere is generally one of infectious enthusiasm. One girl asks: “Is America beautiful?”

We return to talk with Dr. Seita before he dashes off to Istanbul. When comparing UNRWA schools, he says Nuzha was upgraded recently, is less busy and smaller than the Gaza Camp. He stresses that we tell the world that UNRWA does critical work in health care and education in particular. Food is no longer distributed in favor of cash. UNRWA is also responsible for water and sewer infrastructure. But the funding has not kept up with the population growth. Patient expectations are higher, they do not understand why there are not specialists and sophisticated equipment, why ultrasound is only used in high risk pregnancies. In addition, host countries’ health sectors have been getting better as well. UNRWA’s task is basic primary care and the provision of medications on the WHO essential medication list.

In terms of mental health, he states that according to WHO, primary care can manage 70% of the issues when mental health, (ie. the WHO Mental Health GAP Action Program mhGAP), is appropriately and extensively introduced. (I wonder how this happens in the four minute visit). High risk for mental illness includes the Great March of Return, postpartum state, and out of control diabetes. These factors result in more screening, diagnosis and medications such as fluoxetine (Prosac). More serious problems go to the psychiatrists and group sessions.

Violence prevention is still very passive, though domestic violence is common. Plans involve de-escalation training methods in schools for body and mind, (such as deep breathing), and gender based violence teams. For rape victims, there are no emergency services; there is a tremendous amount of family shame, no privacy, and fear of retaliation. Victims sometimes go to governmental hospitals. If a woman is pregnant outside of marriage, she is reported to the Ministry of Health for her own protection and for the protection of the medical staff taking care of her. (Staff have been attacked and there are fears of honor killings). A baby cannot be registered without an identified father.