Video and Text Transcript

Transcript of the video:

Helena Cobban (00:03):

Hi, everybody. I'm Helena Cobban, the President of Just World Educational. Welcome to the second session of the Webinar series “The Ukraine Crisis: Building a Just and Peaceful World” today. It's Monday, March 7th, and our two guests are Ambassador Chas W. Freeman, Jr. And Katrina vanden Heuvel. I'll give them more complete introductions very soon, but for now, let me hand over to my co-host, the distinguished international jurist Richard Falk.

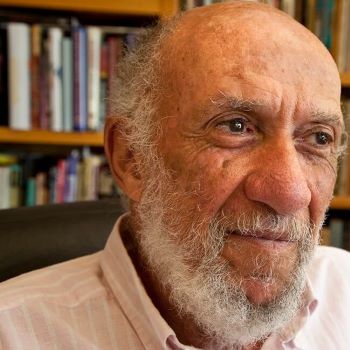

Richard Falk (01:01):

Thank you, Helena. It's a real pleasure and honor to welcome Chas and Katrina to our series. And they are superbly qualified to enlighten us about various dimensions of this complex, confusing, and very threatening turn of events, both geopolitically and from the point of view of international law and humanitarian considerations. I look forward very much to what these two distinguished commentators have to say.

Helena Cobban (01:51):

The video of the previous session that we had in this series with Vijay Prashad and Lyle Goldstein talking with Richard Falk and me, and information about the whole project has been posted on our website, www.justworldeducational.org. Today we're going to have a fairly free flowing conversation once again with our two guests, and it'll last roughly 45 minutes. After that, I think Ambassador Freeman is going to have to leave fairly early, and we'll hope to have a chance to say goodbye to him at that point. But there will also be a chance for questions from the attendees, which attendees should put into the Q&A box here. Also, I know that emotions and tempers are very high at the moment. There is a lot of suffering. There's a lot of anxiety. I just ask people to keep their interventions in this process, whether in the chat box or if you're invited to come with us on air to keep your interventions as civil as possible, because, of course, there are always disagreements.

So now, first of all, it's my big pleasure to introduce Ambassador Chas W. Freeman Jr. who is a veteran American diplomat whose career highlights included being the interpreter for President Nixon during his breakthrough visit to China almost exactly 50 years ago. Chas also negotiated in Spanish with President Fidel Castro over the parallel Cuban and South African withdrawals from Angola, and he served as US ambassador to Ryadh during Operation Desert Storm in 1991. His books include America's Continuing Misadventures in the Middle East and Interesting Times, China, America, and The Shifting Balance of Power.

So we'll have to come back to you in just a moment, Chas Freeman. Now I want to tell you a little bit more about Katrina vanden Heuvel. She is the publisher, part owner and former editor of The Nation, where she was editor from 1995 to 2019. Katrina contributes a regular column to The Washington Post. In 1919, she was the co author, with her spouse, Professor Stephen F. Cohen, of Voices of Glasnost: Interviews with Gorbachev’s Reformers, and in 2002, she edited the anthology A Just Response: The Nation on Terrorism, Democracy, and September 11, 2001. So a big welcome to both of our guests. And I'm going to come to you first, Katrina, to ask you to provide a quick version of your take on the current situation. I know it's changing all the time. And tell us a bit about what you think it means for Russia, NATO, the region. Also, if you have an assessment of the clarity of President Putin's decision making and the support he has for his policy among Russians, that would be great.

Katrina vanden Heuvel (05:21):

Thank you. I want to quote– and it's an honor to be on with Ambassador Freeman and Richard Falk. And you. Thank you– Anatol Lieven wrote a very important piece for The Nation a few months ago which laid out at that time the prospects for a settlement of the Ukraine crisis. At that point, there was diplomacy on Minsk accords, which I'm sure many know about, and the ability to build a free, sovereign, independent, non-aligned Ukraine. That was a few months ago.

He wrote the other day that historians of the future should condemn Russia for its Ukraine and will, but they will not forgive the west if we fail to promote a reasonable peace. And the voices of those in the west who favor sacrificing innumerable Ukrainian lives to advance other geopolitical ambitions against threats that resisted.

Let me speak briefly about Putin. I was on a radio show the other day and asked if Putin was crazy, was deranged. I think that avoids politics. It's simple. We did it with Trump that he was crazy.

Putin came to power in 2000. The first act in power was to give Yeltsin and his family immunity from prosecution for corruption.

I just want to select a few dates to understand Putin. In 2008, the Munich Security Conference at the height of the Iraq war, Putin explained to those in attendance that it was no longer a unipolar world and that Russia was back. And then you had the expansion of NATO to Russia's borders.

NATO today, I think, will be empowered by these last weeks. The armchair warriors in Washington are active and NATO is at the moment in the center of weapons shipping into Ukraine. We can talk more about the broken promise of NATO, but Putin is being viewed by reporters who I trust, veteran reporters, Fred Weir, very well connected Russian reporter. There's talk of his isolation inside the Kremlin. Some of you may have seen his dressing down of three top officials. And his isolation is best defined by those tables, those long tables he met with, 30ft. He's been affected by the COVID pandemic. It's reported he's been very paranoid about getting COVID. But how he's getting information, how he's processing it is a question because he's very isolated. And it is the case that the Siloviki, the intelligence, and military forces are really the ones he's in close proximity to.

And I think there was a terrible miscalculation and how much the west bears responsibility is going to be something to study, but the miscalculation of moving beyond the recognition of the two republics in Donbas. I don't speak out of school, but I work with Ambassador [Jack] Matlock. These are people who've spent their lives studying Russian who were deeply shocked. But the diplomacy broke off.

I think there's a fury and an anger on Putin's behalf that plays a role. But protests in Russia are not just those on the streets. The foreign policy elite issued a strong letter coming out of the school Lavrov graduated from. 20,000 cultural political figures, 150 governors, not governors, but regional elected figures have protested. And of course, the media blockdown is dangerous. But there is resistance, and I think that's important. It is the urban elite. But I think I'll stop here because Ambassador Freeman understands the Afghan, two things about Afghanistan, which we just exited. They're literally shipping weapons left in Afghanistan to Ukraine, and the body bags which came back to Russia after Russia, Soviet Union's involvement in Afghanistan were very pivotal in turning the country against the war.

There are mothers against the war in Far East regions, some around big cities. And I think the body bags coming back could play a role. But the weapons shipments-- my colleague Michael Klare is very concerned about nuclear escalation. And if there is an attempt on Russia's part to bomb lines coming from Poland with weapons, you could see a widening and a dangerous escalation. So I don't have any good news, but I’ll turn it over.

Helena Cobban (10:34):

Katrina, your depth of understanding, knowledge and contact with the people in the system in Russia is very much welcome here. I'm going to turn to you, Chas, and obviously note that the meeting that you interpreted for in 1972 between President Nixon and Mao Zedong signaled a big transformation of the global balance at the time. So do you see the current Ukraine crisis as signaling another equally big transformation?

Amb. Chas Freeman, Jr. (10:34):

I think it's actually much bigger. The Nixon visit to China was a bold move that changed the course of the Cold War and eventually helped bring the Soviet Union down. This is the end of the post-Cold War period. That's what we're seeing. But it's more than that. It's also, I fear, the end of the effort, which began with the European Enlightenment to regulate international behavior with something resembling the rule of law. And we are seeing, I think, a reversion to the unprincipled uses of force that characterized the Napoleonic Wars.

I don't know why Mr. Putin did what he did, but I think it is very likely that it is the worst strategic decision that any Russian government has made since Tsar Nicholas II decided to go to war with Japan in 1904. And that set in motion a bunch of trends inside Russia that ended with the fall of the Tsar and his replacement by something arguably worse.

To go to the Napoleonic war analogy, Ukraine has the potential to become for Putin what Spain became for Napoleon. British gold helped finance the Spanish people's war. American weapons transfers now seem to be aiming to do the same in Ukraine, and I share Katrina's concern about where this is likely to lead.

I'd add that if aircraft from the Ukrainian Air force, which have taken shelter in Poland and Romania, stage bombing raids or attacks from those countries, they're very likely to suffer from not only hot pursuit but perhaps an escalating counterblow from the Russians. Meanwhile, we're seeing urban warfare to go back to the idea of the rule of law having been superseded. We're seeing urban warfare that's following Israeli precedents in Beirut and Gaza. It's not yet at that level, but it's headed in that direction.

All this was probably totally unnecessary. Russian coercive diplomacy, the massing of troops on Ukraine's borders, the demand for the neutralization of Ukraine, or at least its denial to the US and NATO sphere of influence, the implementation of Minsk II within Ukraine, and some effort at threat reduction on Russia's Western borders were comprehensible. They were clear objectives. They were arguably achievable.

But things have moved on with the invasion and the military incompetence that it has demonstrated. Mr. Putin may well have moved the goal posts. I know that the talks on the Belarus border began with Russia arguing for recognition of its incorporation of the Crimea and Donetsk and Luhansk in the Ukrainian East, and the demilitarization of Ukraine. And Ukraine went there with proposals for a ceasefire, the total withdrawal of Russian troops, and later added a demand for accelerated entry into the European Union.

We're seeing an apparent effort by China to run into mediation. This would be a supreme irony, because 100 years ago, roughly during the Versailles Treaty, European powers were redefining the spheres of influence they had established in China. For China now to be asked to redivide the spheres of influence in Europe is a mark of its rise to global power. And a supreme irony.

There's no role for the US in this. The US is characteristically responding primarily with military and other coercive means rather than any sort of diplomacy, and it won't be at whatever mediation takes place. I think, however, there is the basis for a deal if everybody can overcome the emotional stress and hysteria that you referred to, Helena. And it's always been there, really: on the model of the Austrian State Treaty of 1955, Ukraine could declare neutrality. A treaty incorporating the provisions for minority rights, linguistic and otherwise, envisioned by Minsk II, could be endorsed by the relevant great powers. There could be referenda – OSCE supervised, perhaps – internationally supervised referenda in Crimea, Donetsk, and Luhansk, leaving the results of their choices whether to be part of Russia or be part of Ukraine or be independent, to be decided by voters, so no leader has to take responsibility.

And while there can't be demilitarization of Ukraine as Russia now demands, certainly Ukraine can abjure NATO membership as an aspiration. Finally, I think Ukraine's effort to join the European Union offers an opportunity. Why not couple that with simultaneous membership in the Eurasian Economic Union, something that Brussels, Moscow and Kiev could work out, which would enable Ukraine to take on the role that it should have taken on after the end of the Cold War and the breakup of the Soviet Union, namely, a bridge and a buffer between Russia and the rest of Europe.

So I think that is there. But we may not see that, and we face various scenarios which are really quite frightening.

Suppose Mr. Putin loses but remains in power, and Russia is aggrieved and belligerent. Suppose we fail to incorporate Russia into the councils of European governance as we failed to incorporate Germany into those councils after World War I? That catalyzed World War II and the Cold War. And suppose that Ukraine retains its independence and sovereignty, but now as part of a divided Europe. These are all possibilities. And we've thrown into the mix German rearmament and a much greater weight for Germany and European Affairs than had previously been the case.

And we don't know the course of Sino-Russian relations, Sino-US relations, and Sino-European relations. So, there are a huge number of imponderables out there, none of them very cheering. And I'll stop there.

Helena Cobban (19:21):

Wow. Thank you, Chas, for giving me an amazing global tour d’horizon there. To a degree, I guess quite depressing. So, Richard, as co-host here, I'd love to hear something of your views about, I think we all would, about the role of the United Nations in this crisis, where it seems to me to have been sidelined. But perhaps you could look at its role in equally serious crises earlier on. Or indeed, we could come back to the question of international law that Chas raised as being itself under threat right now.

Richard Falk (20:05):

All those issues you mention are part of this discussion that has been so usefully started by Katrina and Chas. Let me say that it's important to understand that the UN was designed to give political space to geopolitical actors. Otherwise, the right of veto in the Security Council makes no sense. In effect, the UN was structured in ways that acknowledged that it did not have the capabilities or authority to govern geopolitics. A Mexican delegate at the time of the establishment of the UN said, we've created an organization that holds the mice accountable while the tigers run free. That's an important reality. And I would differ slightly with Chas about this Ukrainian aggression doing decisive damage to the rule of law. I think the decisive damage was inflicted previously by the US in its Iraq regime changing intervention, and by the Nato interventions in Libya and Kosovo. And then going back further by the Afghanistan intervention and even the Vietnam war. Not only were these damaging to the global rule of law by the country that purports to be most committed to the promotion of a law oriented foreign policy, but these interventions exhibit the reality of this geopolitical exception to the prohibition on aggressive uses of force. International law governs the behavior of normal States. It does not govern the behavior of geopolitical actors dealing with war, peace issues or matters of grand strategy.

And in a way this feature of world order was also reinforced at the end of World War II by the framing of the Nuremberg and Tokyo war crimes trials, that is, holding accountable the political and military leaders of the defeated country, but giving impunity to the victors. In effect, the message is that if you win war, a geopolitical norm validates holding the leadership of the losing side accountable. If a geopolitical actor is successful in major warfare, it becomes permissible to hold the defeated actors accountable without sacrificing your own impunity. And that is inscribed in the operational code of geopolitics since 1945. I think we have to understand the depth of this geopolitical dimension of world order to grasp how it operates. And that leads me to think that what Chas emphasized in terms of spheres of influence is partly the broader context of what's at stake, because the geopolitical norm at issue was the acceptability of spheres of influence. It's not an international law norm, but it is a geopolitical norm. And when Putin said, and I think it was a very apt quote to call our attention to, this is the end of the unipolar world, in effect, what he was saying is that other countries beside the United States have an entitlement to protect their spheres of influence against the intrusion of geopolitical rivals. And that's what in some sense, Ukraine is all about, because in the unipolar world, the whole world became the US sphere of influence.

It seemed like a revival of the Monroe Doctrine, but extended to encompass the planet as a whole. And that seemed to me to be a kind of reasonable reaction on a geopolitical level of discourse, Putin contending that there now exists either a restored bipolarity or possibly a tripolar world which has never existed before, at least not on a global scale. And this calls for this search for what Katrina called a reasonable peace, which I think would be very helpful to get further elaboration, with some sensitivity to the relevance of the changed geopolitical context - I think both Katrina and Chas have already provided us with some indication of what a reasonable peace might constitute. The Pugwash group of scientists issued their own eight-point program that went pretty much along the same lines, advocating ceasefire, withdrawal, neutralization, and an attempt at diplomacy rather than at coercive measures. Let me stop there.

Katrina vanden Heuvel (26:28):

I wanted to pick up because this is not related so much to the international law, but it does speak to, I think, an extraordinary moment at the UN in December 1988, when Gorbachev gave a speech, really, it was a moment where you felt the Cold War was over, that Cold War, and it was part of his new thinking of that perestroika era, and it was ahead of its time. It was visionary, but it was realistic, and it spoke of common European homes stretching from Vladivostok to Lisbon, words that Macron of all people in this last period, used at moments in a quest for a new security architecture more independent of the United States and NATO, channeling his inner de Gaulle. But what is realism? Is it more militarism, is it more military weapons, or is it a redefinition of security, which at this moment seems so central to the new thinking of our times, climate crisis, pandemics, global instability, global inequality, displacement of people. So I think it's somewhere the ability to return to a sense of new security and rethinking what security means is critical.

And I do think there is the reasonable peace I mentioned, it's really something Ambassador Freeman spoke of, it is the case, and it's worth going back to see that for a brief moment. And again, it's really lost now, but Putin offered to Ukraine to join the EU and the Eurasia Association. It was a tripartite offer, very briefly extended and then pulled back. But to repeat what Ambassador Freeman said, yes, the neutrality, the buffer, the language rights in Eastern Ukraine, independence and sovereignty of Ukraine. But I think even the very serious advocates of Minsk understand there has to be a new way now because it's moved to a point. But there's a cynicism. I mean, no one wants US men and women, no one wants any men and women going to fight in Ukraine, but the United States will arm Ukraine to fight to the last Ukrainian. And it's terrible. The ability to find a ceasefire and peace, a reasonable peace seems to me the priority at this moment. And then we turn to thinking about what I was saying.

Helena Cobban (29:20):

I do think that's really important that you put in the need for the overarching planetary needs right now. Just last week we had the issuing of a new report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. And this crisis is not only obviously, as all military crises do, exacerbating global warming in a terrible way, but it's also holding up wheat shipments that are desperately needed throughout Africa and much of the global south. So is there a way to get thinking back to the global good of humanity? I'm not sure there is in the midst of a crisis such as the present, where we are also looking at possible nuclear triggers. What do you think chairs about the risks of nuclear engagement?

Amb. Chas Freeman, Jr. (30:17):

I don't think tactical nuclear weapons are relevant to the military situation in Ukraine. The Ukrainian forces are dispersed, not concentrated. Tactical nuclear weapons would be useful against heavy armor in one location. That's not the issue.

The danger is that Russia's basic claim to be a global power rests on its nuclear arsenal. And there might be a temptation to use a tactical nuclear weapon in Ukraine just to demonstrate the willingness to cross the nuclear threshold. And I think that is a frightening prospect. If I may, I'd like to comment a bit on Richard Falk statements, which I find myself completely agreeing with.

First, I think the invasion of Ukraine and Mr. Putin's constant escalation of his aims there is the culmination of a long process of deterioration, much of it caused by US unilateralism. And I won't rehearse all of the developments there, but there are ironic situations, like the vivisection of Serbia to produce an independent Kosovo, which was, I think, the precedent for Crimea going back to Russia. And, of course, the wars in the Middle East.

I think this is entirely about spheres of influence. The UN, as Richard said, enshrined the concept of spheres of influence in Franklin Roosevelt's four policemen concept, which became the basis of the Security Council at the last minute. The fifth Horseman, France, was added by Churchill out of deference to de Gaulle, but also because France has its own sphere of influence, primarily in Africa. So you had that principle in the Security Council, and then you had the Westphalian principle of sovereign equality in the General Assembly, which unfortunately, no one pays attention to.

So as Richard said, after the end of the Cold War, the United States basically extended the Monroe Doctrine to the entire world wherever we could, except for China, Russia, North Korea and Iran. Everywhere else, we demanded a say in the policies and alignments of countries everywhere. So the Russians began with an effort to deny us the incorporation of Ukraine into our sphere of influence. That has now apparently escalated to an effort on their part to rebate a sphere of influence of their own, which would include Belarus and Ukraine and operate very much like the Monroe Doctrine has in the Caribbean Basin.

Final observation, the US in the period of unilateralism basically paid no attention to the UN Charter, the Geneva Conventions, or various other pillars of international law. And then more recently, it has been expanding something called the ‘rules-bound order,’ which is not the same thing as the UN Charter and international law, because it envisages the United States and a handful of former imperialist countries in the G-7, making the rules and enforcing them while determining which rules they should comply with or not. And this is understandably not acceptable to other major powers.

Back to spheres of influence, just for last thought, I think spheres of influence work when power balances are stable, not when power is in the process of rearranging itself, as it is now with the rise of great powers, the return of great powers or civilizational powers like China, India and Russia. And I don't think in circumstances where balances of power are dynamic, spheres of influence are anything other than a provocation. Basically the effort to incorporate Ukraine into the US sphere of influence at the very moment when Russia felt it was returning to a level of power it had not had precipitated this crisis. This is not to excuse Mr. Putin, whose reasoning I find quite incomprehensible in terms of what he did as opposed to what he started trying to do. But I think Richard is right. This is a combination of a long process. It has to do with fears of influence, and I fear, the birth of a new lawless world order.

Helena Cobban (36:03):

Richard, any comment on that, or should we–

Richard Falk (36:06):

No, I think that was an extremely useful sequel to what I tried to introduce by at least addressing this frequently unrecognized characteristic of the UN. And I think it was useful to recall that it was Roosevelt's idea that you would correct a defect in the design of the League of Nations by giving political space to maneuver within the UN to these geopolitical actors. And as he suggested, Westphalian statism for normal states, geopolitics for the great powers. Before the UN, geopolitical actors were called great powers. There is a dual normative structure composing world order. One interesting feature of this dual structure is that international law, by and large, emerges out of agreements, and the norms are established through the agreement of sovereign States. Geopolitical political norms emerge from precedents. And unfortunately, the United States set very bad precedents by its embrace of unilateralism in the form of regime changing interventions carried on over quite a long period of time. It's very important to keep that in mind, that when NATO acted as it did in Kosovo, a precedent was set that others can use. When the US engaged in atmospheric testing of nuclear weapons, it didn't want anyone else to do that kind of testing, including France, an ally, but it was helpless to object because we had done it previously ourselves under a claim of right. In other words, the geopolitical actor can establish a precedent, but it must live by the precedent establishes other geopolitical actors can take advantage of.

Katrina vanden Heuvel (38:39):

In terms of your terribly depressing thought about lawless world order. Is it possible, Ambassador Freeman, it might be rules of the road made by what we see, you know, the call for Liberal international order is not a universal rule of law. It's what we have decided. It's the rules of the road. I'm just wondering if that is something we may look out at. It's a brief point, but the Munich Security conference this year was something that people pointed to in the last days, towards Putin's terrible, grave criminal miscalculation, that Zelensky in Munich spoke of something we haven't spoken of, which is the violation of the Budapest memo, the Budapest memorandum, that, in fact, no one had come to their aid and there would be an attempt to reconstitute their nuclear weaponry. Now, this was said in an audacious moment, but inside Russia, inside Moscow, there was a kind of alarm of that. The ending of the Soviet Union has played a role in this, too, because what Putin seeks is not a reconstitution of the Empire. He's constantly misquoted. He didn't say it was the greatest disaster, the collapse of the Empire.

He said it was one of the greatest disasters of the 20th century. But the effort to reconstitute a Slavic Union is real. There were efforts years ago to start a Belarus Russian Union. Those collapsed but it is part of this mythology. Ukraine, Belarus, Russia. Two last points. I'm interested in your view, all of you, about sanctions. I think sanctions have been overused in ways that have harmed ordinary people. And there is harming of ordinary people in Russia right now. And the oligarchs, they've made their pact, so they're not being harmed. And the Russophobia is very dangerous in my mind, because there are Russians protesting the war, but their representatives. I don't know if you know David Cicilline, good Democrat, he sponsored a piece of legislation to oust Russia from the UN. There's a piece of legislation by a good Democrat in California to oust Russian students who are studying here. The boycott in the cultural world is as severe as anything I've ever seen, and that's, of course, within a certain sphere. But culture has been used over the years to re-engage. And then finally on nukes. I do think it's a moment of grave danger, but I think it's a moment where people, unlike the end of the Soviet Union when people decided there was no nuclear danger anymore, the nuclear danger is very much on people's minds, and I think just this is very different than the intellectual talk.

But June 12, 1982, a million people were in Central Park, and their protest on the eve of the Disarmament Conference at the UN played a role in moving the INF forward and abolition of a class of weapons. This is out there. But I'm just saying one thing we haven't fixed on is the unraveling of the arms control infrastructure. 2002, the ABM was foundational, and we've seen them all unravel. And even at the height of other cold wars, there was a compartmentalization of security discussions, arms control. This may not be possible anymore, but there was that happening even in bad times. But I'd be very interested in sanctions from the perspective of international law.

Helena Cobban (42:49):

Thank you, Katrina. You raised so many important points there, including this kind of just eruption of anti-Russian jingoism in this country, and I think in most of Western Europe as well, or maybe Eastern Europe as well as Western Europe. And I mean, to me, it's so noticeable that it just suddenly came up. And maybe it's a way for the wounded egos of people who withdrew from Afghanistan in virtually complete humiliation, that at last here's a cause that we can all jump on and be the west again. So it seems to me to feed some kind of psychological need as well. Of course, you know, one has human empathy for the people suffering under bombs and whatever, but noticeably less than one had for people suffering under bombs in Gaza. You know, there is something about the double standard here. The question of sanctions, I think, was your central question: Chas or Richard?

Amb. Chas Freeman, Jr. (44:02):

Maybe I can start on that if I might, huh? I just want to make one comment on Russophobia. There are few sights uglier than the American people in one of our bouts of moral indignation. This is what we do. It's morally reprehensible, but equally important, it's very dysfunctional in terms of statecraft because it substitutes rage for a reason. And we're not seeing diplomacy addressing the question of how to preserve an independent Ukraine in circumstances of peace in Europe. What we're seeing is a set of punitive actions against Russia, which are enormously gratifying to the people who are experiencing Russophobia.

This brings me to sanctions. Sanctions have a long history. Basically, they have been in the American toolkit since Jefferson tried to impose them and caused the War of 1812. Woodrow Wilson was a great apostle of them and imagined that economic warfare through sanctions could obviate the need for military action.

They have an almost unblemished record of failure, in fact, when they have been imposed at their most extreme, as they were in 1941 on Japan, what they do is provoke a reaction – in that case at Pearl Harbor. So if you put sanctions of a sufficient level of ferocity, maximum pressure, as it has been called in the case of Iran or North Korea, you are gambling with an unpredictable response.

Sanctions are useful as a threat, as part of a negotiation. That is, if they are accompanied by a yesable proposition, they can help persuade the other side to change course. But that's not what we're doing. What we're doing is finding pleasure in torturing the Russian people in the hope that they will then overthrow Mr. Putin, which hasn’t seemed to work usually elsewhere, I wonder why it should work in Russia.

Final observation. I think it's very strange that we have statecraft and diplomacy that appears to reject any idea of addressing the religious components of conflicts. Everywhere around the world we see a resurgence of nationalism combined with religion. That's the case in India. It's the case in Russia. My own visits to Russia have not been recent, but I recall being stunned by the degree of alliance between Mr. Putin's establishment in the Russian Orthodox Church and the rivalry between that Church and the one in Kiev as well as the one in Istanbul. This a very important underground factor in this whole thing that Mr. Putin, rather indelicately has given voice to. In fact, as he's gone along, he has begun to do something terribly foolish, which is to make this whole fight an existential one for the Ukrainians by saying ‘you’re not going to have a state.’ This is over unless you throw up your hands and surrender. And there are overtones to this in this of remembering Kievan Rus and the past connection of Kyiv to the foundation of Moscov in the center of the Russian nation.

So religion needs to be taken seriously, whether it's in the Holy Land or elsewhere. I fear too many of us overlook that.

Helena Cobban (48:33):

Richard, do you have something on sanctions that you'd like to say?

Richard Falk (48:38):

Just a word or two, I think that sanctions are, in recent US foreign policy, a continuation of its consciousness of having a unipolar control over the global system following the end of the Cold War. That's separate from their usefulness in the context of Ukraine. My sense is that they should have been kept as a sequel to failed diplomacy, that peace diplomacy should have been the priority, with sanctions, as Chas mentioned, as a residual element of incentive to reach a reasonable peace. I think if good will had prevailed, which is quite a leap of faith at this point, this diplomacy could have worked and still should be the primary diplomatic effort. And sanctions do have a terrible record of aggravating conflict, not achieving their stated goals, yet aggravating the suffering of civil society. Sanctions have been shown to be mostly dysfunctional, dubiously legal and questionably moral because of their effect on civilian society, rather than the alleged perpetrators of the wrong.

Katrina vanden Heuvel (50:49):

I'm sorry, Ambassador Freeman, what he said about religion. I said, and I say this with humility a few years ago, that you could not write about Russia without writing about the role of the Russian Orthodox Church, and it's ascendance and its fusion with the powerful. I mean, the church that Pussy Riot protested in is called the Oligarchs Church. It's called Putin's Church. The one who brought religion to the fore was Medvedev. He and his wife were extraordinarily religious, and she formed an anti abortion group. But just part of that problem is that we haven't really learned much about Russia except for Putin in the last years. I mean, it's really been Russia is Putin, and Putin is Russia. I think that allows one, and the horrors of the last days certainly allow the demonization. And someone I don't usually quote once wrote that the demonization of Putin is not a policy. It's an alibi for not having a policy. I think for many Americans, if there's any glimmer of anything, it's the sort of shock that they're Russians protesting. I wanted to say, forgive me, Chechnya. We haven't talked about Chechnya. On a much, much smaller scale. It was raised and bombed in the ways we're seeing. Horrific. It was really Yeltsin's war, and then it became Putin's war. But he came to power in that hyper militaristic way, and it's going to be 24 years in two years, weirdly, the same year as our presidential election.

This is a different Putin. This is a Putin who has gravely miscalculated and has shot his own country. I think Ukraine could soon look like [?] which is going to be how one gets to diplomacy. Last thing I'll say is diplomacy is not that respected in our country. I mean, I'm in the media and media covering diplomacy often takes a second. What's the word? It's not up there covering war, the drama. So we need to think hard about the importance of reviving diplomacy, even in this grave, horrible moment.

Helena Cobban (53:18):

Yeah. Thank you for that commentary about the media, Katrina, when I was a working journalist. It was always “If it bleeds, it leads.” And there's certainly been plenty of blood in Ukraine and all this very touching, emotional coverage of the suffering, the undoubted suffering of the people. But let's get back to diplomacy. So I'm actually going to come straight to you, Chas, because you'll be having to leave fairly soon. Tell us whether you think China can play a role in mediating the end of this.

Amb. Chas Freeman, Jr. (53:53):

I was going to lead off by saying that I don't think Americans understand diplomacy because we burst into the world as a hegemonic power. And in many respects, our diplomacy in the Cold War resembled Imperial administration more than it did efforts to persuade recalcitrants to do things our way. However, this war in Ukraine is probably not going to end happily or at all, on the battlefield. It must be ended in talks, and those talks are potentially there.

We now have the suggestion of Chinese media. I think the Chinese would be well advised to turn to the UN for support in mediation. What's wrong with them asking the Security Council, which Russia is a member of, to agree to assist them and work with them in mediation or to mediate with their support? An alternative would be for them to go to the EU and say, we would like to jointly offer our services as mediators.

There's not much experience that the Chinese have had in this, but then nobody has really I think the mediation of the Angola Namibia settlement that you referred to was one of the few instances where, despite the extraordinary unpopularity of the mediation effort, it actually in achieving its objectives.

So I would favor a combined effort. And I'm sorry to say the United States is not qualified to participate in that because it has to be led by a country or a group which is acceptable to both sides.

China is engaged in a straddle that is very uncomfortable for it. It supported the Russian effort to end NATO enlargement. It does not like spheres of influence. It favors the renegotiation of European security architecture. But on the other hand, it is the 21st century Citadel of Westphalianism. It strongly supports sovereignty, territorial integrity, and independence. And it has retained a relationship with Kiev throughout all of this, even as it has refrained from criticizing Russia for sound geopolitical reasons. So it has set itself up inadvertently, I think, as a potential mediator. But perhaps it needs the assistance of others like the UN or the EU. So I would favor exploration of that by Guterres and by von der Leyen and others.

Katrina vanden Heuvel (57:14):

Very interesting.

Helena Cobban (57:16):

So actually, what you'll be talking about would be something analogous to the role that the US played after the 1973 war, where with the agreement of essentially the Soviet Union at the time and the Security Council, it took the lead in mediating various strands of Arab-Israeli peace. I think that's a great precedent to be looking at, and I hope we can get to diplomacy as soon as possible. I mean, you say that Americans don't seem to really have much time or respect for diplomacy right now. Somebody made the observation that most of the people at the upper echelons of the political elite in this country came of age during the Unipolar moment. So they didn't really need to get down in the weeds of how you negotiate an arms control agreement or the cessation of the conflict in Namibia and Angola and so on. And that's a really sad state of affairs.

Amb. Chas Freeman, Jr. (58:26):

There is no relevant experience at the top of our government at the moment. I don't want to get into personalities, but the focus has been entirely domestic, not international. Even the President, who has been a figure in international affairs, has dealt with them primarily from a domestic political perspective. And that won't do.

We have two very aggrieved parties with a great deal of anger at each other who are engaged in killing each other and helping them to find a way out of that dilemma is not going to be achieved through expertise in American political campaigning or staff experience on the Hill. And I do have to leave. I apologize. I hope you carry on. And of course, now that I'm no longer at the table, you will put me on the menu, and that is fine.

Katrina vanden Heuvel (59:33):

Thank you for your tour de force.

Helena Cobban (59:36):

Thank you so much, Chas. Really appreciate you being with us and giving us so much wisdom. That was great. See you again soon, I hope. We will move on a little bit. We have a couple of questions in the Q and A section. One actually was who do you see as potential mediators for Ukraine? I think Chas gave a great answer there. Are there other answers that we could add to that?

Katrina vanden Heuvel (1:00:02):

I'd be interested in thinking about Israel. The Prime Minister arrived in Moscow the other day with one of his deputies, who is Russian, obviously Russian. Lieberman, I don't know if he's still defense Minister, but anyway, I'd be interested in your sense of that, because Zelensky I believe he's the second. There are two Jewish leaders in the world, Naftali Bennett and Zelensky.

Richard Falk (01:00:33):

Well, I don't want to depart from the Ukrainian focus, but there's a lot to be said about Israel and looking at this conflict from the Palestinian perspective, how it's being addressed by the world and even by the UN. And I think that Israel, somewhat like China, is trying to straddle the geopolitical fence because it doesn't want to alienate Russia and it doesn't want to abandon the only other Jewish leader in the world or the Ukrainian people. I think Israel would be well advised not to try to be a peacemaker in this context. As far as the more general comments that Chas made very coherently, I think the downside of what he was proposing is that the more complex you make a negotiating or mediating framework, the more cumbersome it becomes, the longer it takes to achieve agreement. And I really think the urgency of stopping the humanitarian tragedy should be more important than adjusting the great power dynamic. And that calls for an efficient mediation process that, as Chas suggested, is minimally acceptable to both sides, and thus perceived as legitimate.

Katrina vanden Heuvel (01:02:44)

So the Security Council, the UN, could be that?

Richard Falk (01:02:45)

The UN is not a suitable venue for this type of conflict resolution. I think its bureaucratic structures are too cumbersome. And I think that having two of the countries with veto power now contention, the UN could, if it was so entrusted, establish a mediation process either by appointing either a person or a government to undertake this. But I'm not sure that's an efficient way to go. There's no obvious candidates that seem likely to be acceptable to both Russia and the U.S.

Katrina vanden Heuvel (01:03:37)

Forgive me, we haven't talked about the OSCE. They have played a role. They did play a role in monitoring the end of the Georgian conflict. I don't have a sense of how efficient, but they have been mentioned as alternatives.

Richard Falk (01:03:52):

Yes.

Helena Cobban (01:03:54):

I think the OSCE, which is the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe, which grew out of the Helsinki Accords back in the 1970s. (It’s just that a lot of people these days don't even know this stuff. My daughter, who is very well educated, said, well, what does NATO stand for? Which is a good question, actually. What does NATO stand for?)

Katrina vanden Heuvel (01:04:17):

The interns at The Nation, I love them, but it's feudal history, which is now coming back anyway. But there's been more understanding in the last few weeks.

Richard Falk (01:04:32):

I think that suggestion is very good because it acknowledges the primacy of Europe in relation to the conflict. I think it doesn't pose the problems to the US that's choosing China as the mediator would pose. I'm sure that China wouldn't be acceptable in Washington. I think that is a fruitful and maybe further thought should be given. Katrina, maybe you should write something along.

Katrina vanden Heuvel (01:05:10):

Yeah, because there is a terrible urgency, as you said, Richard, this is not a time, though. One wants to think about what alternatives exist and what could be, but one has to stop the bloodshed.

Richard Falk (01:05:24):

Yes.

Helena Cobban (01:05:29)

So we do have one other question here in the Q and A, which is how can one balance the need to both denounce Putin's invasion and draw attention to US provocations that contributed to the crisis? I think that is something that a lot of us are dealing with. Katrina, Richard, do you have anything to–

Katrina vanden Heuvel (01:05:54):

I would ask your listener your question, and I say this with humility. The lead editorial in The Nation both condemned the illegal indefensible invasion, but also noted the US role over time with not just NATO, but other issues. And I think it's important in terms of history, but also, not morality, but international law and humanity to be able to hold two things in your mind at one time. I don't think the United States can be exempted from this history. Again, it's NATO, I think primarily, and its many manifestations. But the Unipolar issue, in any case, I think there is an ability to do it. I do think the climate in our country, I can't speak for Europe, is such that if you raise questions about NATO's role, there's a quickness not just on Twitter, but to be called a Putin puppet. And not just on Twitter, but if you recall, before the war, there was a very good journalist from the AP who asked the Defense Secretary spokesman, “I'm skeptical about the intelligence you're producing.” And the press person said you're parroting Russian talking points. And that's why you need skeptical journalism. You need to ask questions. And it shouldn't be defamed by smears.

Helena Cobban (01:07:37):

That's a great point. I think that was probably Matt Lee of the AP, who was asking for the evidence for all these assertions that were being made and nobody else was doing it in The New York Times or the corporate media. And that was exactly what got us into the 2003 invasion of Iraq, that Colin Powell went to the UN with all these assertions that had already been refuted in many places. But the mainstream media, and particularly The New York Times were just cheerleaders for the war effort and never asked for his evidence to be tested. And we know the disasters that the invasion of Iraq visited on that country, on our country, on so many other places in the world. So that was a great point. I think we're probably going to have to wrap up now. This has been a truly amazing discussion. Would either of you like to just say a couple of last words.

Katrina vanden Heuvel (01:08:45):

Have a secular prayer for a ceasefire and an end to the blood, and if there's a way to find a reasonable peace, Richard Falk many years ago came up with the cover for our issue after 9/11. It was a just response and I think a reasonable peace because we can't hope for too much. But ceasefire and end to the bloodshed. And I will say let's not forget the humanitarian conditions after we hope this crisis and war ends. We've seen that in too many places. Afghanistan, we've left humanitarian needs or such in other countries. So just a plea for humanity in a time of barbarism.

Helena Cobban (01:09:31):

Thank you very much, Richard.

Richard Falk (01:09:34):

Just to echo Katrina's very important points about ending the bloodshed and not forgetting the people of Ukraine. I mean, those two things seem to me to be appropriate priorities that have an urgency behind them. And the conceptual point I would make at the end is that it is important and appropriate to both condemn the aggression and to condemn the provocative geopolitics that created a context where conflict would cross violent thresholds, that there is a geopolitical dimension that cannot be excluded. And that the idea that these few States have the discretion to use international force when their strategic interests are served by is something that the rest of the world should not be willing to live with much longer. Here China is positioned to play a useful pedagogical role with respect to the geopolitics of force, favoring a geopolitical norm that incorporates Westphalian standards of respect for territorial sovereignty.

Helena Cobban (01:11:02):

Well, this is sadly going to have to come to an end. But I want to thank you, Katrina, very much for being with us.

Katrina vanden Heuvel (01:11:13):

An honor.

Helena Cobban (01:11:15):

We have a lot more to talk about. This crisis is going to continue. It's going to unfold in different ways. Katrina, you held us completely onto this straight line of let's get a ceasefire. Let's think of alleviating the humanitarian distress and let's figure out how to build peace for Ukraine and for the badly damaged world system. We're going to be having two sessions of this webinar every week through March 28th on Mondays and Wednesdays. So we hope that our present guests will come back and join us as they are able. And people who are attendees here can find details of the whole upcoming schedule at our website. justworldeducational.org at the website you will also find a donate button. We really are running this whole project on fumes and the more you can help us send us a few more fumes or large buckets of fumes. Massive great checks. Please do that at the donate button at our website. Also when we close down and when you exit the webinar there will be a little exit poll. You can really help us if you fill that out because it helps us plan our programming better.

Helena Cobban (01:12:43):

So Katrina vanden Heuvel. Thank you and Richard, see you again on Wednesday.

Richard Falk (01:12:50):

Looking forward. Very good to see you come back to watch for adding so much to this. Hopefully, you will return to add even more to our discussion as this Ukraine Crisis continues to unfold.

Katrina vanden Heuvel (01:12:57):

Thank you. It was really interesting to hear you, Helena and Ambassador Freeman, it was extraordinary and very helpful in this moment. Thank you.

Helena Cobban (01:13:09):

I'll just tell you all that when we will post the video of this onto our YouTube account we'll post the audio onto our podcast account and the transcript will also be on our website. So do just go to actually it's this link where you'll find all those resources. Just go to the front page of our website, www.justworldeducational.org and thank you all very much. See you again soon.

Richard Falk (01:13:38):

Thank you.

Speakers for the Session

Helena Cobban

Prof. Richard Falk

Amb. Chas Freeman, Jr.

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Support Just World Educational

JWE has a golden opportunity to make a difference in this country...

Stay in touch! Sign up for our newsletter: