Transcript: The U.S.-China Relationship with

Dr. Lyle Goldstein and Helena Cobban

Released on October 10, 2020

Video, Audio and Text Transcript

Download and listen to the audio file of this conversation: Dr. Lyle Goldstein and Helena Cobban, October 10, 2020

Transcript of the video:

Helena Cobban (00:10):

Hello, everybody. I'm Helena Cobban. I'm the president of Just World Educational. I'd like to welcome you to Phase II of our World after COVID project, in which we'll be focusing on the U.S.-China relationship and ways to de-escalate what sometimes seems to be an endlessly escalating balance between the two powers. Later in this phase of the project, we'll be presenting some sessions that are an exciting new collaboration we have with the Chongyang Institute for Financial Studies at Renmin University in Beijing, China. I'll tell you more about those U.S.-China dialogue sessions later on, but for now it's my pleasure to welcome Dr. Lyle Goldstein, who is a professor of strategic studies at the U.S. Naval War College in Newport, Rhode Island, and the founding director of the Naval War College’s China Maritime Studies Institute. Lyle, it's good to have you with us.

Lyle Goldstein (01:16):

I'm so glad to be here, Helena. Thanks for the invite.

Helena Cobban (01:20):

So now, just before we get into our discussion with Lyle, I want to remind you that, as with the first phase of this World After COVID project, all the materials in this phase will be archived and made available on a dedicated resource page on our website, at www.justworldeducational.org. And if you go there, you can also find a donate button and donate to support our programs. So now, I want to tell you more about Lyle Goldstein's amazing book that he published in 2015, it's called “Meeting China Halfway: How to Defuse the Emerging U.S.-China Rivalry.”

Now I was stunned, when I read the book, to see how many amazing Chinese-language sources he was integrating and using. And I think, you know, this book definitely deserves a very wide readership and thank you, Lyle, for writing it. I'm going to jump right in and ask you to explain one of the key concepts in the book, which is your concept of cooperation spirals.

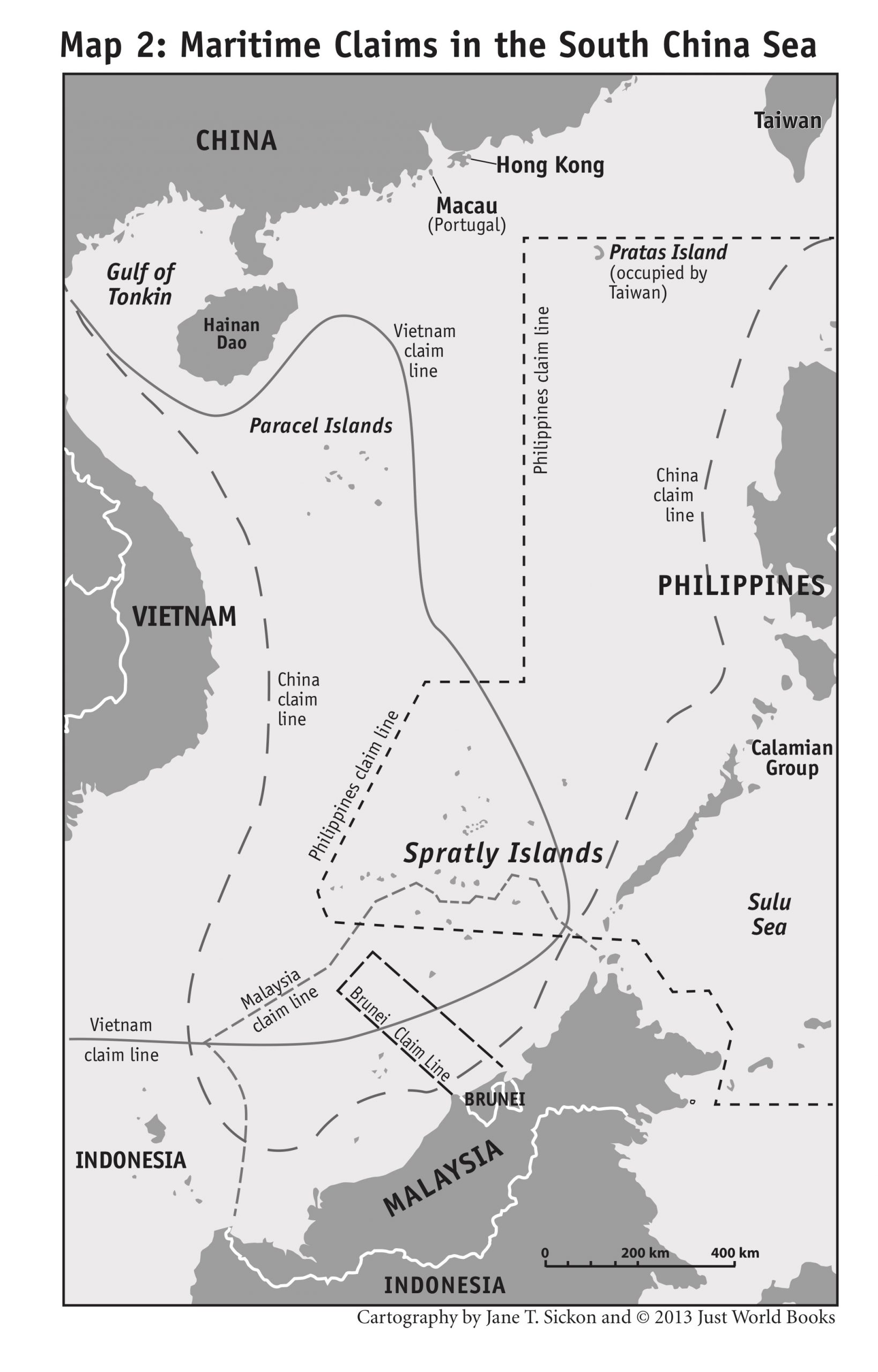

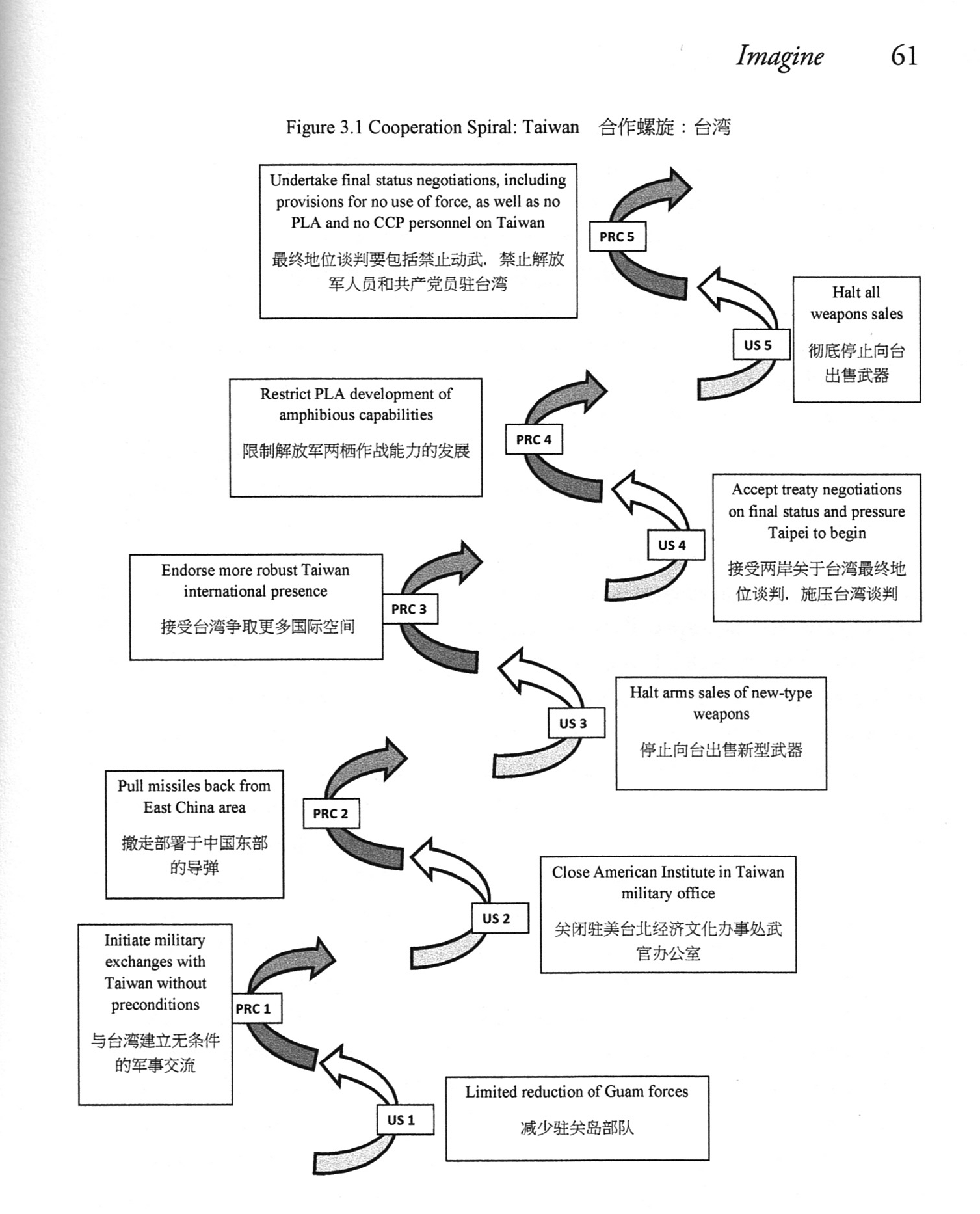

And we're going to share all this stuff on the website, but here's a picture of one of Lyle's cooperation spirals; basically, if you can't see what it is, it's a kind of a spiral of actions that one side takes and then the other side takes and so, U.S. one, PRC one; U.S. two, PRC two; and each is a series of graded steps, which he just describes in here, which he labels in both English and Mandarin. So Lyle, could you explain how you came up with this concept and then we'll talk a bit more about it.

Lyle Goldstein (03:23):

Well, sure. Maybe I'll just show you a kind of graphic there. Right, this is the concept of the cooperation spiral I developed. And it's, I don't want to pretend that it's something so novel. I mean, I think, at some level, you know, one learns to, you know, in your own family relations and at school and so forth, you know, one learns to de-escalate conflict on a daily basis where this kind of, well, you know, let's take some graduated steps toward compromise and that might lead to kind of greater forms of compromise.

So really this is very intuitive, I think for most people but it does have, I think, a strong social science basis. You have people who have studied cooperation using mostly social psychology, like Axelrod and Keohane, for example. They did some famous studies and they, they asked the question, they said, well, cooperation doesn't happen that much in the world, but, when it does happen, how does it happen? And what they came to the conclusion quickly that the best way to develop cooperation, the most successful forms of cooperation are really in a kind of tit-for-tat. That is, you don't jump into a kind of grand bargain. Rather, you, you make little steps building trust on the way, and those allow for the bigger compromises down the road. So indeed that's really what I try to build.

Lyle Goldstein (04:57):

And really what I wanted to do in this book is kind of fill out these these steps: you know, what might they look like? And I surely did not think that I was the person who had all the answers to this. There are a lot of brilliant Chinese thinkers and American as well, who have a lot to contribute to this and, and students as well. And, you know, whenever I give a talk about this, I always ask the students to come up with their own spirals and ask them how they would look. So here you see these four kind of principles though, that I think are essential gradualism, of reciprocity, of course, and fairness and some kind of enforceability. And I always understood that within these processes, one could go backward down the spiral. That is, I mean, in other words, you could fall backward.

Lyle Goldstein (05:52):

There might be setbacks, you know but, but still we could continue to move upward and onward. So, that's the general idea. It's a lot harder in reality. I can't say that I've seen too many examples of that. I mean, they're there, they're out there but it's, I would like to see much more of this. Unfortunately we seem, as you can imagine, you know, the reverse of a cooperation spiral forces an escalation spiral, and unfortunately that has been the dominant trend. So I am, you know, you may be wondering, I am asked occasionally, and I'll just stop sharing the screen here, although I might share a few more details later, but I am frequently asked, you know, “Oh, Professor Goldstein, do you regret proposing that we should meet China halfway? You know, have you rethought all this and come to the realization that we have to confront China across, you know, all dimensions of Chinese power and so forth?” which is the kind of discussion one hears more and more in the U S government and around.

Lyle Goldstein (06:57):

And, you know, I have not. I don't think that's right. I, you know, I frankly reject that premise. And in my view, we failed in many respects to meet China halfway. That is, you know, had we undertaken more, bolder steps earlier, we'd be much, you know, I think we'd be in a much better place. Now, one could argue it's too late now. One could argue there's so much bitterness in the relationship that that these proposals are not practical now, but I really don't think that's true.

I think we can, there are a lot of reasonable people on both sides, you know, the harder people think about it, they come to conclusion that conflict is just out of the question, especially in the nuclear era. So how do we come together? And, and I think you know, I don't think all is lost there. I think we can get back to a positive relationship. It is going to take a lot of work, though, and a lot of compromise, and compromise is hard. Yes, absolutely.

Helena Cobban (07:54):

That's a great introduction to the concept. Thank you. I have a little follow-up question actually, which is: You alluded at the end to the fact that the prospects of outright escalation are so terrible. You know, which is, if you don't go up to the cooperation spiral, but you cascade down it into greater and greater escalation, you may end up with truly horrendous outcomes.

And I know you've written about this a couple of times recently in “The National Interest.” Or maybe these were articles that you had written earlier, but they re-upped on “The National Interest” magazine, which I was really pleased to see. One was about Taiwan. And another, I think was about China, the Chinese Navy’s, or the Chinese military’s memories of of the China-Japan war. And actually now that you have this what they call the “quad,” the U.S.,Japan, Australia and India meeting just right now at a ministerial level in Japan, maybe these memories - the Chinese military has memories of what happened in the 1930s and 1940s - and maybe even before that, must be really on their mind a lot.

Sorry, that's a little bit of a digression from what we'd agreed to talk about, but I think that, you know, before we dive into one or two of the spirals that you laid out, it would be useful to have a sort of an update as of today for some of these things that you were writing about in the “National Interest” articles.

Lyle Goldstein (9:52):

For sure. And I have written a lot for “National Interest.” For about five years. I wrote a kind of weekly column and I'm, I'm a little sad to - I stopped writing it for a variety of reasons, but I'm a little disappointed that frankly, the editor seemed to, how to put it, they pick out actually the most, kind of, the darkest ones and tend to republish those for whatever reason. So I would encourage, if people are curious about my writings, they might just go down the list. Because the ones that are republished tend to have these very splashy headlines, I guess that's life in the internet age where these publishing outlets are paid by the click. So anyway, please take a look. You're right though, and I, you know, Helena I'm by training a China specialist, and I also work on Russia and speak Russian, but my you know, my training is mostly as a defense analyst and, you know, part of my motivation here is that these scenarios are very, very dark.

Lyle Goldstein (11:02):

You know, even in the best case, a U.S.-China clash would involve massive fleets of ships and aircraft, missile engagements of a kind that we've, the world has never seen. And of course you know, lethality and losses that would be massive. By my calculations, you know, a Taiwan conflict, for example, would probably mean certainly tens of thousands of Americans, probably dead, but probably in some total, maybe hundreds of thousands killed but it could go up from there. As you pointed out, escalation is something very hard to predict and I don't know any nuclear strategists who can say with a straight face, and I did my Ph.D. on nuclear strategy, so I know a few things about this, and I don't know any nuclear strategists who can assure you with 100 percent certainty, that there will be no use of nuclear weapons in a Taiwan scenario, or even in a South China Sea scenario, or let's say an East China Sea -Senkaku scenario.

Lyle Goldstein (12:17):

I also work on the Korean peninsula a lot, and this is also a powder keg. And that's one in which, you know, millions could die in the first 24 hours. So all of these conflict scenarios are you know, not to be too crude, but one can say that they make the Iraq war, the war in Afghanistan, like a look like a tea party. I mean, and those have been tragic and have caused a lot of suffering and death, but these are of a magnitude that's much more similar to a World War I, World War II, that kind of terrible, catastrophic impact. And you know, another thing to consider is you know, just as the rise of Germany brought about, as we all know, a series of wars, right? One can consider that it’s a possibility with U.S.-China interaction too; that is, there could be the first major war.

Lyle Goldstein (13:13):

Then there could be the second war after that. So, I mean, we need to be mature and responsible here and not, you know, light the embers and pour gasoline all over this. We need to take responsible steps, which are toward compromise. So you know, I come at this, I have a lot of passion on this subject, precisely because I am looking at the you know, what I think are very dark possibilities. You know, it's been said that you have to, in order to prevent a tragedy, you have to envision the tragedy. And I'm afraid to say that, you know, I can see it and we need to avoid that future. And, you know, we cannot wait for the crisis to come, because in the crisis, you know, leaders are often irrational. There's, you know, the public opinion is easily swayed. There's a rally around the flag effect there. We have to take steps before the crisis to prevent, you know, to head off this kind of train wreck.

Helena Cobban (14:18):

Thank you for that. Great reminder. I mean, I think another thing that we need to do is to broaden the understanding. I mean, you know, I think it's really remarkable that there is somebody like you at the U.S. Naval War College, and I'm sure that you know, well next week, just to give a little teaser here, we're going to have Dr. Michael Swaine speaking in dialogue. And there are a number of other specialists on strategic affairs who look at the whole picture as you guys do, who understand, you know, the lessons from the two so-called World Wars which ended with Hiroshima, but this time we're talking about a potential world war in which nuclear weapons exist, I mean, from the get go. So it is a very sobering thing for the public to understand. I mean, what I am eager to do with our project here from Just World Educational is to broaden the public understanding of these issues, because there is so much kind of xenophobic or jingoistic mobilization going on in this election period.

Helena Cobban (15:31):

I want to come back to, as a sort of focus back toward your cooperation spirals matter, but before that, your book went to press, I guess in 2014 or 2015, I can see that it was before the JCPOA on the Iran issue, because that did change a lot of things. But a lot has changed since your book went to press. So while I really value your, kind of your idea that we need to look at things calmly and to find de-escalation steps, are there specific cooperation spirals, you lay out in your book - would you be able to update them? Is there still a possibility on these different issues, like the South China Sea or the Middle East or you know, global governance, or the many issues that you do cover in your book? Could you update those spirals?

Lyle Goldstein (16:42):

Well, Helena, of course I would be very pleased to update them and perhaps I should. You're inspiring me - maybe I should consider, you know, a full-up revision of the book and make some new suggestions. But I would say, probably 80% of the proposals probably would still hold today. They - it involves, you know, in every situation, you know, and, and, if you get a look at the book, you'll see that I have really gone around the compass. That is, you know, I have a whole chapter on Taiwan and of course that's the issue du jour. You know, I think, unfortunately we're all too close to a conflict over Taiwan. But I think that one, that spiral, I think, does hold up today quite well. I looked at the South China Sea and Korea very carefully.

Lyle Goldstein (17:44):

And those spirals I think are, are in pretty good shape if we were to enact some of these ideas and then, but I also made an effort to reach out to the different areas, including for example, South Asia, the Indian Ocean and how China's relationship with India is absolutely critical to the 21st century and the 22nd century, as India continues to rise. You know, maybe that chapter is even more important than I thought. And since we're seeing a lot of China-India tension, which I think is very dangerous, you know, I been asked occasionally, well, what did you leave out?

Well, I didn't, there's no chapter there on the Arctic, for example and you know, actually, next week I'm giving a lecture on China’s strategy in the Arctic. So, I mean, there are things that are just not in this book, but we, you know, look, the basic formulation, is that we want, you know, we have certain asks of China. We want them to do certain things. We want them to be a responsible stakeholder. We want them to not push around their neighbors, you know, hopefully to abide by international law. We want them to do all these things, but in my view, we were going to need to extend a hand, which is, I think again, intuitive to most people as how cooperation works. And, and we need to a show China our goodwill and that may involve reducing U.S. presence or trying to act in a cooperative way in certain very sensitive areas. And we have not done that. We've done really opposite partly, and by the way, this, this isn't just a result of of the present Trump administration.

Lyle Goldstein (19:42):

You may recall a lot of the tension actually began, and one reason I decided to write the book, was the Obama administration had enacted the so-called “pivot,” the rebalancing to Asia. And then really that, I mean, although things could, there was some tension before that, of course going all the way back to the EP-3 incident in 2001, and so forth. But really that was a moment where, you know, in my view, the region began to slip into a very, really what we must call a kind of hot rivalry with some dangerous crises, for example, the Scarborough Shoal crisis in 2012, that could have easily escalated, and a lot of deployments since then. So anyway, you know, it's a difficult enterprise. How do you pull two sides back from the brink?

Lyle Goldstein (20:42):

And I like maps and, and you know, as a military analyst, I tend to focus on deployments of forces and so forth. And I consider myself a realist. So for me, actions and forces are much more important than words. You know, one can say all day, I would like to meet China halfway, you know, and have nice pictures of people clinking glasses, and so forth. To me as a realist, you know, that doesn't mean very much. It's, you know, it's useful, summitry and so forth. I applaud that, but I would like to see concrete outcomes, reductions of forces, forces moving into a disposition that's more peaceful and less threatening. To me that that's real change, solid change.

Helena Cobban (21:22):

And also, sort of force deployments that are not hair-trigger, you know, where you build in time -

Lyle Goldstein (21:32):

Yeah. Forces that are defensively oriented and have different doctrines. And we can do that. I mean, there's a lot of scholars who spent a lot of time thinking about what forces are more destabilizing

Helena Cobban (21:43):

And a lot of experience from the end of the U.S.-Soviet Cold War in doing precisely this.

Lyle Goldstein (21:49):

Exactly. In fact, one of the now that you raise that Helena, I think I will just relay a quick story from one of my last trips to China, where I was asked by a Chinese scholar about the so-called CFE agreement in Europe, that was the Conventional Forces Europe. And that, you know, to those of us who remember how the cold war ended in Europe, that agreement was absolutely pivotal. I mean, that was the one that really pulled the Russian – Soviet - army back. And that made it into, what was viewed as a very threatening force into something much more, that had a reliable disposition that was going to be defensive. And it counted things like tanks and helicopters and artillery systems, but it put them in certain areas, you know, reserve areas far away from the front line.

And, you know, that is a classic confidence building measure, by the way, you know, sad news on that front, that agreement fell apart about 10 years ago, when the Russians said, we're finished with this. We don't want to, we're not going to play by these rules anymore, because you know, NATO hasn't played by those rules.

So, anyway, this Chinese scholar was saying, why don't we apply this to the Asia Pacific? Why can't we come to an agreement about force dispositions to do this in a peaceful way? And I, you know, it still echoes in my head because I think that was a fantastic idea. I didn't - that was after I had written the book, so I didn't manage to work it in, but what a great idea. And then by the way, that's one reason, Helena that I'm always reading Chinese sources so carefully, because they do have a lot of great ideas for reducing tension.

Lyle Goldstein (23:24):

They don't want this cold war. They certainly don't want a hot war. And you know, in my view, we need to take Chinese voices very seriously. So I'm trying to do that with my work. But one last thing I want to say here Helena, is that the enterprise of pulling the two forces apart is especially difficult. Partly because, I mean, the fact of, you know, it's more or less just a result of history that the United States has large forces very proximate to Chinese borders. Right? We have forces in Japan. We have forces in Korea. We did have forces in Taiwan, but we have forces that are ready to go near the South China Sea and so forth. These are all areas near China, which make, which unnerve, the Chinese a lot. Okay. Let's face it. Their Chinese feel like they're hemmed in or ringed by U.S. bases.

Lyle Goldstein (24:13):

Well, China doesn't, you know, they don't have a base in Cuba, or a base in Venezuela or a base in Mexico or Canada or something like that. And if they did actually, it would actually make the enterprise easier, right? Because, you know, we would pull a base out of one area and they'd pull a base out of, whatever, Mexico or something like that. So in a way, the asymmetry of the dispositions of the two military forces makes this actually quite a bit more difficult. And so, but we have that, that invites us to be creative about how we do this.

Helena Cobban (24:47):

Yeah. I mean, just building on what you said, the Cuban missile crisis was resolved in the end or quite speedily, depending how you look at it, because the U.S. was, had been planning to deploy certain things in Turkey and, you know, so there was a deal to be made, because Turkey is very close to the Soviet Union, the former Soviet Union’s southern border. So they agreed not to do that. And the Russians agreed not to deploy the missiles in Cuba. So that was, in a sense -

Lyle Goldstein (25:21):

Like a certain symmetry, a certain elegant symmetry to that solution to crisis.

Helena Cobban (25:25):

But also to the relationship in general, I mean, you know, by the time you got serious arms control negotiations and agreements happening in the sixties and seventies, between the U.S. and the Soviet Union, there was a sort of recognition that these were the two superpowers, and that's how everybody spoke about it. And, but there is not that recognition of a kind of superpower equality between China and the United States, right?

Lyle Goldstein (25:55):

And I, by the way for interested audience listeners, I have no doubt that China is a superpower. If you look in this September 2020, one of the issues of “The Economist,” they have an analysis that suggests China's economy in 2019 is, is something like 19% larger than the U.S. economy. So in my view, we need to recognize China as a superpower, but you're right. Most strategists do not. And there is that asymmetry that again, causes difficulties, if you will. And, you know, if one wants to look upon this relationship hopefully, you might say, well, as China matures, as it grows, as it becomes stronger, you have a more equivalent balance of power. And that may result in a greater symmetry that allows kind of more people to see this more clearly and develop more compromises. On the other hand, though, that that can be obviously a much more dangerous situation.

Lyle Goldstein (26:50):

We don't want to rerun the Cuban missile crisis five times and, you know, just hope that it ends well, because that was extraordinarily dangerous. I mean, I've been involved in some of the historiography around that, and I actually got to interview a Russian submarine captain who was down there in the Caribbean with his finger on a nuclear trigger. And you know, the Americans didn't even know that, that the Russians had deployed nuclear torpedoes on board, these submarines. So there's so many uncertainties here and the dangers are such that we really need to act now to head off some of these dangers.

Helena Cobban (27:24):

I guess a kind of concomitant threat is what's called the Thucydides trap, which is where you have this handover of power from, I guess in those days, it was Athens to Sparta or vice versa. I forget, but you know, and the declining power becomes so edgy that they launch foolish wars to try to preserve their power and to depress the rise of the rising power. And it doesn't turn out well. I think that's the short version of the Thucydides trap.

Lyle Goldstein (27:59):

Precisely. And I think Graham Allison also would be very pleased with your summary. I credit Allison with a huge insight here. He really brought our attention to this. And you wouldn't be surprised that his book and mine sort of work well together, because we're worried about the same phenomenon that he seems see clearly, but, but as you point out, Thucydides, got to give him some credit too, he saw that one of the interesting phenomena here was that it was the fear. It wasn't just the growth of power because, you know, people say, well, rising China, that's the problem. It's also the fear of a rising China. And that's the key insight from Thucydides and the Thucydides trap, as it were, now. The good news, thanks to Allison, I think a lot of people, including in China, are discussing this. And so that's the good news, but the bad news of course, is the last several years have seen such a dark turn, part of going back to what you were saying earlier, this turn towards xenophobia, jingoism, you know, a just kind of uninformed set of accusations across the board bordering on, I think, racism so, you know, smart people, scholars have to, we have to fight back against this. That's very disturbing.

Helena Cobban (29:14):

So right now we can go two ways in the discussion. One is, we could jump into one of your spiral areas and just talk through, you know, Taiwan or the South China Sea, or the other way we could look forward and say, you know, in January, let's hope we will have a settled election and a president will be around for four years. We don't know who it will be. But what would be the three main asks? So should we do that or should we dive into one of your spirals?

Lyle Goldstein (29:49):

Well, I guess, having put the work in on the spirals and not knowing who the next president is. I wouldn't want to guess the future. So I probably will, maybe should, stick with the spirals, but I mean, I certainly I'm hopeful that, whoever is the next president that there is a rethinking of China policy. Hopefully we've reached the nadir, and that we'll be headed in a positive direction. I don't think it can get much worse than we're at right now. I can tell you as somebody, I watch Chinese military news every night and monitor the Chinese military press and the Chinese press in general. And I'll tell you, it is, it is very dark and foreboding. And you know, there is a lot of suggestion of, you know, I'll just give you an example.

Lyle Goldstein (30:39):

There was a piece by Hu Le, who was at their Academy of Military Sciences, and he published it last week and the thesis was, you know, China was brave enough to fight the Korean war, even though they were at a huge disadvantage. So he's basically saying, well, China's much stronger now. So, do we fear, or do we dare? Do we dare to fight? And he was basically urging his compatriots to dare to fight, to dare to stand up against the United States, so that, you know, that to me, this is a really disturbing kind of take.

And as you pointed out, very astutely Helena before that, that Americans seem completely unaware of this. And I don't know why that is because, you know, it's been quite clear. I mean, there've been a couple of articles, but I mean, to me, if superpowers are girding for war, that's front page news, you know, and unfortunately we seem to be sleepwalking into this conflict. So, anyway, perhaps we talk some spirals.

Helena Cobban (31:46):

No, that's great. Thanks. That's great, so if we were looking at, as you said, the Taiwan issue, which is the current, as you said, issue du jour, where a lot of recent developments seem to, including our government's increasing support for a sort of move toward Taiwanese independence, which breaks the norm that has existed in both Taiwan and in mainland China since 1949, that they are one country. Now it's a question which, which, you know, whether it was the KMT or the Communist Party, which rules the country, but there was such a strong agreement amongst those two sides that there should be no secession, but now secession seems to maybe be on the agenda and supported by some political forces in this country.

Lyle Goldstein (32:45):

Yeah. And I would, and maybe I'll put up this spiral that I developed for Taiwan, so you can have a look at it. But I'll just say by way of introduction to the Taiwan issue, and I really urge Americans and other people in the West to grapple with the history, right. I mean, it didn’t – the U.S. – Taiwan - China triangle, if you want to call it that, didn't start in 79, you know, go back and look at Roosevelt’s statement on it, look at Truman's statement on it. You try to understand the evolution of U.S. policy, because it really has taken some interesting swings. But I'm very worried, I think look, you're right that some of, some of Washington's predispositions to kind of lean toward Taiwan, I think, you know, with these recent visits by two cabinet level appointments have been escalatory and dangerous for sure.

Lyle Goldstein (33:42):

I don't, you know, to me, it was unwise to, I think we sank a $250 million into a new facility that sure looks like an embassy in Taipei. Again, very unwise if it's not an embassy, it sure doesn't, you know, merit $250 million. I don't, by the way, I don't know what building in another country would merit all that taxpayer money myself. But anyway, we have done it. A missile defense shield or something, but to my reckoning that's, you're not behaving consistent with a One China principle, if you are building a giant embassy in Taipei. Now of course, that has China very upset that it seems like we're breaking out of the, as it were, the kind of agreement more or less going back to the Kissinger-Nixon days where we set this relationship up. After all, when, by the way, when Kissinger arrived in Beijing for his secret meeting in 1971, he spent more than half the time talking with Zhou En-lai about Taiwan because Taiwan was the big barrier, and it still is, in the relationship.

Lyle Goldstein (34:55):

So but I would also say that the Hong Kong issue has really turned the tables on this. And that really is in a way, is what has gotten the region so, turned it into such a bitter debate and a lot of people in Taiwan scratching their head going, we don't want to be like Hong Kong. And a lot of people thinking that the solution that Deng Xiaoping, the brilliant, frankly, in my opinion, brilliant compromise that Deng Xiaoping had come up with, that they called one country, two systems, a compromise, right? Two systems, meaning your system coexists with my system within one country. That that was a brilliant compromise, but now people are saying that that's dead, but let me show you my spiral here. And we can consider whether it is still viable.

I can walk you through a few steps here, but more or less, it starts at the bottom. And I do argue in the book that the U.S. should start these, by and large, should begin these spirals, partly because the U.S. is, is kind of recognized the stronger power, which I think is generally true. Speaking holistically at least. And you know, one may say that this idea of reduction of forces on Guam as a first step is a bit you know, some may call it quaint now or something like that. But to me Guam has been a center, where we have put a lot of military eggs in that basket. You know, we've kind of pushed as many forces as we can onto that island, that one island. And to me, by the way, just at a military strategy point of view, that's quite foolish, right? I mean, the Chinese can target it and it kind of invited them to target it, by putting all our eggs in that basket. To me, we could reduce some on Guam and frankly, the people in Guam would be very thankful.

Helena Cobban (36:55):

So that is the, the first U.S. step in this, reciprocated by what you call PRC one there, the first Chinese step.

Lyle Goldstein (37:04):

Right. And in PRC one, I advocate that the Taiwan and the mainland undertake military exchanges without preconditions, they've had actually military exchanges in the past, but they have you know, lately I think actually the mainland side has really put some preconditions on there. And so maybe mainland could reciprocate by taking off those preconditions and initiating those talks. Because I think that would help lower tensions. And by the way, that would be very appropriate in current circumstances where you literally have Taiwan and mainland pilots facing off every day above this rate. I mean, that's a very dangerous situation if there's an accident.

Helena Cobban (37:49):

So they don't have a hotline?

Lyle Goldstein (37:52):

I'm not aware of one. But yeah, there's, I mean, look, there have been talks over the years between the two militaries, but they started really on the coast guard side to be frank.

Helena Cobban (38:04)

So, that's good. I mean, anything is better than nothing. I mean, as we all know, with Iranian and U.S. forces in the Gulf, which is a very, you know, tight area, you just have to hope that they have a military to military hotline to avoid problems, you know?

Lyle Goldstein (39:21):

Yeah exactly. I mean, that's, you know, there are, I dare say Helena, there was even a set of discussions also last week in the Chinese press where they were saying, you know, who's willing to shoot first and the Chinese side on a lot of, the South China Sea and several issues were actually saying that they had a doctrine, they would not, they would never, shoot first. And the Taiwanese also recently announced that they kind of have this doctrine too. They will not start shooting, but then again, it is very good. It's very encouraging, but now you have some mainland voices, some of whom I know actually, strategists coming out and saying, no, you know, this is not appropriate for a great power. We will shoot first. And you know, we need to revise this doctrine. It's not appropriate for the Taiwan situation.

Lyle Goldstein (39:09):

So, you know, we don't want to hang our hat on it. Anyway, the U.S. move two would be to close the military office of the Institute in Taiwan. That's that glittering the $250 million facility, which I'm afraid does have quite an active military office, right. Because they're moving billions of dollars of equipment. So I think that should be closed. And that would be a very powerful signal to the Chinese side. And the Chinese could reciprocate for PRC two, I advocate that they move the missiles back. And they're, you know, again, I’ve been criticized. People will say, well, you know, the missiles, if they're moved back, they can just be moved forward. You're not eliminating the missiles. I agree, but actually the movement of missiles and where they are positioned initially, it does matter a great deal actually for a military scenario. So that's not a small thing. And by the way, Chinese negotiators have put that on the table. Before, at Crawford with Bush, they actually discussed the disposition of missiles in the East China area.

Helena Cobban (40:10):

Interesting, so is that a verifiable move? I mean, you could see them doing it. And then you could see if there was any, like the missiles creep back to where they were.

Lyle Goldstein (40:22):

Yes.. I think that would be exactly. Yeah. I think you're right. Look, there are limits to that. I mean, China has an awful lot of caves and, and they, China is quite expert at moving military systems around without anybody seeing. So I don't want to oversell that, but I do think it would be - look there, we're talking about thousands of mobile missile systems, not just ballistic, but also cruise missiles. And we could verify movement of a number of systems. Again, that would be a powerful signal to Taiwan that they're not looking to invade Taiwan tomorrow. Now, then as U.S. step three, I advocated for a halt to new type weapons that is, you know, enough with the rolling out the latest. And by the way, a lot of Americans had gotten very wealthy off this this situation.

Lyle Goldstein (41:10):

But I think it has to stop and, you know, so we could start by halting new type sales. So that is at least for a period, we continue with the old type sales, but we don't need new weapons. And then PRC reciprocal move number three would endorse a more robust Taiwan presence internationally. And I think there, you know, there's a huge scope for Taiwan to play a role on the world stage, but mainland would need to kind of endorse this and, and may even could even, you can imagine even them assisting this and welcoming this actually, but it would have to be part of this spiral, right? I mean, right now we know they're extremely hostile to any kind of Taiwan presence on the world stage.

Helena Cobban (42:01):

You know, I want just for time reasons to lead to the end of this, but people will need to go to our website or go to where we will be publishing the whole of this. And the kind of the end goal here is your PRC five step, which is undertake final stage negotiations, including provisions for no use of force, as well as no PLA and no CCP, so that's no mainland Chinese military or political presence on Taiwan. That was the kind of in a sense, your goal.

Lyle Goldstein (42:39):

Yeah. I mean, I talk about final status negotiations and by the way, Helena, I mean, almost everybody who thinks about this really seriously comes to conclusion that the only solution is a kind of confederation solution, which is essentially one country, two systems, more or less dressed up in some nice language. I agree with that. And I think that would be part of the final status negotiations, but I also include in that a military aspect, which is that China would restrict its growth of amphibious warfare capabilities. That, and to me, that's what Taiwa fears the most, you know, that more than anything else, they don't want to see a landing and you know, hundreds of thousands of Chinese troops all over the island. So if China were to visibly restrict its capabilities in this area, that would be a huge symbol. And I think they could do that, but by the way, they're doing the opposite right now, they're building amphibious warfare ships like crazy, like sausages.

Lyle Goldstein (43:34):

So, you know, China, you know, also should recognize that it can take certain steps here and then, as you said, the final status, you were saying, I don't think it's that hard because the mainland has agreed. I'm going back all the way again, to Deng Xiaoping, who said, you know, we are not going to put, we do not intend to put, CCP personnel or PLA, you know, Chinese military on Taiwan. I mean, that's, you know, I think that that offer still holds. So, I mean, that's quite tremendous and we should take them up on it. And by the way, again, the idea that this is crazy or outlandish, I think is wrong. Look, the leader of Taiwan Ma Ying-jeou, and Xi Jinping met in 2015. So they were sitting at a table, you know, so it's not that it's not crazy in my view to consider that the two sides would negotiate this out and that the U.S. could kind of gently nudge Taiwan along and help here and there. So, so yeah, this is what I see. And I think a lot of these ideas still could be useful in deescalating.

Helena Cobban (44:43):

Well, thank you so much. I really appreciate your willingness to dive into this with me and with our audience, because, you know, you say your ideas for de-escalation are not crazy and they are far less crazy than the idea of escalation and nuclear war. I mean, let's keep that in mind. So, you know, I think it's great that you have these very concrete kind of steps that people can take. And I hope that many more people here in Washington, DC, and in every congressional district start to take this idea seriously that we don't have to have an escalation with China. So Lyle Goldstein, thank you very much for being with us today. This has been a great way for us to launch Phase II.

Lyle Goldstein (45:32):

Thank you so much, Helena. I really enjoyed talking with you and your audience.

Further Resources

Speakers for the Session

Dr. Lyle Goldstein

Helena Cobban

Support Just World Educational

JWE has a golden opportunity to make a difference in this country...

Stay in touch! Sign up for our newsletter: