Video and Text Transcript

Transcript of the video:

(Please note that this version of the transcript has not been finally edited. Fine-tuning the edit is taking longer than we thought. Also, the times given in this transcript are fairly closely tuned to the 76-minute version of the video; but they may be off by up to a minute.)

Helena Cobban (00:09):

Welcome, everybody. I'm Helena Cobban. I'm the President of Just World Educational and this is the sixth of our eight webinars in the series on “Ukraine Crisis: Building a just and peaceful world. My co-host is Richard Folk and our excellent project manager, Amelle Zeroug is in the background. We're lucky today on Monday, March 21 to have with us two guests with extremely deep knowledge and understanding of Russian-Ukrainian and Russian-American relations, both of whom have been doing some very constructive writing and speaking on Ukraine Related issues over the past few weeks.

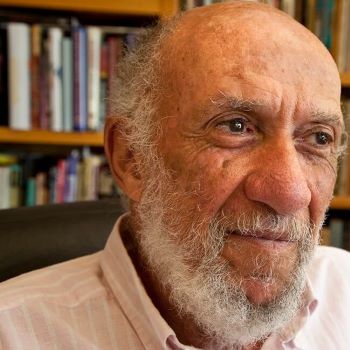

They are Ray McGovern, a fluent Russian speaker who for 27 years was a CIA analyst on Russia. Ray has spent more recent decades as an activist against the excesses of the US intelligence agencies and the warmongering of the US corporate media. In early 2003, he was a founder of the group Veteran Intelligence Professionals for Sanity, which exposed how the George W. Bush administration was falsifying intelligence in a bid to justify war on Iraq. He has long led a Speaking Truth to Power ministry for the Ecumenical Church of the Savior here in City, Washington. Great to have you here, Ray.

Ray McGovern (03:01):

Thank you, Helena.

Helena Cobban (03:04):

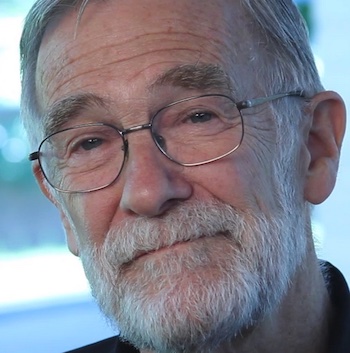

And we have Anatol Lieven who is a senior research fellow on Russia and Europe at the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft. From 1985 to 1998, Anatol worked as a journalist in the former Soviet Union, East Europe and South Asia, covering the wars in Afghanistan, Chechnya and the Southern Caucasus. He has authored numerous books on Russia and its neighbors,including “Ukraine and Russia: A Fraternal Rivalry,” which came out in 1999. His latest book, “Climate Change and the Nation State,” was published in March 2020-- and actually it has great relevance to the topic we'll be talking about today.

Good to see you, Anatol!

Anatol Lieven (03:51):

Thank you for inviting me.

Helena Cobban (03:54):

My co host here is Richard Falk, who I hope needs no introduction. We are both much looking forward to bringing you both into the core issue of how this terrible conflict can be ended on a constructive and sustainable basis. So now let me hand it over to you, Richard.

Richard Falk (04:22):

I just want to echo what you have said by way of introduction. It's a pleasure to have as our guests two of the most influential, articulate, and trustworthy commentators on the issues raised by the Ukraine crisis. I think at a critical point where it's very confusing as to what the leaders of the US and Russia really are giving priority to and whether a viable piece can be established before the economic, ecological, and political adverse repercussions will engulf the whole spectrum of global policy issues. So we meet at a critical time, and I look forward to our discussion.

Helena Cobban (05:35):

Today's webinar is the 6th of a planned eight sessions. Our earlier sessions, involving an array of very well qualified and thought provoking guests, were all excellent. You can access the videos, audios, and transcripts of those sessions and a lot more information about this project at our website, www.Justworldeducational.org. The video of today's session will be uploaded there soon. Today's conversation will be fairly free flowing and is projected to last roughly 45 minutes. After that, there'll be a chance for questions from the attendees, which we ask you to put into the Q and A box. Also, my colleague Amelle Zeroug is behind the scenes here, and if you have technical questions, please address them to Amelle Zeroug in the chat box. Finally, in these emotionally taxing times, we ask everyone for civility from all attendees, both in the chat box and also, if you're invited, on air there, too. So first, I'll come to you, Anatol Lieven. You have done some really fascinating writing over the past few weeks, and last Friday, you had an article titled “Ukraine Has Already Won.” I wonder if you could outline the shape of the piece you envisaged in that article and assess whether views such as yours are actually whether they have traction or they're gaining traction here in Washington, DC.

Anatol Lieven (07:08):

Thank you so much. Well, my argument in that article was that the Russian invasion of Ukraine was clearly predicated on the belief that Ukraine is not really a nation, that the Ukrainian defense would collapse easily, and that Russia would be able to take over large parts of Ukraine with very little fighting. In particular, it was based on the belief that Russian and Russian speaking people in Eastern and Southern Ukraine would basically welcome the Russian invasion. Now, all of those premises have been proved to be false. And in many ways, I think what this war has demonstrated is something that was not necessarily believed before, even perhaps by many Ukrainians and others in the world, and not just in Russia. But I mean, it really has proved that Ukraine is an independent nation, and I think in the process, it has completely defeated any Russian hope of subjugating the whole of Ukraine and turning Ukraine into a client state. I don't think that that is in any way a viable Russian agenda anymore. And it seems to me that actually the Russian government has also abandoned that because of the strength and unity of the Ukrainian resistance, and therefore that Russia's aims are now more limited.

And secondly, that even if we have a treaty of neutrality, which, by the way, the President of Ukraine, Volodymyr Zelensky, has now said is possible, if only because NATO clearly won't fight to defend Ukraine. So the idea of NATO membership is absurd. But I think what has been demonstrated is that a treaty of neutrality would not prevent Ukraine from moving towards the west and developing as a democracy and a successful economy because of what the Ukrainians have proved about themselves in this war. Now, of course, one can't rely on that, whether this unity will last after the war, whether Ukraine would be capable of the necessary reforms. But I think the point is that most of Ukraine, barring obviously Crimea and the disputed area of the Donbas, is now, in fact, once the war is over, safe as an independent country and can seek a compromise peace on that basis.

Helena Cobban (09:50):

Right. Well, I'll come back to you maybe a little bit later about the shape of the peace you envisaged in that article and to assess whether views such as yours are gaining traction in Washington. I'll come back to you on that later. But first, I wanted to ask Ray McGovern to give your assessment of whether Washington is likely to opt for a speedy diplomatic outcome or whether the hawks who want a long, grinding war seem to be in charge in Washington. And maybe what people in the peace movement can do about this.

Ray McGovern (10:26):

In a word, Helena, the hawks are clearly in charge. They are challenging Biden himself to be more assertive and to be more risky in terms of risking more with nuclear equipped Russia. I would ascribe to your appeal for civility. I need to appeal for some understanding of my humility. I've been dead wrong. It doesn't matter if you focus on the Soviet Union in Russia for half a century. It turns out when you say Putin would never be stupid enough to invade Ukraine, you could be wrong. And I was. And so I want to start out on that humble note. I remember hearing once that if you start out showing your humility, well, then you got it made. You can fake that. You can fake anything. Okay, so what's the story here? I was wrong. I wasn't alone. But misery loves company. It doesn't do much for me. What happened? Well, no one seems to acknowledge this, and maybe it comes from my early decades watching Sino-Soviet relations and thinking at the time that these two countries would hate each other forever. Wrong about that, too. More enlightened leadership came in, and before you know it, we have what both countries describe as a strategic relationship that exceeds a traditional treaty.

There is no limit to the cooperation, according to both presidents. What does that mean? Well, I thought it's really neat rhetoric. When push comes to shove, they're going to follow their own strategic interests, and they're not going to get involved in NATO and on part or out there in the South China Sea. I was wrong. The Chinese have decided to become involved in the NATO question, and I think it's partly because a year ago, NATO decided to get involved in the Chinese question. The North Atlantic Treaty Organization was going to go against China. That's what they said. That's, what's his name, [NATO Secretary-General] Jens Stoltenberg said, what we have here is a situation where it's unique in my experience, and that is that we have these two countries, China and Russia. They're so close that it's hard for me to believe. Now, how did this come about? Well, almost exactly a year ago, Tony Blinken and Jake Sullivan met with the Chinese in Anchorage and adopted the attitude of British imperialists, talked down to them, and the Chinese said, you're not qualified to talk down to us. We've had enough of that British type of stuff, enough of that Japanese type stuff.

Don't even try it. Okay. Whoa. Next thing you know, Biden is going to meet with Putin. Now, what does Biden say on June 16 before they could drag him onto the plane, he says, I know I probably shouldn't divulge this because it's inappropriate, but Putin has a real problem with the Chinese. He's being squeezed by the Chinese. They have this long border. China is not only going to be the most economic power in the world, but military power as well. The Russians really are up against it with the Chinese problem. Well, we left a bit of a fly on the wall when Putin turned to his agent, says, “who’s briefing this guy on the situation five decades ago.” Okay? And long story short, Putin and Xi made it their business to tutor Biden. And that's why you end up with incredibly amicable videos and the statements that I mentioned already. Now, that's preliminary here. When Putin journeyed to Beijing for the opening of the Olympics, they discussed a lot of things and they said that. Did Putin mention to Xi that we might invade Ukraine in a little while? My notion is that he certainly did.

Now, I don't think Xi said, “Oh, that's a great idea!” I think what he said was, “Can you wait until the Olympics are over?” And, of course, three days after the Olympics were over, Donetsk, Luhansk were recognized as independent countries, and we had the invasion. So what does this mean? This means that Putin is feeling his oats. Okay? He's got a big brother. He's got enough people that outnumber the people that vote for the US and the UN right now. I mean, 1.4 billion people, a lot in China, India, Pakistan, Brazil, all these people. So what's going to happen? Well, Putin is emboldened. There's a lot of fog of war out there. A lot depends on who is winning on the ground. I don't believe CNN. I don't believe MSNBC. Do I believe the Russians? No, but I look carefully at their statements. And when they warned about a false flag attack, as apparently happened yesterday, an ammonia plant was hit, and luckily the wind was going the right way. So the village next to the ammonia plant was not poisoned. I see that coming, and I see the Russian TV and radio networks are being very harsh, uncommonly.

I haven't seen this in decades and decades. So what we're up against here is a situation where, in my view, the Russian victory is inevitable on the ground that their aim was never to take over the whole Ukraine. Their aim, as Putin explicitly said, was denazification, and that's a major task and demilitarization. Now they have a cauldron. They have hundreds of thousands of troops from Ukraine, many battalions surrounded in Southern Ukraine. That's going to be a matter of time before they clean that place out, and then a lot of those tanks will be free to go up toward Kiev. What's the solution? The solution, in my view, is a ceasefire immediately. No more fooling around with false flag attacks. That thing in the theater in Mariupol, false flag attack read Max Blumenthal today. He's got the final story on that. It was the Nazis that did that. Okay? 300, 400 people didn't matter. So what we need to do is cut through the fog of war. Do I believe the defense spokesman, Major General Igor Konashenkov, more than I believe John Kirby or Jan Psaki? Yes. He has not lied. He's done a lot of work speaking for the Russian military.

So, you know, it's really hard to say that. And of course, I opened myself for all kinds of accusations, but this happened with Russia gate, this happened with Iraq before the war. So I'm used to it. I'm used to being ostracized, and there's very little chance that I will be invited to any of the major media platforms, whether it's cable or TV or radio. So I could speak my mind, just as I did as a CIA analyst when back in the day we were able to speak truth to power without fear or favor. And it's a nice way to live because I don't have to work for anybody and I don't have to do anything except try to tell the truth. That's what I'm doing.

Helena Cobban (19:23):

Thank you, Ray. So, Richard, what's your immediate response or what would you like to say in reaction to what we've heard from Anatol and Ray?

Richard Falk (19:34):

Well, I think we've heard very good starting points for a multi dimensional conversation. I would like to just throw out a couple of things. I was very grateful to Ray for bringing in the geopolitical level of the interaction, because I think that has taken priority over what's good for Ukraine and the Ukrainians, and it's become maybe not an actual, but a virtual proxy war between Russia and the US. That's worth reflecting upon. And then I think it would be useful to get the reactions to, Who is Putin? Is he this rational calculator... and he made a miscalculation? Let's take that for granted that he made a miscalculation with respect to Ukraine, but still he is an informed, normal leader and with rational objectives. Or is he this kind of geopolitical maniac that wants to recreate the old Tsarist Empire, a person that is not mentally stable? And you find both of these images very much present in the discourse. A third question I think would be useful: Does a peace process require a mediator, and if so, what countries or what individuals would qualify for that role? Michael Klare has written recommending Turkey, China and, and what was the third country? And Israel. No wonder I forgot them. They're so implausible as a mediator, but it seems to me that's important. What will make a viable piece, have some chance of becoming a durable piece?

Helena Cobban (22:37):

I guess what I heard from the two presentations was, in a sense, two very different assessments. One, Anatol, you were saying that Ukraine has won, and Ray was saying that Russia is going to absolutely win. And as I understood what you were saying, Anatol, it was more like in a Clausewitzian way that, at the political level, Ukraine has won, whereas maybe Ray was more like hard military on the ground. But however we want to assess victory or defeat, I think all of us in this gathering want the fighting to end ASAP. I see lots of nods. That's good. I mean, if we didn't have nods on that--? But it might be somewhat easier to end the fighting if each side can think that it has something of value to it. You don't want to grind everybody's noses into a defeat. We tried that with Germany after World War One, and as Tom Lehrer notably said, "We taught them a lesson in 1918, and they haven't bothered us since then...", about Germany. So how are we going to get to a very speedy ceasefire that locks into the kind of a negotiation needed to make the cessation of hostilities final and build a sustainable peace? So I guess I'll come back to you, Anatol, first, and then everybody take it from there.

Anatol Lieven (24:33):

Thank you. Well, it seems to me that we may be heading for what's called a mutually hurting stalemate in Ukraine. Russia certainly will make more progress on the ground. It will capture Mariupol in the next few days or so, and probably the whole of the Donbas areas, most of which people forget, were actually held by Ukraine up until now. But I mean, on the other hand, the Russians do appear to be losing very heavy casualties. The Ukrainians have claimed several generals and other senior officers killed. The Russians have admitted some of this, and in other cases, well, they haven't produced the individuals alive to disprove this. It's interesting that the Russians deployed far too few troops for this operation. Now. That's partly, of course, because they completely underestimated the Ukrainians. But it seems that it's also because Putin is very anxious not to use conscripts as far as possible, trying to use professionals. Of course, they're better soldiers, but it does seem also that he is worried about Russian public opinion if large numbers of conscripts end up being killed. Well, that is an argument that the Russians cannot afford to go on losing men at this rate for very long.

I mean, for a while, yes, but not forever. So they have an incentive to stop and negotiate once they have occupied what they regard as enough, A, for their territorial claims and, B, to put pressure on the Ukrainians. The Ukrainians, on the other hand, put up a tremendous fight, but they are also losing heavily. We hear less about that because, frankly, the Western media is very biased in favor of Ukraine. And, of course, also Russia has the will go on doing terrible damage to Ukraine if this war continues, terrible economic damage and also tremendous physical damage and human damage to Ukraine. And while I think that the Ukrainians can now hold most of their main cities because Mariupol has 500,000 people, Kharkiv has one and a half million, Kiev has three and a half million. These are formidable places to capture against a determined opposition. Once the Russians have dug themselves in, it would be very difficult for the Ukrainians to reconquer territory from the Russians. And so you have a situation, I think, already in which, frankly, the Ukrainians are unlikely to get a better deal, five years, ten years down the line than they would get.

Now. Of course, as Ray has suggested, there are people in Washington who have no problem with that because they didn't give a damn about the Ukrainians and how many Ukrainians die. You hear people talking. I was a British journalist in Afghanistan in the 1980s. You hear people in America and Europe now talking about how Afghanistan was such a tremendous victory, support for the Mujahideen.

And the infernal, the gross immorality to say that this was a cheap victory, but, of course, it was cheap in money terms. It wasn't cheap in terms of Afghan lives, a million or so, and the destruction of the Afghan state with consequences. That, of course, came back to hit America terribly ten years later. So I think that, yes, we must really focus on the fact that there is, I think that there are the grounds for a peace agreement now. And what would that consist of? Well, neutrality, as I've said, one, because if Ukraine will not get into NATO and NATO will not fight to defend Ukraine, then, as Zelensky has said, that's obvious, not the dissolution of the Ukrainian armed forces. That's out of the question. But there are suggestions now from the Russian side that this could only involve, it would be folded into neutrality, and it would exclude NATO bases, NATO weapons systems, and missiles that could threaten Russia. So something along the lines of the resolution of the Cuban missile crisis, if you will. Denazification is still a vague one. But perhaps if Russia is anxious to reach an agreement, that could be a statement from the Ukrainian site saying we categorically reject Nazism and all these things.

And then there are suggestions that, as I myself have repeatedly advocated, the Ukrainian side should not seem to bow to Russian pressure on Russian language rights in Ukraine. It should make a free offer on its own to withdraw the laws discriminating against the Russian language, because after all, the Russians and Russian speakers of Ukraine have deserved this by their loyalty and resistance. Now the biggest problem, it seems to me, is the territorial issue. Ukraine would not lose anything by recognizing Russian sovereignty over Crimea because Crimea has been lost for the past eight years. And no expert I know thinks that Ukraine can ever reconnect and no successor regime to Putin's, if such there ever is, will agree to sacred to give up Crimea again. Navalny has said that. He said we need a second referendum in Crimea to confirm its part of Russia. Absolutely, fair enough. But he hasn't said. He has certainly not said that. In fact, he has ruled it out, simply giving Crimea back to Ukraine. But the Ukrainians have suggested that this could be compartmentalized. In other words, kicked into the diplomatic long grass for future negotiations.

What Russia will definitely require, however-- this kind of thing should be part of a peace settlement anyway-- are guarantees that Ukraine won't do what Ukraine very foolishly has been doing for the past couple of years, which is blockading the water supply to Crimea, which was doing terrible damage to Crimea and agriculture and the Crimean economy. One of the reasons why Russia is demanding recognition is to rule that out in future. But obviously a peace agreement would have to have elements saying no military pressure, no military threats, and no economic pressure from either side on this while the negotiating process continues.

The Donbas is a bigger issue because, of course, Russia has recognized the Donbas republics in the entire territory of the two Donbas provinces, but at the start of this war, it only held part of those provinces. That means that either the Ukrainians have to give up more territory or the Russians have to retreat from territory that they've conquered. But there is an elegant way out of this, which is that what could be could be internationally supervised referenda on the whole territory of these provinces, but on a district by district basis. And one would assume that the areas that have been separatists for the past eight years and have been repeatedly shelled, people forget this, and bombarded by the Ukrainians would vote to stay with Russia.

And I think it's a fairly safe assumption that the areas that have recently been attacked by Russia (and of course, many civilians have been killed) would probably vote to stay in Ukraine and so you would have those areas partitioned. Now, in a reasonable world, all of this seems to me actually fairly obvious and negotiable, and it also seems to be the kind of thing which in other circumstances, the west itself would put forward as a solution for a conflict of this kind.

But A, of course, we don't live in a reasonable world, alas. You are working on this. I congratulate you, but we're not there yet. Right. And secondly, of course, the west is hardly a neutral broker in this. And as Ray has said, you have powerful elements in Washington who are perfectly happy to fight to the last Ukrainian in pursuit of American geopolitical agendas of basically, well, obviously overthrowing Putin, but also weakening or destroying Russia in order to isolate China.

So I think the reasonable basis for a settlement is there already. I also think, as I say, that if this war goes on for ten years, the ultimate solution will probably look the same. But whether we can actually bring that about.

Helena Cobban (34:17):

So, Ray, any response to that?

Ray McGovern (34:20):

Yes, I'll try to be brief. We have a very difficult situation in Washington where Biden has very sensibly said no fly zone. And then Pelosi and Schumer invite Zelensky to say, oh, why can't we have a no fly zone? Or why can't we have S-300’s and so forth? What's wrong with that picture? Who's writing Zelensky’s speeches?

Helena Cobban (34:51):

I have to say that Zelensky's appearance did for me bring back when Netanyahu came and spoke to the Congress, undercutting the JCPOA back in 2015, 2016. I mean, there is the question of the separation of powers in this country. Who makes foreign policy anyway? Sorry.

Ray McGovern (25:15):

Well, I'll follow that with another digression. And that is when the Pope came to speak to a joint session of Congress in 2015. What did he say? He said, quote, the main problem today is the blood soaked arms traders, period, end quote. And all those congressmen got up and then they look to see if the latest check from Raytheon was there, maybe it fell out while we were clapping, one from Lockheed, it was giving hypocrisy a bad name. Now, why do I mention that? Because that's at the root of all this thing. There are people that profit here from this tension, profit here from going up to almost war with Russia. And that is what I call the Mickey Mouse, the military industrial, congressional, intelligence, media, academia, think-tank complex. Look at all those institutions. They're all in it together. And I said media, because without the media it doesn't work. Eisenhower himself said, look, the only antidote for the military industrial complex is a well informed citizenry. Now getting back to Ukraine, I don't know who's running the show. So far, Biden has resisted these folks. And then when I saw Chuck Todd yesterday talking to the NATO Secretary General and saying, now, look, about the no fly zone, suppose there was a chemical attack.

Would that change the calculation? Would that change it? Well, that's exactly what Chuck Todd did on the 20th August 2012 to mousetrap Obama into setting a red line, which was violated exactly a year later in Syria when there was that chemical incident outside Ghouta, which was proven to be a false flag attack. What am I saying here? I'm saying the fog of war is really thick on this one. Where do we get our statistics on how many people have been killed on either side? Well, we don't have any accurate statistics, and we ought to recognize that. Why can't we get to the table and just be sensible? Well, I think and the original question there by Richard, is Putin deranged now or is he still a calculating kind that we thought he was? I think it's the latter. But he's got a big brother now. He's got China right behind him. And I think the implications of that have been missed by most Western analysts. So if Putin's got this big guy behind him and he is genuinely concerned about Russian citizens in the Donbas, and he does know what's happened to them. 140 casualties in the Donbas.

How many of those were Ukrainian nationalist guys from the Azov Battalion and so forth? Very few. They were mostly Russian speakers. So I think that Putin is still very calculating, but also a little bit emotional about how he's been unable to protect these people for eight years in the Donbas. So when he talks about denazification, there's no denying that he means that's Mariupol, they're full of the Azov Battalion. So he means to conclude that. And what I'm saying here is that until he cleanses, until there's a real cleansing of neonazis and they're easily identified. I mean, we know the people that did that terrible event in Odessa on May 2, 2014. We know who they are. We have their pictures. So does the KGB successor. So what I'm saying here is that we have to sort of get together and talk about what's real. And Navalny was mentioned. He's not a serious person. He has no following in Russia. He's purely a product of Western propaganda. And that can be proven. When they talk about Putin has used chemical weapons against his own people. Whoa, what does that bring back? There was another guy accused of that.

That was Saddam Hussein. Why are they accusing Putin? They're thinking about Navalny, they're thinking about [Sergei] Skripal, they're thinking about [Alexander] Litvinenko? Give me a break. None of those things bear close scrutiny. And when I hear my good friends repeating them as an indication of why they quote “Detest Putin”, I say to myself, wow, even the best people can be a little bit deranged when it comes to chemicals, biological. So I've said enough. really interested in the rest of the questions.

Helena Cobban (40:16):

Well, I want to come back to the question Richard referred to, and that is really given that Anatol has told us, I think fairly convincingly, that there is a doable negotiated peace at this point and that another ten years of war might destroy Ukraine and completely upend a lot of the rest of the international community, but won’t get any better deal than what you can get now. But how, just technically, what is the avenue through which such a peace can be gotten? Richard had mentioned some of the potential mediators, but how about the role of the United Nations, the OSCE, the BRICS complex, or individual governments like that of China or Turkey or Israel?

Anatol Lieven (41:17):

Well, I think that actually Israel might have the best chance because Israel is more or less trusted or friendly to the three main participants, which are, let's face it, Russia, Ukraine and the United States. That cannot, alas be said of Turkey or of China, the United Nations. I mean, look, 60 years ago under Dag Hammarskjold, the United Nations would have been the obvious institution to step into solve this crisis. But, of course, since the end of the Cold War, the United States has basically made it a program to subjugate the United Nations and turn it into a powerless institution. But the United Nations can certainly help in the form of providing international legitimacy for referenda on the status of the disputed territories and also perhaps to provide genuinely neutral peacekeeping troops and observers, as in other conflicts, to monitor a ceasefire at the end of the war.

Whether the present Secretary General has it in him or has the backing actually, you know, fairly forcefully to promote a peace settlement: that I doubt. He certainly has not done so, so far.

I do have to, however, say that I think that in our criticisms of US policy and certainly recognition of the fact that there are neofascist elements in Ukraine, we should not seem to let Putin too much off the hook here.

The fact of the matter is that he did launch this invasion. The people who said he wanted to protect the Russian speakers and Russians of Eastern and Southern Ukraine are overwhelmingly the civilians who have been killed in this present conflict. And also what Putin is doing at home in terms of repression and driving many people into exile risks undoing all the cultural gains for Russia it has made since the fall of the Soviet Union. Of course, that's been an extremely ambiguous process, as we all know, the looting of Russia and so forth. But nonetheless, it is a terrifying sight to see just how many Russians who should be playing a key part in their country have been, well, first, people in senior positions excluded from Putin's inner circle over the years. And I do think that that is one key reason why he was, I think, clearly very badly informed before launching this war. Apart from the House, in terms of the economic consequences, there are no senior economists or economic officials or financial officials in his inner circle. And both the narrowing of the regime itself. But also if you look at the cultural figures, including even some like the actress Chulpan Khamatova, who were previously pro-Putin, who have now been forced into exile because they've refused to support this war, we do also need to recognize that Russia, Putin is doing terrible damage to Russia by this. And, of course, the economic damage to Russia is colossal. So the onus is also clearly on the Putin regime also to seek a reasonable end to this war.

Helena Cobban (45:23):

So who can persuade him? The way I look at it, I don't pretend to know anything about the balance of forces in Moscow, but I sit here in Washington, DC. I see a lot of like a sort of a battle between the hawks and the relatively reasonable people here in Washington, DC. I suspect something similar is going on in Ukraine. I think Zelensky has made some very important statements, including recognizing that Ukraine will not be part of NATO, and he has continued to talk directly or his people have continued to talk directly to the Russians, which I think is an important aspect of what's happening. So they don't necessarily need a mediator at this point, but probably mediation needs to happen, or at least support for the peace overtures as opposed to support for militarization and all the kind of one-sidedness that goes on here in the NATO countries.

How do we bring home to the publics in our countries, in the NATO countries, the massive costs of the long war? Richard, do you have any ideas on this? Because the public here in the States, and I think even more so when we were talking with Mary Kaldor in London last week, I mean, she just seemed sort of very mobilized on an anti-Putin kind of crusade. Maybe, I'm mis-characterizing her, caricaturing what she said, but she was pretty clear.

Richard Falk (47:12):

I think what Anatol has been stressing can be translated into the domestic political discussion here and should be the economic repercussions so far have been felt at the gas station mainly, and that had some impact. But to understand that this is not just a matter of isolated instances of inflation, but risks a global food crisis, it risks imperiling interests of the US all over the world, and it would result in a sharp downturn at home, including a likely recession of a rather deep and lingering kind. So I think that responsible commentary has a role to play, even though the mainstream media has so far been rather disappointing about pointing out the negative dimensions of the way in which the US has pursued the issue. And I would fault Biden more than Ray does. He has stood up against the no fly zone, but his State of the Union speech to Congress really was inflammatory and didn't have any dimension of seeking a durable peace or looking at the wider costs of the continuing reward. So I think we have to wonder whether the Biden leadership is any more trustworthy in this kind of search for peace than what's going on in Moscow.

Helena Cobban (49:41):

Yeah, great.

Ray McGovern (49:42):

I’d just like to ask a comment or two. The issue of who is advising Biden seems paramount. I have always said since they proved themselves a year ago that it was a junior varsity team that Biden brought in in the foreign policy area. And I think they've distinguished themselves as real losers. What about his economic advisors? I have no more confidence in them. And I think that they have started a ball rolling here with these sanctions and the repercussions that will be worldwide as well as in the United States, that they didn't think through, that maybe they couldn't think through because they're not that smart. And so that's a real issue that's going to be coming up. And with the midterms coming and with the general election in two years, it's going to play into the political situation. Now, I'm Vladimir Putin, right. And I'm looking at all this. I'm on record as saying the United States foreign policy is hostage to domestic political developments in the United States. I've seen that, says Vladimir, I make agreements with the US President, like, for ceasefire in Syria and the Air Force bombs the hell out of Syrians eight days later, even though he and I personally approved the ceasefire.

So what I'm saying here is there's a real large lack of trust and nothing's going to happen anytime soon. And what I'm interested in is stopping the carnage. Okay. Let me just give one small personal example here. I'm a pretty old guy, right? I remember when the Russians invaded Hungary, there was a revolution in Hungary, and they're American, we were all going, “They’re going to throw the Russians out!” No way. Russian tanks came in. What did Radio Free Europe under our Tutelage? What do they do? Resist? Why? Before those Russian tanks? Make sure you fight this thing out and thousands and thousands and thousands of people die. Now, in this case, we learned a lesson. Okay? I was sent out to Munich with the primary purpose of making sure that when the Russians invaded Prague, I and the head of RF Radio Free Europe were convinced that this was inevitable. Okay. When? In August they did, I was able to give them guidance on what else was happening. Were they going to invade Romania? No. And please don't incite the Czechs and the Slovaks to do what we incited the Ukrainians to do. That was a very good job.

I mean, I just felt very proud of being able to play that role. Now, what are we doing? What are we doing in Hungary? What are we doing in Czechoslovakia?

Helena Cobban (52:53):

I'd add to that when George H. W. Bush, in March of 1991 called on the people and army of Iraq to rise against the dictator there, which in the south of Iraq, they did, and they got slaughtered in their tens of thousands. So let's put that into the mix, too. We have some really interesting questions here. Steve is asking who are the key people and groups in the United States on Ukraine policy? Can they be influenced?

Anatol Lieven (53:34):

Well, I think they can be influenced, amongst other things, by the growing threat of a global economic crisis and also how much they care about starvation in other parts of the world. I don't know. But they might well care about food riots and political instability in the Middle East, where key US allies, climate States like Egypt, are critically dependent on Russian and Ukrainian wheat imports, Algeria to Morocco. So, I mean, I think that that might be a real incentive to try to bring this war to an end and lift some of the sanctions.

Helena Cobban (54:20):

Yes. Ray, you have something on this.

Ray McGovern (54:24):

I was going to say a little thing to add, but it's not a little thing at all. It's a quintessential thing. It's global warming. Anatol has written a book about this. We have ten grandchildren. Okay. Now, everyone recognizes, even the director of national intelligence, that this is the real crisis we face and that it requires cooperation among all, not only total government cooperation, but total world cooperation. And what's happening that, as I've described it in my writings, is the mother of all opportunity costs, the mother of all opportunity costs, because the opportunity is not going to be around very many years to degree this kind of strife, this kind of unnecessary killing persists, then over the long term, it will just make it quicker that my grandchildren will meet an untimely end with no fresh air and no water to drink. So this is an opportunity because it should be taken into account. That's why we need a ceasefire right away. That's why we have to kind of tuck in our pride and make sure we make a deal, because the deal, as Anatol has suggested, is ready there to be made. Richard, I'd like to come just like.

Anatol Lieven (55:47):

If I may say. I mean, I've been horrified by the way in which climate change has disappeared. Well, the Secretary General of the UN did actually say today that it would be madness to allow this to drive us back to dependence on fossil fuels as a short term response to this. But that is exactly, of course, what we see happening.

Helena Cobban (56:10):

You're quite right. I want to ask Richard, actually, how he sees international law playing a role in bringing about a just and speedy end to the crisis, because we hear all these calls for Putin to go to the International Criminal Court. Putin is a war criminal. How can we deal with him? So it seems that international law, in the way that it's understood in this country right now, is sort of a barrier. If you're going to threaten people with criminal prosecutions, what's the incentive for them to come to the negotiating table?

Richard Falk (56:56):

Of course, that's true Prudentially. It seems like it works against what we all believe imperative, which is an immediate stopping of the killing, and to ratchet up this personalization of the consequences for Russia, of the war seems to me to be geopolitically dysfunctional at this stage. And I would point out further that international law is from thoughtful people getting a very bad name, because what we're alleging about Russia is what we've done repeatedly around the world. And so one has to distinguish between international law as a normative regulator of behavior, from international law as a geopolitical policy tool used against our antagonists or rivals. And it has no credibility when it's used in this latter way and, in fact, diminishes the whole idea of a normative order. And when Blinking, for instance, talks about a rule-governed world, he makes it clear that the rules are generated in Washington, not in The Hague. And our response to the ICC's investigation of war crimes in Afghanistan is one thing, and it's quite another when we celebrate the investigation of Russia's war crime. So the level of hypocrisy and the failure of the media to at least give some attention so that people can begin to understand that what we're demanding of Russia, we've never adhered to ourselves.

That kind of double standard and really marginalizing not only of international law, but of the UN Charter and of the authority of the international organized society to dictate the rules or to agree upon the rules. And that's what I mean. World order is governed by the discretion of the geopolitical actors. And this was written into the charter by giving the most dangerous countries in the world the veto power that was part of the design of world order. International law was for the weak, not for the strong. So that's why I distinguish between world order, where you acknowledge that an international law which purports like all law to treat equals equally.

Helena Cobban (01:00:28):

Good point. And of course, of the five veto-wielding members of the Security Council, permanent members of P, five three of them are members of NATO. So that is deeply baked into NATO's power in world affairs. So we have a question about the mainstream media in this country from Elizabeth Axtell, who says the mainstream media being what it is, how can Americans know what is true and not true regarding this conflict? Rachel, we come to you quickly and then go to Anatol.

Ray McGovern (01:01:09):

Did you say me first?

Helena Cobban (01:01:11):

Yeah. How can we know what is true? I mean, it's hard.

Ray McGovern (01:01:20):

Well, the deck is stacked against those who would like to know what the truth is. If Condoleeza Rice can go on cable TV and be asked “Invading another country without real cause. Is that a war crime?” “Yes, that's a war crime.” And no one will say, My God, she's condemning herself. It should be brought before the Hague for that, because this is what she and her colleagues did. So what I'm saying here is that the cable TV and even some of the radio media cannot be trusted. So what do we do? I don't know. I've been trying for 20 years to break through. We have a pretty distinguished group of experienced professionals in intelligence and we can't get the time of day. So I go on every show that asks me. I compliment you on this one, but it just baffles the mind that Americans can drink the stuff that they've been given to drink the Kool Aid, I would say, and then not realize what Condoleeza Rice represents. And more. Just to finish with this here, I never heard maybe it's my lack of education, but I never really heard wars of choice.

Ray McGovern (01:02:48):

That's a war of choice. Putin has done a war of choice against Ukraine. Well, the first time I heard about war of choice was Iraq. And that label was extremely correct with respect to Iraq, because Iraq posed no national security danger to the United States of America or Britain. Okay. Now is it different with Putin? Well, I would say that viewed from Putin's perception, food from his location, looking at NATO arms going into Ukraine and populating Ukraine with this kind of armament, even before Ukraine is made a member of NATO, that is a national security threat. And so it's a war of choice, but it's a difference in genus, not just species.

Helena Cobban (01:03:43):

Okay. And Anatol, how do you get your news?

Anatol Lieven (01:03:49):

From the widest range… I suppose the BBC and the Financial Times are my basic sources, but of course, I am very careful to balance them with as much information as I can from people who I trust on the ground and independent voices in the west. I began to be disillusioned with Western media when I was a journalist myself. Certainly what happened over Iraq put several nails in that coffin. So I'm not too surprised by the kind of complete loss of any attempt at objectivity, the total confusion. Who said “comment is free, but facts are sacred”? That has quite simply disappeared from CNN and MSNBC. One expected that of Fox. But as an old Social Democrat myself, I have been very depressed to see institutions which I used to greatly respect, abandoning every standard of what I regard as respectable journalism. It's very difficult. Well, all I can say is we're still better than Russia, but that is not a high bar.

Helena Cobban (01:05:23):

A low bar, yes. So we have a question from Jeremy, is there evidence that the US is pressuring Ukraine against serious negotiations? Are there ways to counteract that pressure either in the US or internationally?

Anatol Lieven (01:05:47):

Well, I haven't seen any direct evidence of pressure. Perhaps Ray is better informed than me on this, but certainly, I mean, if you look at the statements from the Biden administration, they have gone out of their way several times to downplay or dismiss the idea of successful negotiations. So there certainly does not appear to be any strong support for the peace process at present. And given that inevitably Ukraine will have to make certain concessions for peace, and also that Zelensky will face serious opposition from Ukrainian hardliners, we should remember that at the start of the conflict, the commanders of the Azov Battalion called Zelensky a traitor for even agreeing to talk to the Russians and suggesting neutrality. Now they've gone quiet on that because Zelensky, of course, has emerged as a great national hero in the course of the war. But we should not remember that the number of leaders, even great national heroes, who have been murdered when they have tried to make peace. So Zelensky is going to need the fullest possible backing of the west when it comes to making a peace deal. And I don't see that at present.

Ray McGovern (01:07:16):

I agree with Anatol on that. I think that Biden has it within his power to tell the Pelosis and the Schumers and the high level military commentators on Fox and BSNB, and the rest of them to knock it off and to say, look, we're going to stop the carnage right now, and I'm going to tell Zelensky to be serious about the negotiations and give him his head in working out a deal. Now, that might not work, but that will be a different situation than it exists now. Right now, we're just happy to sell more arms. I mean, your arms that were destroyed, all those arms that's destroyed by Soviet missile attacks, they're making matters, clapping their hands because they will have to be replaced. In other words, the Pope was right. It's the bloodstained alternators that are behind us. And of course, they control the media. That's big. That's what Eisenhower warned us against.

Helena Cobban (01:08:27):

So I'm going to throw a curveball in, I know curveball is a bad term in the context of a build up to war, but here's one for you. Do you think maybe people in China in decision making areas are just happy to see Russia and NATO duking it out over there at the Western end of the Eurasian landmass?

Ray McGovern (01:08:55):

Yes, I think so.

Anatol Lieven (01:08:59):

I'm not sure. Actually. They don't seem to be terribly happy, partly because, of course, of the effects on the world economy and on energy prices, which have a direct effect on the Chinese economy. I mean, clearly, there is a certain satisfaction and obviously very deep feeling against NATO and the US, but also, it seems to me, I mean, the Chinese have been very cautious so far about actually helping Russia economically, and I mean, that will be the key issue. Are they prepared to prop up the Russian economy in order to keep Russia fighting in Ukraine? Well, propping up the Russian economy will be a pretty formidable task, even for China. So I wonder whether the Chinese have been built up into this great sort of huge reckless bogeyman. But actually, it seems to me that with the sole exception of the South China Sea, the Chinese have behaved with tremendous caution, actually in recent years in most parts of the world.

Ray McGovern (01:10:24):

But the Chinese have already lifted all restrictions on the import of wheats and soybeans from Ukraine, from Russia. In other words, they're defeating the sanctions that way. They've also done other things that suggest that the US dollar has seen its best days. And this may not be seen as explicit cooperation to save Russia, but it is the alternative, the alternative universe. Now we have a bipolar world once again, but this time it's NATO and the US against China and Russia. And, you know, that old triangular thing. Well, it's a nice oscillation triangle now with the US at the short end. And it's high time that Putin's advisors got onto that and told them that there are real limits as to how you can affect the world economically and other ways.

Helena Cobban (01:11:32):

Hang on. You mean Biden's advisors or Putin's advisors? You said Putin.

Ray McGovern (01:11:43):

I'm sorry, I meant Biden's. Yeah. Thanks very much. Again, I've said before that Biden's advisors do not inspire confidence not only in the foreign policy realm, in China especially– but who is advising him on economic affairs. What he has unleashed is a God-awful chaos in the whole world that's going to affect everybody. And did they realize that? Well, the Russians and China are in this together. And to the degree that the military stuff happens against NATO, I could see the Chinese saying, well, at least we don't have to worry about the South China Sea or Taiwan for the next couple of years, probably. And that's got to be a good thing for Xi Jinping.

Helena Cobban (01:12:29):

I'm afraid our time is kind of coming to a close, but I know Richard wants to speak, and then maybe we'll ask both the guests if they have a couple of final words. So Richard. Yes. Yeah.

Richard Falk (01:12:42):

Well, first, let me say there's been a very stimulating and thought provoking discussion that I think has illuminated several of the key facets of this very complicated situation in the Ukraine. I would just add to the discussion of the place of China that even before Ukraine, China's geopolitics was predominantly economistic outside its own region. And that would lead me to think that it isn't taking much comfort from the continuation of the Ukraine war or its broader ramifications. So I think China is the most responsible geopolitical actor we have in the world at this stage. And part of the regressive features of Biden's foreign policy was this geopolitically confrontational approach taken to China almost immediately when he arrived at the White House.

Helena Cobban (01:14:09):

That's a really important point. Richard, thank you so much. I just want to come back and give well, certainly thank both of our guests, really, for wonderful engagement, wonderful presentations, and so much more for us to all think about. Anatol Lieven, would you like to give us two sentences to take away?

Anatol Lieven (01:14:34):

Well, just that, as I say, I think that a reasonable peace settlement is becoming possible now and that I really hope it can be reached because I think the basic terms will be the same months or years down the line, and the only difference will be that tens or hundreds of thousands of people have died. And so I would urge everybody to do their utmost, whatever we can do to try to help bring about an early peace settlement and try to make sure that the United States and other democracies actually support a peace settlement instead of covertly undermining.

Helena Cobban (01:15:13):

One important point. Thank you so much. And Ray McGovern, two sentences, not more.

Ray McGovern (01:15:23):

The only thing that hasn't been mentioned is nuclear. We learned recently, I learned recently, that the Russian early warning system is deficient and that Putin would have only eight minutes to decide whether he's under nuclear attack. Those are the realities. That is a situation that has to be fixed. I think we can figure out ways to fix it. But I'm already over my two sentences. I would suggest that Richard and you, Helena, to be the intermediaries to be the moderators of the Ukraine, China, Russia. You should insert yourself now before it's late. Thank you for inviting me.

Helena Cobban (01:16:18):

No, it's been great to have both of you. And I would just note that Monday of next week we're going to have two experts on nuclear deterrence and the fragile psychology of nuclear deterrence, Cynthia Lazaroff and David Barash. We should probably have had people talk about the nuclear dimension of this at the beginning of the series because we've now had 30 years of Americans growing up without really having to understand nuclear deterrence and mutual deterrence, which is what we're now seeing nuclear has to be in the discussion. So thanks for that reminder, Ray. We have such a lot more to talk about. People attending this webinar can find details of the whole of the upcoming schedule while we have two more sessions, one on Wednesday and one next Monday. Go to our website, www.justworldeducational.org, and learn about the upcoming guests. When you go to the website, please don't forget the Donate button. This whole Just World Educational is run on grassroots support. Right now we're kind of going ahead on fumes. So as I said earlier, we need more fumes here. Please donate. As you exit the webinar, you'll find an exit poll. It would be great if you could fill it out because it really helps us plan our programming.

And the next webinar in this series on Monday, sorry. Wednesday, March 23 at 02:30 p.m. Eastern, will feature Phyllis Bennis of the Institute of Policy Studies. And with us from Sri Lanka, the writer and analyst Indi Samarajiva, who will give us once again a view from the global south on this conflict. So thank you very much, Ray McGovern, Anatol Lieven. And Richard, I'll see you on Wednesday!

Richard Falk (01:18:24):

Look forward to it.

Anatol Lieven (01:18:26):

Thank you so much. It was extremely interesting.

Ray McGovern (01:18:29):

Thanks very much. Bye.

Speakers for the Session

Helena Cobban

Prof. Richard Falk

Anatol Lieven

Ray McGovern

Support Just World Educational

JWE has a golden opportunity to make a difference in this country...

Stay in touch! Sign up for our newsletter: