This Online Learning Hub presents multimedia records of the six public conversations that Just World Ed presented in June 2022, in order to engage new generations of Americans on the topics of:

- nuclear risks and realities;

- the nuclear-weapons underpinnings of world order and geopolitics in the 21st century; and

- the possibilities opened by the 2017 Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW.)

These conversations were co-hosted by JWE President Helena Cobban and Project Manager Amelle Zeroug, and involved the six expert guests shown in the list to the right.

In this hub, we present:

- links to the video and audio records of the five webinar sessions we presented in this series,

- the link to the audio of the “Twitter Space” (audio-only) conversation we had with Ted Postol,

- short digests of each of the conversations, and

- links to a broad fund of resources that can help interested individuals to dig deeper into these issues.

- a pamphlet on nuclear risks available for download here.

We’re planning to use these materials and others as building blocks in a follow-on project to create a more intentionally designed, web-based curriculum on “Nuclear Realities 101″. If you’d like to be involved with this project, please contact Amelle Zeroug: Amelle@justworldbooks.com.

- Ivana Hughes on the health effects of nuclear testing & uranium mining

- Vicki Elson on the TPNW and Nuclear-Ban basics

- Joseph Gerson on Nuclear Weapons-Free Zones and the TPNW

- William Quandt on Israel’s nuclear arsenal and its political impact

- Ray McGovern on earlier strategic arms-control arrangements and their erosion

- Ted Postol on nuclear history and nuclear risks

Click-through link to:

- Additional resources (to come)

Ivana Nikolic Hughes on the effects of nuclear weapons & their testing

Dr. Ivana Nikolic Hughes is the incoming (Summer 2022) President of the Nuclear Age Peace Foundation (NAPF). She spoke with us June 15. The full 73-minute video of our conversation is here, and an audio-only version is here.

Hughes has spent 13 years as a chemistry professor at Columbia University, where she directed the K=1 Project, Center for Nuclear Studies. She earlier won her BS in chemical engineering from Caltech, and a Ph.D. in biochemistry from Stanford.

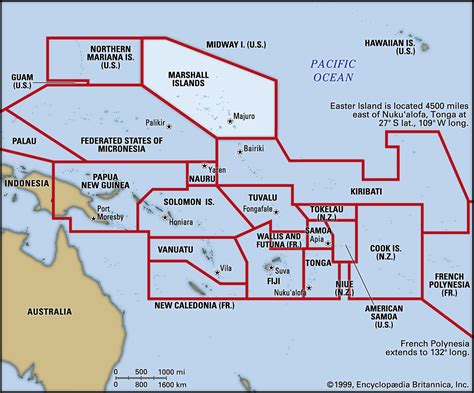

One of the key projects she has pursued at Columbia has been to lead study groups of students and researchers to assess the longterm effects on the people of the Marshall Islands–which includes the infamous Bikini Atoll–of the nuclear weapons testing that the U.S. government conducted there from 1946 through 1958. She and her students and colleagues visited the islands twice, to document the lengthy physiological, societal, and other longterm effects of that testing, and to hear from the Marshallese leaders what they felt they needed to make reparations for that damage.

When she spoke with us June 15, Hughes was just on her way to Vienna to attend the first-ever Meeting of States Parties to the 2017 Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW.) In her conversation,she focused on the effects that nuclear-weapons testing, primarily by the United States but also by Britain, France, and the former Soviet Union has had on the populations and eco-systems of the places in the global South in which they carried out those tests. (She started listing those locations at 36:07 in the video.)

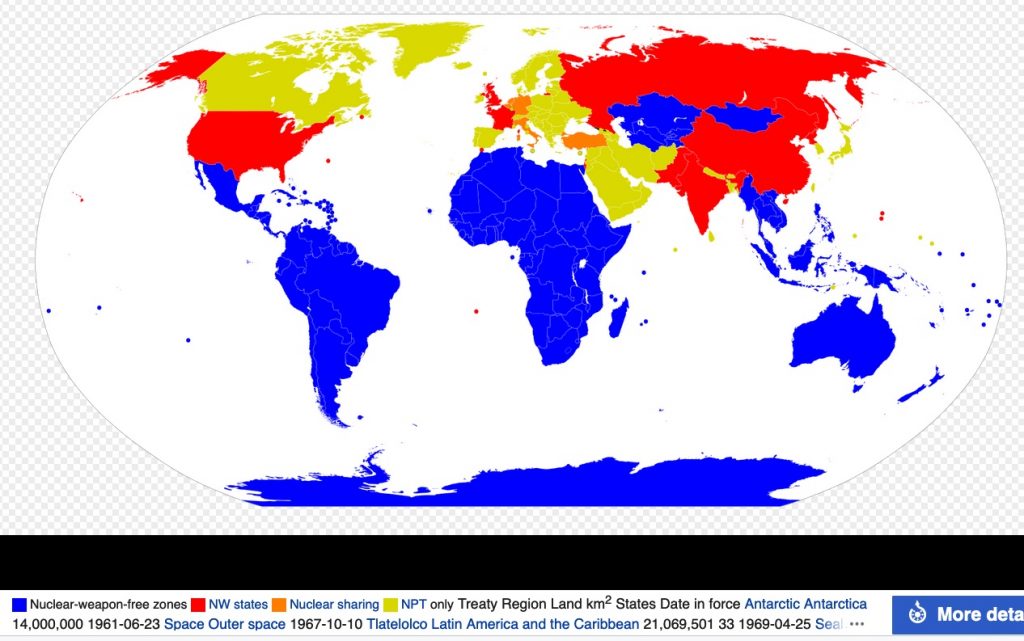

She explored how the countries that carried out those tests might provide some measure of “accountability” to the peoples of the affected zones (31:40). She explained her strong judgment that the 1968 Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) has not met the needs of that vast majority of states that do not have nuclear weapons, and the relationship between, and the relationship between that effort and the TPNW– starting at 42:40.

Here is a key part of her opening presentation (starts at 10:42):

As I assume everyone on the call knows, the United States tested one weapon in July of 1945 and then used two weapons in attacks on Hiroshima, Nagasaki, August 6th and August 9th. Absolutely devastating events. And these attacks killed on the order of 100,000 people in each of the two cities and literally just flattened the two cities. Those bombs that were used had an energy yield of 15 kilotons. That’s not the weight of the bomb; it means that you would’ve needed an equivalent of 15 kiloton of chemical explosives to actually get that kind of an explosion. And 15 kilotons is 15 million kilograms of chemical explosives. So you can imagine that that’s a lot of chemical explosive that you would need to cause an equivalent amount of energy.

So this was summer of 1945. The very first test that took place in the Marshall Islands took place July 1st, 1946. So less than a year later United States was ready to test new weapons and continued to do so until 1958: for a period of 12 years. And during that time period, not only did we test bombs that were similar to the Hiroshima/Nagasaki bomb in design, energy yield, and so on, but that energy yield kept going up. And at the same time, we were able to design a new type of bomb called hydrogen bombs where the energy yield just skyrocketed. It was a huge jump in this energy yield. And in fact, the largest bomb that the United States ever tested was the Bravo bomb that was done on March 1st, 1954. It was tested in Bikini Atoll. And it had the energy yield of the equivalent of a thousand Hiroshima bombs.

So you can imagine this was an absolute monster explosion. It produced a mushroom cloud that was 25 miles high. I don’t, I don’t even know how to think of– it’s a scale that’s unconceivable… So this was so big that all of this radioactive material went into the stratosphere and then kind of got sent essentially all around the world. Of course, the fallout and the kind of return of all of that radioactive material was greatest near where the testing was actually conducted. And so the fallout not only affected Bikini Atoll but it also affected other apples where people were living at the time, with absolutely devastating consequences. So I’ll just say one more thing. So Bravo was one of the hydrogen bombs. We tested other hydrogen bombs as well, but for a period of 12 years, it’s as if the US had bombed the Marshall Islands with 1.4 Hiroshima bombs every single day, that’s what actually happened for 12 years, every day, 1.4 Hiroshima bombs. It was absolutely absolutely devastating.

Related resources:

- Great 8-minute video from the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) on the effects of dropping one nuclear bomb on a city

- 1983 movie, “The Day After” (2 hours)

- Wikipedia page about “The Day After”

- Atoms and Ashes: A Global History of Nuclear Disasters, by Serhii Plokhy (2022)

- Wikipedia page on the Marshall Islands

- Ivana Hughes’ 2021 piece in The Diplomat on the effects of testing in the Marshall Islands

- Ivana Hughes et al article on medical effects of RMI testing

- Ivana Hughes on Bikini Atoll after-effects

- Text & signatories of the TPNW on the UN’s website

- Website of the International Committee to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN)

- Articles on the health and environmental impacts of nuclear weapons testing at the major test sites

Graphics:

Vicki Elson on the TPNW and Nuclear-Ban basics

Vicki Elson, who’s the co-founder and Creative Director of the Washington DC-based organization NuclearBan.us, was with us for an hour-long webinar June 11. You can see the whole video of it here, or listen to the audio here. Elson talked about the key event that had brought her to the work of banning nuclear weapons: namely, her presence at the international conference held in 2017 at which 122 states agreed on the text of, and signed, the ground-breaking Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.

During the course of the conversation, Elson shared three short videos (links below.) She talked about the expectations for the then-upcoming First Meeting of States Parties to the TPNW, which came into force in January 2021 after the sixtieth signatory state gave it full ratification.

She gave a strong overview of the impact of nuclear weapons:

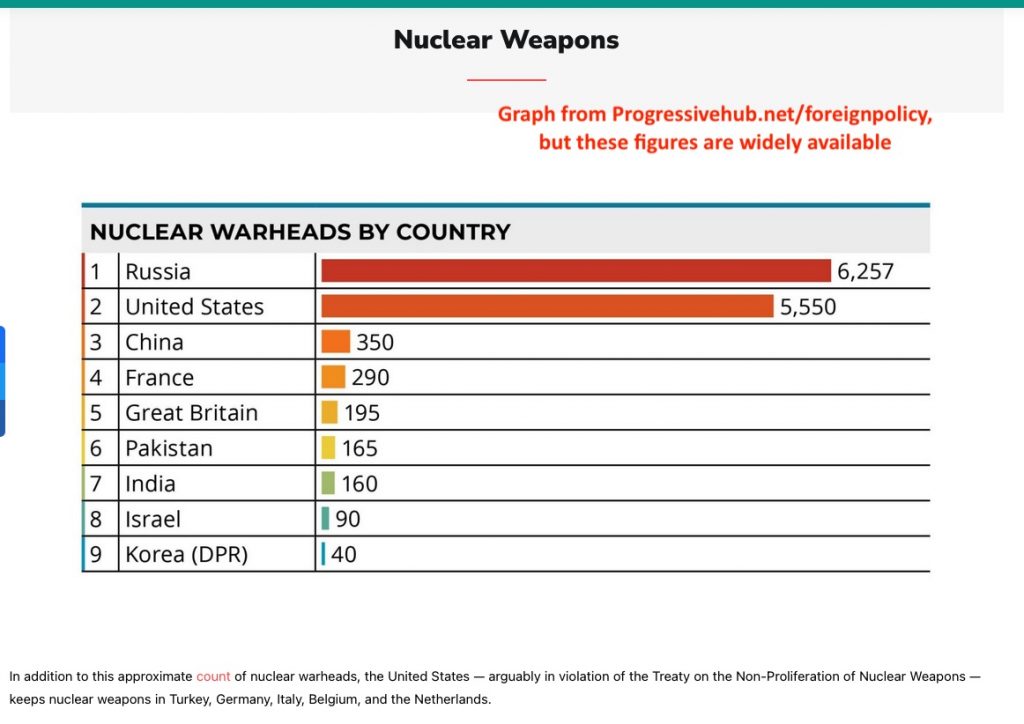

The world knows that 100 nukes exchanged nukes could kick up enough soot to disrupt agriculture and starve 2 billion people. We have 13,000 of them in the world!

The two nuclear bombs the US dropped on Japan in 1945 slaughtered hundreds of thousands of nonwhite civilians. Now they’re much bigger: One nuclear submarine off the coast of, say, Korea, carries weapons 1,280 times more destructive than the one in Hiroshima.

You’ve heard of the Cuban Missile Crisis.. but the world has come within minutes of a nuclear holocaust a dozen times besides that, that we know of. There have been at least 1,000 accidents involving nuclear weapons could have led to nuclear detonation, but (luckily) didn’t. Even so-called “tactical” nuclear weapons are as destructive as the Hiroshima bomb. They just don’t go as far.

Elson listed some of the key differences in TPNW from previous arms-limiting treaties, including that:

- The political momentum for the TPNW came from the whole world, not the nine nuclear-weapons states

- For the first time, nuclear weapons have been deemed illegal in the ratifying countries

- The TPNW outlaws everything to do with nuclear weapons, including acquisition, hosting, or financing them

- It includes provisions for victim assistance and environmental remediation

- The treaty negotiating process began with humanitarian consequences, not politics

- The remaining survivors of the Hiroshima and Nagasakai bombings, known as the Hibakusha, played an important role in pushing for the treaty.

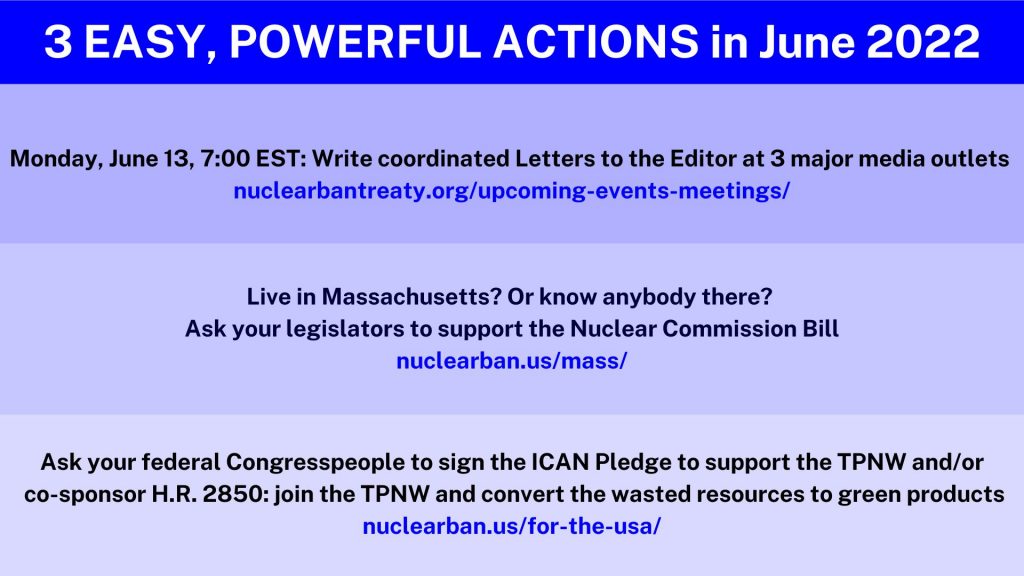

She also provided some very concrete suggestions for how U.S. activists and other citizens can most effectively organize against their (our) country’s continued reliance on nuclear weapons.

Related resources:

- Website of the U.S. Nuclear Ban campaign

- The great FAQs page on the ICAN website

- “To be truly safe” (Vicki’s 1-min. video)

- “The world has spoken: The TPNW is international law” (2-min. video)

- “Fresh Hope: The TPNW, Warheads to Windmills” (6-min. video)

- Info about the existing legislative effort in the U.S. for the banning of nuclear wepons (the “Norton Bill”)

- Global food insecurity and famine due to climate disruption from nuclear war soot injection

- US Conf of Mayors resolution on nukes etc 2022

- ICAN resources for activists & campaigners

- Website of Nuclear Weapons Ban Monitor

Graphics:

Joseph Gerson on Nuclear Weapons-Free Zones and the TPNW

On June 18, our guest was Joseph Gerson, the Executive Director of the Campaign for Peace, Disarmament and Common Security and Vice-President of the International Peace Bureau. Gerson is a veteran anti-nuclear organizer who had just been at meetings in Ulaan Baatar, Mongolia, on the international coordination of Nuclear Weapons-Free Zones. He was with us from Vienna, where he was attending many of the meetings of the Nuclear Ban Week being organized there by the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear weapons, ICAN, in connection with the first-ever meeting of states parties to the TPNW.

You can see the 63-minute video of the session here, and hear the audio version here.

During his conversation with Amelle Zeroug, Gerson addressed a broad range of topics, including:

- How he first became aware of the role of nuclear weapons in global politics (and in U.S. hegemonic practice) during the October 1973 Israeli-Arab war, at the end of which U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger declared a global alert of U.S. nuclear forces.

- How he then became very involved with the movement of Japanese survivors of the U.S. nuclear bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki (the Hibakusha)

- The role of the Russian (and NATO) nuclear arsenals in the current Ukraine crisis.

- The history of the massive nuclear freeze movement of the early 1980s, in the United States: how it was built from the grassroots up and then had a big impact on Pres. Ronald Reagan (starting at 40min32sec)

- Some aspects of the NWFZ gathering he had been attending in Mongolia (18min58sec)

- The differences between the 1968 Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) and the 2017 TPNW, with some observations on how the TPNW got negotiated (starts at 30min50sec)

Here were some details from his description of the historic role played by the nuclear freeze movement of the early 1980s:

I was in meetings where after Randy [Forsberg] had come up with the concept [of calling for a nuclear freeze] and we were talking, how do we take it out more people? We recognize it’s not abolition, but the freeze is necessary step in the direction of abolition. And one of my colleagues, an unsung hero named David McCauley, who was a young organizer in Vermont having learned from something that had taken place in Western Massachusetts said, “I’m gonna take the idea of a nuclear freeze to town meeting.” You know, kind of the mythic origin of American democracy. And he said, “This season 15 towns will vote for the freeze and next year, 175. And we said to ourselves, “Dave, that’s not gonna happen, but go for it.”

And that, that season 17 towns voted for it. There was an op-ed in the New York Times in response to that. In 1982, before the big demonstration in New York, 330 towns and cities across the Northeast, voted for the freeze; eight states and referendums voted for the freeze. And it was that kind of force from below that led Ted Kennedy in the Senate and Ed Markey in the House, if you will, to try to capture leadership with the movement and push it forward. And there were similar kinds of activities taking place across Europe. Unlike now with Putin, we had an enlightened Soviet head of state, Gorbachev, who understood that if there was any chance to save the Soviet economy, he had to stop spending money on nuclear weapons. And there was this, this bringing together… that led to the negotiation of the Intermediate Nuclear Forces agreement (INF), in 1987.Most people don’t understand the cold war ended in 1987 with the negotiation of that treaty. It came before the fall of Berlin wall. It came before the collapse of the Soviet Union, and it came out of popular movements.

Related resources:

- John Hersey’s classic 1946 book Hiroshima

- Wikipedia page about the Hersey book & its impact

- Jospeh Gerson’s 1995 book With Hiroshima Eyes: Atomic War, Nuclear Extortion, and Moral Imagination

- June 2022 Ulaan Baatar statement on NWFZs

- Cornell Univ. web portal to materials on Randy Forsberg & the nuclear freeze movement of the early 1980s

- A 3-min video short “In Our Hands”, with footage from the June 1982 nuclear freeze demo in NYC

- Video of the webinar held to mark the 40th anniv of the June 1982 demo, with Leslie Cagan, Medea Benjamin, Jerry Brown, Katrina vanden Heuvel, David Swanson, et al (2hr16min)

- UN website about the NPT

- Website of Defuse Nuclear War

Graphics:

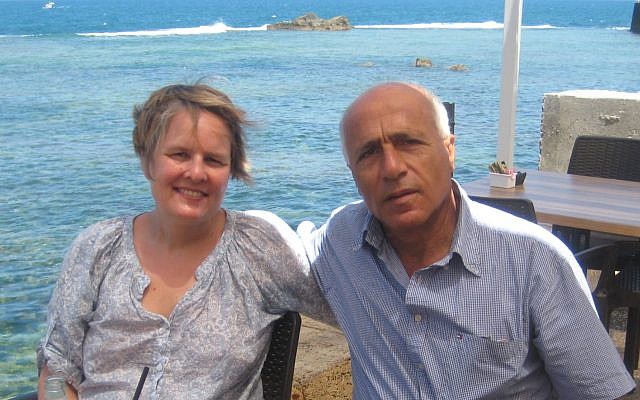

William Quandt on Israel’s nuclear arsenal and its effects

On June 22 our special guest at the session we held on Israel’s role as a key nuclear proliferator. was William B. (“Bill”) Quandt, a veteran Middle East affairs specialist who was the principal Middle East advisor in Pres. Richard Nixon’s White House during the October 1973 Arab-Israeli war and later played the same role in Pres. Jimmy Carter’s White House. JWE Pres. Helena Cobban, who has published a number of articles on Israel’s nuclear arsenal over the years (see links below), was also a resource-person in this session, answering questions put to her by Amelle Zeroug. You can see the video of this session here or hear the audio here.

In the first portion of the conversation, Cobban provided Zeroug with a brief outline of how, from the mid-1950s on, Israel set out– with crucial help from France– to acquire all the knowhow, technology, and materials required to start building its own nuclear arsenal. By 1967, Cobban said, Israel had the means to put together the parts for its first two nuclear weapons; then in 1979, working in collaboration with Apartheid-er South Africa, it conducted a nuclear test from a ship in the South Atlantic, whose fallout was detected by a CIA satellite, the Vela.

Cobban talked a little about the disclosures that Mordechai Vanunu, a whistleblowing former technician in Israel’s secretive Dimona nuclear plant, made to the London Sunday Times in 1986, which revealed the Israeli weapons program to be considerably more sophisticated, broader, and more deadly than had hitherto been known in the West. She also noted that Vanunu’s revelations did not spur any meaningful change of behavior from policymakers and other members of the political elite in Western countries, which by then had a long history of colluding in Israel’s attempts to shroud any mention of its nuclear-weapons programs in a worldwide code of omèrta (silence.)

She said that Israel today has somewhere between 80 and 400 nuclear warheads and several different means to deliver them over very long distances including US-supplied fighter planes, its own Jericho range of missiles, and German-supplied nuclear-capable submarines.

In the second portion of the conversation (at 15:25), Cobban turned to Quandt and asked him how U.S. policy towards Israel’s acquisition of a nuclear arsenal had evolved over time. Starting with Pres. Eisenhower, Quandt noted that in that era the United States did not have any particular alignment with Israel. Eisenhower, he said, had been the president who had pulled the plug on the French-Israeli-British “trilateral” invasion of Egypt in 1956, the action that had spurred both France and Israel to develop their own independent nuclear arsenals. (Britain already had one.)

Then, during the John Kennedy administration, after the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962 one of Kennedy’s main goals was to conclude a global Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT). U.S. intelligence agencies were aware the Israelis were trying to build a nuclear weapons program, so JFK was fairly insistent that he wanted U.S. or international inspectors to be able to inspect what was happening at Dimona.

Kennedy was assassinated in November 1963. President Lyndon B. Johnson, who succeeded him, was much more pro-Israeli than he had been. Under him, the U.S. inspections of Dimona did finally begin, in 1964. Quandt said,

We now know that the Israelis very carefully walled off this significant weapons operation part of Dimona, which was all underground, and those areas were sealed off. So the Americans were allowed to see the benign part of Dimona and they knew that there was no evidence from that, that there was any weapons operation going on. But they also weren’t sure that they were being given full access, which we now know were not.

Johnson was still eager to get the Israelis to join the ongoing NPT negotiations, but he became seriously distracted by the war in Vietnam. By early 1967, Quandt said, the Israelis were close to being able to assemble a nuclear weapon, but “We weren’t sure of that.” He continued:

It has usually been thought that nuclear weapons had nothing to do with the 1967 war. And that is largely true. But the caveat on that is that the Egyptians and probably the Russians, just like us knew that Dimona was more than just a shoe factory or a benign nuclear energy producer and suspected that they were producing nuclear weapons there. The Egyptians had in fact carried out in May just the month before the war broke out in June 1967, had carried out several reconnaissance flights over Dimona. Once they entered Israeli airspace, they could take photographs of Dimona, and they were out of Israeli airspace in three or four minutes and would be over Jordan and then come back and land in Egypt. And so the Israelis could not prevent them from looking at the target and fine-tuning their information about this as a potential target.

So by the middle of May, as the crisis between Egypt and Israel was growing that led eventually to the 1967 war, the Israelis became, I would say almost paranoid that if war happens, the Egyptians are going to strike at Dimona and knowing what they knew about what was at Dimona, this could be very bad for them if it blew up the facility and spread around nuclear material. And so you begin to see in communications, including with the United States– and I have one very important document where the head of Israeli intelligence tells the American head of intelligence that war is probably going to happen soon. And that Israel cannot wait for much longer because they know that if the Egyptians strike first, they will strike at Dimona. And Israel can’t allow that to happen. And he ends by saying, I think within the next couple of days, we’re going to have to act prevent that.

So that, to my mind, is the first indication we have that the presence of nuclear weapons rather than making war less likely makes the Israelis feel they have to preempt so they avoid having their own target hit. And the Egyptians know that there is this target and they’re tempted to strike it. And it raises the temperature in the week or two before the war breaks out on June 6th, 1967 immeasurably. Now, as the war unfolds, nuclear weapons play no role. The Israelis never threatened them. They didn’t really have much in the way of capability and the war was virtually over within the first 48 hours in any case.

Quandt then turned to the Nixon administration. He briefly discussed the Nixon administration’s continuing attempt to persuade Israel to join the now-in-force NPT or at least to provide some other assurances regarding its nuclear ambitions led nowhere. That was the stage in which Israeli leaders tried out the formulation that they have basically used ever since when asked about their nuclear weapons status. Their mantra is simply that they “won’t be the first to introduce nuclear weapons” into the Middle East. All attempts by Nixon-era officials to get the Israelis to clarify what that actually meant similarly led nowhere.

Quandt noted that in Nixon’s early years, his National Security advisor Henry Kissinger had little input into Middle East policy. But in 1972, he started to gain more influence, and the following year he started also serving as Secretary of State.

On October 6, 1973, Egypt’s Pres. Anwar al-Sadat and Syria’s Pres. Hafez al-Asad launched a two-front attack against the Israeli troops positioned since 1967 within their respective national territories, with the primary aim (from Sadat’s perspective) being to jump-start the peacemaking diplomacy that had gotten nowhere since 1967. By that time, Bill Quandt was the lead Arab-Israeli staff person in the White House. He said (at 33:30): “That’s not supposed to happen. You’re not supposed to have non-nuclear powers going to war with a nuclear power.”

He recalled that the Egyptian-Syrian attacks had comes as a complete surprise to the leaders in both Washington and Israel, and added:

In the first couple of days, I think it is fair to say that some highly placed Israelis, particularly the new minister of defense Moshe Dayan, really panicked. He thought, ‘W e are at risk of being overrun’…. There is some reason to believe, although the evidence on this is not crystal clear by any means that Dayan, maybe on the second day or so, proposed in a restricted cabinet meeting to Golda Meir that perhaps the way to stop the Egyptians and the Syrians in their tracks is to do a demonstrative nuclear explosion somewhere, maybe in the Sinai or in the Golan Heights. Not, you know, to destroy troops, but to show we’ve got the bomb and we can use it…

I remember seeing a fragment of intelligence (and I was pretty well plugged in) that said the Israelis had raised the alert status of their missiles and so-called Jericho missiles, which some question whether they were actually operational or they were just sort of showing that they had them. But if they did have them and if they were operational, it made no sense for them to put a conventional warhead on them… But I remember thinking if they’re doing that to get our attention, they got my attention because that means they’re trying to signal that they’ve got a nuclear capability that they could put on a Jericho missile…

I’m still sure that I saw [that fragment of intelligence] and Israelis with whom I have talked who would be in the know, say it probably was a test that was ordered by Dayan, not necessarily by the cabinet, just in case the decision was made to up the ante. And so, that was my first thought that there is a nuclear shadow over this crisis. Very quickly things on the ground turned around. The Israelis were not at an existential threat. The Egyptians crossed the canal, but then they stopped. And so for the next several weeks, there was really no further nuclear shadow as I would call it over this conflict. I didn’t sense it anyway, nobody was making threats or seeming to be alarmed about that.

He also provided (from 37:39 through 42:51) his recollection of the nuclear alert that Kissinger declared for U.S. strategic forces worldwide toward the end of that October, in the context of some intense geopolitical signaling regarding the Arab-Israeli crisis, with the Soviets.

Quandt and Cobban then discussed with Zeroug a number of political issues related to Israel’s possession of a significant nuclear arsenal and the refusal of successive U.S. administrations to do anything to hold them to account for this. These issues included:

- The use Israel has often made of the fact of its nuclear capabilities as a way to blackmail Washington into giving it more, and more advanced “conventional” weapons, so as to prevent it having to rely on or use its nuclear weapons.

- The effect that Israel’s blatant non-compliance with the NPT has had on the credibility both of the global NPT effort and on Washington[‘s credibility as an upholder of NPT norms.

- The hypocrisy of the way in which, in the context of the Middle East, most member of the U.S. political elite, including the corporate media, have blurred public understanding of the especially destructive and destabilizing nature of nuclear weapons by lumping them together with chemical and biological weapons into the catch-all category of “Weapons of Mass Destruction”, making it seem as if the possession by Arab states of, say, chemical weapons is just as dangerous as them possessing nuclear weapons– all the while, usually refusing to even mention Israel’s possession of nuclear weapons.

- The special hypocrisy of the way members of the U.S. political elite fixate (with Israel’s encouragement) on the alleged danger of Iran’s nuclear-technology programs while refusing to even mention Israel’s known possession of a large nuclear arsenal.

Related resources:

A. Articles:

- Wikipedia page on Mordechai Vanunu

- British nuclear expert Frank Barnaby’s 1987 assessment of Vanunu’s evidence on Dimona (PDF)

- Frank Barnaby’s 2004 assessment of Vanunu’s evidence on Dimona (PDF)

- April 2022 Melman article about Vanunu’s eternal imprisonment

- Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists Nuclear Notebook Jan 2022 on Israeli nuclear program

- Jan 2021 AP report on Big Dig at Dimona

- Peter Beinart’s Aug 2021 NYT oped on need for US to be honest about Israel’s nukes

- H. Elbahtimy’s “Diplomacy Under the Nuclear Shadow: Kennedy, Nasser, and Dimona”, June 2022(abstract)

- A Blind Eye to Nuclear Proliferation, by G. Smith & H. Cobban, 1989

- Israel’s Nuclear Game: The U.S. Stake, by H. Cobban, 1988

B. Reports:

- 1999 FAS/USAF report on Israel’s nukes

- US Air Force Ctr-Proliferation Ctr’s 1999 report on Israel’s nukes (a PDF version of the above listing)

- Center for Naval Analysis Report on 1973 War and Nuclear Issues

- Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists assessment of Israel’s Nuclear Weapons, 2021

C. Documents and document collections:

- Kissinger Recommendations to Nixon October 7, 1969

- Helms Memo to LBJ on Amit, 6-2-67

- U.S. National Security Study Memorandum #40 on Isr…

- Collection of M. Vanunu’s photos on Vanunu.com

- Avner Cohen Collection at Wilson Center website*

- Avner Cohen’s online documentation center at GWU-NatSec Archive*

* These last two collections of online documents present the source material on which the very serious Israeli historian Dr. Avner Cohen based his two books, Israel and the Bomb (1998) and The Worst-Kept Secret: Israel’s Bargain with the Bomb (2010). The Wilson Center collection includes links to videos of several interviews Cohen conducted with participants in the Israeli nuclear weapons program, along with transcripts in Hebrew & English, and several oral-history records of interviews he conducted with US officials investigating the 1979 Vela incident.

Graphics:

Ray McGovern on earlier strategic arms-control arrangements & their erosion

On June 8, Amelle Zeroug and Helena Cobban had an 86-minute conversation with Ray McGovern, co-founder of Veteran Intelligence Professionals for Sanity (VIPS). You can find the video of that session, here, and the audio is here.

Before he became a feisty and dedicated peace activist, McGovern had been a Soviet-affairs specialist (and later, head of the Soviet-affairs analytical division) at the CIA. In that capacity, he was very involved in providing the background analysis needed in the US-Soviet negotiations for key Cold War-era arms-control treaties like the Anti Ballistic Missile (ABM) treaty and the Strategic Arms Limitation Treaties, SALT-1 and SALT-2. In our conversation with him, he provided many key insights into the rationale and effectiveness of those treaties. And he lamented the fact that over the past 20 years, the exit of the United States from most of them has left the nuclear-strategic situation between the United States and Russia considerably more fragile than it had been during the last 25 years of the Cold War.

During our conversation, McGovern compared the strategic fragility of the present era with that of the fraught 13-day period of the 1962 Cuban Missile crisis. Scroll on down for a key excerpt from what he said about that.

Here were the other topics he addressed:

- He gave an overview of key US-Soviet arms-control negotiations from the early 1970s through the Reagan era

- He gave a detailed account of the history of the negotiations for the 1972 ABM Treaty (08:21 through 11:40)

- He explained the concern he has about the lack of warning time the Russian have today to discern whether US missile batteries located in Eastern Europe are firing intermediate-range nuclear missiles into Russia (17:47 through 21:34)

- He explained the ties between the current conflict in Ukraine and the U.S. positioning of intermediate-range weapons in Eastern Europe, reviewed the history of the 1987 INF treaty that had barred such deployments, and impact of Pres. Trump allowing it to lapse in 2019 (27:29 through 36:20)

- He noted Pres. Putin’s fury at Washington’s 2015 decision to install missile sites in Romania and Poland, and explained how easily those sites could be converted from using “defensive” missiles to using “offensive” missiles (36:20 through 43:57)

- He called on the publics of the Western countries to wake up to the extreme nuclear dangers of the present situation and to (re-)build a strong anti-nuclear movement ()45:34 through 54:40).

So here, 22:30 through 27:07, was what he said about the Cuban Missile Crisis:

The Cuban missile crisis was in 1962. There was an interesting crisis because the intelligence system the United States had confidently predicted in September of 1962, that the Russians would never, never try to put nuclear ballistic missiles in Cuba. Never. They knew what our reaction would be. They’d never try it, okay? Well, one month later, some of our reconnaissance aircraft, called in those days the U2s, found in photography, Soviet ballistic missiles in Cuba. We very proudly went to president and said, ” We found them they’re there.” And he said, “I thought you told me they–” Well, they’re there. Okay.

So president Kennedy said, okay, what are we gonna do? We can’t take this just lying down. Are they armed? Do they have nuclear warheads on them? And US intelligence confidently said, we assess that there are no nuclear weapons ready to fire on these missiles. Wrong! They were ready to fire. We learned that three decades later. So this gives a little bit of electricity to this whole thing. John Kennedy wasn’t smart enough at that time to say, “What do you mean you assess? Does that mean you guess? Or do you know?” And we would’ve said, well, we don’t know…

Anyhow, he acted very responsibly. Okay. And he said, look, the Russians are trying to create really a strategic danger for us. It’s an existential threat for God’s sake. If they can knock out our naval bases on the east coast and, and blow up our cities– we gotta get rid of these things. And in a very adroit way, he and Krushchev, who was the [Communist] party head at the time in Moscow, worked out an arrangement where there would be a quid pro quo, the missiles would be taken out of Cuba. And we would take missiles out of Turkey. A nice sensible arrangement.

Now, why do I mention that? I mention that because right after, well, just in the middle of these discussions, there was a Soviet submarine near Cuba. Okay. And they had nuclear torpedoes and they were armed. Okay. They were out of communication with Moscow for about four days. They knew that the balloon was up. They had to assume that they lost the war, okay? And so two captains on this Soviet submarine said, well, you know, “Use them or lose them! At least if we’re gonna go down, let’s take five or six US ships in the Caribbean here down with us. Let’s shoot those torpedoes off!” Okay. And they’re already to switch the key when they’re, “Oh, wait a second. There’s the political naval captain here. We have to get his okay.”

In other words, the Russians insisted that they would have a [Communist] party guy and also a captain, and he would be necessary to turn the switch. His name was Arkhipov, okay. And he said, “Do you have orders from Moscow?” And they said, “No, but the war’s lost. We figured it out.” He said, “You don’t have orders from Moscow, you don’t shoot those missiles. You surface!”

They surfaced. And they find out that there was no war, that people have come to this agreement. And that’s how close we came. In other words, if that would’ve started a nuclear exchange, for sure. That was right at the very end of the Cuban missile crisis.

Now let me say just one more time that the kind of missiles… in place in Poland, Romania, and God forbid, Ukraine pose an existential threat to Putin’s Russia. It’s the same deal. It’s the kind of thing that no president of any country can tolerate being right under the gun of medium range and other ballistic missiles. So when Putin’s looking at this, he knows about the Cuban missile crisis and he knows how we reacted. And I think he probably says, you know, why can’t they understand that I react the same way to the emplacement of missiles right on Russia’s border?

Related resources:

- Jeffrey Smith Oct 2021 article on US nuclear upgrades

- Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists Nuclear Notebook on United States Weapons 2022

- 2-26 statement on Ukraine war by international Pugwash

- Michael Klare, 4-20, on New Nuclear era, in Nation

- Video of Nuclear Age Peace Foundation discussion on the nuclear risks of the Ukraine ciris, featuring Richard Falk, Daniel Ellsberg, Noam Chomsky, Cynthia Lazaroff (105-min.)

- Article by Praveeni Swami on NATO’s responsibility for nuclear destabilization in Eastern Europe, March 2022

- Detailed and resource-rich Wikipedia page on the Cuban Missile Crisis

- Robert J. McMahon, The Cold War: A Very Short Introduction (2003)

- Michelle Getchell, The Cuban Missile crisis and the Cold War: A Short History with Documents (2018)

Ted Postol on nuclear history and nuclear risks

Just World Ed launched this project on June 4, with an audio-only conversation that Helena Cobban and Amelle Zeroug co-hosted, featuring nuclear physicist Prof. Theodore Postol. JWE board member Rick Sterling also joined in. You’ll find one brief report about that extremely rich conversation here, and a link to the audio record of it here.

Theodore (“Ted”) Postol is an expert in many aspects of designing nuclear weapons who worked at that task in high positions in the Pentagon before becoming a prof at, first Stanford University and then MIT. Find a longer bio on him here.

In his audio-only conversation with us, Postol discussed many topics related to the history of nuclear weapons, and the risks associated with them:

- He gave an expert comparison of the degree of nuclear risk the world faces today with the risk it faced during the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis (17:04 through 23:55).

- He compared the explosive yield of the current generations of inter-continental ballistic Missiles (ICBMs) with that of the single 12-kiloton bomb that the United States dropped on Hiroshima in 1945, gauging that the explosive yield of the warheads on a single Russian ICBM would be equivalent to between 4,000 and 6,00 Hiroshima bombs (23:55 through 33:59).

- We discussed the scenes of post-nuclear destruction and social breakdown portrayed in the seminal 1983 movie The Day After, and he shared some of the work he did in the mid-1980s on the catastrophic effects of post-nuclear super-fires (33:59 through 39:12; scroll on down to find links to his work.)

- We discussed why the United States and other nations still have nuclear weapons. He noted the promise they give their owners of the ability to coerce other nations and summarized the proliferation of nuclear weapons from the United States to other states (42:14 through 46:49). Scroll down to see an excerpt from this potion.

- He expressed great support for the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons but noted that universalizing it may be complicated (50:56 through 57:05).

- He discussed the impact that the massive nuclear-freeze demonstrations of 1982 and also the Day After movie had had on decision-making in the Pentagon and the Reagan White House (58:25 through 64:19).

- He discussed the effects of nuclear testing (68:13 through 70:15).

- He explained why he sees the United States as a very untrustworthy party to international treaties and decried the unqualified nature of many high-level members of the Biden administration (70:15 through 78:33).

- He explained why he thinks the alarm expressed in some U.S. media over Russia’s development of “hypersonic” missiles is overblown (78:27 through 80:44).

Here is what he said about why nations acquired, and still have, nuclear weapons:

The reason people build nuclear weapons? There are many reasons. First of all when the United States first had nuclear weapons… and nobody else had them (this was only a very short period of time), Americans had the idea nobody else could get them. And we could effectively, you know, coerce the world to do things we wanted to do. I won’t say rule the world, but coerce any country in the world with our nuclear capabilities. Now it became obvious after a relatively short time that… there are all kinds of reasons you might want to coerce a nation and every one of them doesn’t justify destroying the nation in order to coerce them. So people began to realize that conventional military forces were also extremely important.

But there was a time, really almost up to 1960, where the American mentality was that if you had enough nuclear weapons, you can get any country in the world to do anything you wanted. But of course, by 1949 the Russians had demonstrated the ability to build nuclear weapons. And by 1952 or ’53, both the United States and Russians had hydrogen bombs, thermonuclear weapons… The difference between an atomic weapon and a thermonuclear weapon is that a thermonuclear weapon can be of enormous, unlimited yield…

So once the ability to build thermonuclear weapons was available to both Russia and the United States, the political forces for building large arsenals to deter each other from attacking… was a political judgment, just as the French and the Chinese and the British also judged.

The British wanted to be a nuclear weapon state so they could be an independent threat to anybody who bothered them. The United States tried to get them to not build nuclear weapons, tried to offer them the American protection, but the old question comes up: if you were British, would the United States risk being annihilated by Russia if Russia or the Soviet Union at that time destroyed Britain? In other words, would we be willing to retaliate against the Soviet Union and thereby have our nation destroyed in a second response from the Soviet Union? So that the British decided they wanted their own weapons. They didn’t trust that another country would be willing to annihilate itself to protect them. The French of course also made similar decisions.

The Chinese of course, were facing the United States who was constantly rattling a nuclear saber. And they decided, understandably… that in order to get out from under these constant threats of being attacked with nuclear weapons, from the US, that they needed to have a nuclear weapon, to make it clear that if someone tried that against them, particularly the United States, they would kill as many Americans as they could, you know, with retaliation.

So all of these decisions were made based on political judgements. It was a human factor, which is also a very big factor in what could lead to a global nuclear war… The human factors drive people to make decisions that from a broader perspective appear to be very unwise, and they are unwise. But it’s not just the threat that… someone might use nuclear weapons against you. It’s the fact that they might try to politically coerce you… by threatening they will use nuclear weapons against you. That is a big factor that causes political leadership in many countries to decide to build nuclear weapons.

Related resources:

A. Selection of articles by, or interviews with Ted Postol:

- Postol’s chapter on super-fires in 1986 Institute of Medicine study on the effects of nuclear bombns

- Postol’s 2015 artcle on the 1995 Russian-US nuclear scare

- Ted Postol 2019 article in Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists on US violations of the INF treaty under Obama

- Postol 2019 piece in The Nation on US responsibility for the collapse of the INF Treaty

- Scheer interview with Postol in March 2022 w/ transcript & a great cartoon

- Postol in May 2022 on Manifold podcast, 115 minutes

B. Other related resources:

- 2017 BBC documentary on Pres. Truman’s decision to drop the bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki (4min20sec)

- 2020 British Imperial War Museum documentary on Was dropping the bomb on Hiroshima necessary? (7 mins)

- Great video “What if we Nuke a City?” on effect of nuclear bomb, 8 mins

- “The Day After”, full movie

- Wikipedia page about “The Day After“

- “Dr. Strangelove” on Amazon Video

- Best of “Dr Strangelove” compilation (8 mins)