Video and Text Transcript

Transcript of the video:

Helena Cobban (prefatory):

Hullo everybody and welcome to the fourth session of our webinar series "The Ukraine Crisis: Building a Just and Peaceful World." Today, it's Monday March 14, and the primary focus of today's conversation will be the U.S. domestic politics of this crisis and how it affects the peace-and-justice movement here in this country-- a topic that is undoubtedly of great interest both inside and outside the United States. Our three guests today are:

** Erik Sperling, the Executive Director of Just Foreign Policy. He earlier worked as Senior Adviser and Counsel in the offices of Congressman Ro Khanna and Congressman John Conyers. He has a J.D. from Georgetown University Law Center.

** Marcus Stanley, the Advocacy Director of the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft. Prior to joining the Quincy Institute. Marcus earlier spent a decade at Americans for Financial Reform. He has a PhD in public policy from Harvard, with a focus on economics.

** Bill Fletcher, Jr. who is an author and a veteran activist for labor rights, decolonization, and racial justice. He's the former president of TransAfrica Forum; and a Senior Scholar with the Institute for Policy Studies.

Guys, it's wonderful to have you all with us today. And now let me hand over to my co-host here, the distinguished international jurist, Richard Falk. (Richard, You need to unmute.)

Richard Falk (00:00:39):

Thank you, Helena. It's a great pleasure to welcome our three guests. And I think it's appropriate that we turn to the domestic American dimensions of the Ukraine crisis. They seem to me to be very fundamental as to how this crisis can be ended, both in terms of its humanitarian dimensions affecting the people of Ukraine, but also how it is being manipulated geopolitically to create a new kind of geopolitical confrontation. I think these two dimensions are very important to address separately and interactively.

Helena Cobban (00:01:46):

Thank you, Richard. So we are gonna have a short presentation from each of our guests first, and then we'll have a more free flowing conversation amongst all of us here, panelists, at around 45 minutes. We will open this up to Q and A from the from the attendees. People who have questions, please drop them into the Q and A box. And if you have any technical issues or questions, put them in the chat and our project manager, Amelle Zeroug, who is behind the scenes here will answer your questions, your technical questions and any other. She's also dropping a lot of useful information into the chat such as, you know, the participants' bios, because we have three guests today which is unusual for us and wonderful. I'm not going to give everybody like a long extensive bio. You can find that in the chat. So first of all, I'll come to you, Bill Fletcher and ask you your take on the priorities for the peace-and-justice movement globally and here in the United States.

Bill Fletcher, Jr. (00:03:05):

Thank you, Helena. Thank you for the invitation to be on this. And I, I guess what I want to offer are more perhaps framework points and some things to consider. One is to be very clear to begin that we're dealing with, and the principal matter here is one of Russian aggression against Ukraine. And around that there should be no ambivalence. There should be no ambiguity. We're dealing with the, the issue of the failure to recognize the sovereignty of a legitimate national entity, i.e., the Ukraine. And I think that that's important because there certainly among, within progressive forces in the United States there have been those that have been all over the place as to whether there is some justification that can be used for the Russian aggression. And I think we have to be clear, no, there isn't one.

And therefore Ukraine has a right to self-defense. Now, domestically, this is playing out in some very strange ways for a number of reasons. One way that it's not particularly strange is that this invasion much like the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait in 1990 will derail, at least in the immediate, discussions of demilitarization. There will be now a new round of discussions about whether strengthening NATO or new military hardware or whatever in the face of the Russian aggression. And this is something that it seems to me that progressives need to vehemently oppose. It once again, becomes a reason to move resources away from domestic and non-military priorities. And there is no good end to this. The second thing I wanna mention is the question of the domestic right wing. And this is fascinating because over the years Putin has had a growing influence on the domestic right wing.

And this is largely because Putin himself is a white supremacist ,homophobe, repressive, aggressive tyrant, and his arguments about the future of Russia really resonate globally within rightwing populist and neofascist circles. And, and so you have this growing influence of Putin at the same time, the right ended up being split domestically about how to respond to this invasion. And we could see that at least in so-called establishment circles with the attitude of Trump in the beginning, essentially trying to legitimize the Russian invasion, and then you have other forces in the Republican Party, including McConnell and others that have taken a very different stance. And how this split will end up playing out. It is very hard to determine. As we are this discussing before the program started, there are globally rightwing forces that are aligning themselves with fascists within Ukraine.

And so it's, you see this situation of fascists on both sides of this of this battle unfolding over time-- and something that we have to pay a great deal of attention to. I think that the danger of Putin's influence over the right, the far right in the United States is however a really important danger that has been understated and underestimated by forces among progressives in the United States. And there's a tendency to look at Putin's anti-Americanism as being the equivalent of anti-imperialism when it's more equivalent to the Japanese approach, pre-World War Two, which was not anti-imperialist, but anti-west and anti-US, so I'm gonna stop there. There's much, much more to, to be said.

Helena Cobban (00:07:50):

Thank you. That really is a great way to frame things. So thank you. I'll come on to you Marcus Stanley to provide your take on the same subject that is, you know, what are the priorities for the peace-and justice movement globally, and here in the US amidst this current crisis? Also, I gather you've been contacting some people in, in Congress. So if you could tell us what's happening there and give your take on the invitation that I guess has been issued to President Volodymyr Zelensky to come and speak to Congress tomorrow-- not to come, but to appear as he did before the British parliament and the Polish parliament.

Marcus Stanley (00:08:35):

Yeah. So just to give-- he's gonna be appearing on Wednesday-- just to give some framing comments about the crisis as a whole: I think there is this big push that's happening across the political spectrum in the United States, including on the left and some of which was reflected legitimately in some of Bill's comments, to make this sort of about this, this whole issue, sort of about a very black and white confrontation between good and evil, where Putin is evil. And we of course are the defenders of, of democracy and the defenders of the UN charter and Putin is a war monger. And the peace-and-justice movement is against war. This is an aggressive war and a violation of Ukrainian sovereignty that, is inexcusable, I agree with Bill on all of that. And this kind of also plugs into the way Putin has been made of figure in domestic politics through Russiagate and sort of brought into the domestic American political partisanship.

And from that perspective, it becomes very simple. You have an aggressive war monger who has invaded another sovereign nation. The invasion is inexcusable and opposing war means supporting Ukraine's right to self-defense. And one reason that's appealing is, you know, there's significant accuracy in it. It is an inexcusable aggressive invasion. Ukraine does have a right to self-defense. It is a violation of the UN charter and so on. But we are, when we're talking about this from the American perspective, you know, we are Americans, we are not part of the Russian peace movement in Russia which by the way, has been very courageous and deserves a lot of praise. But our question as Americans is what is our own government doing here to either bring peace or to participate or feed into an escalation spiral that create barriers to peace barriers to settling the conflict or escalates the war.

And I would also point out in this situation that the issue with American foreign policy has really never been, that our enemies were good. You know, we're, we're good guys. And, and we were the the bad guys [but not so bad] relative to them. I mean, Saddam Hussein was one of the more, one of the most brutal dictators in the world. I think more brutal with his own people than Putin has been. I think, you know, Ho Chi Minh in Vietnam ... was a dictator as well who violated human rights in many ways. If you go back through these histories of, of what the US has done internationally, it hasn't been the case that the people we lifted up or the people that we opposed were good, guys, that wasn't the issue. It was our own behavior.

So in looking at that, in looking at how we have acted, are acting, and could act, I think that while Putin's actions are inexcusable, I think we have to kind of take it out of that American domestic political context and look at Russia's recent history, you know, the last couple of decades of post-Cold War history in Russia. And there we have in the 1990s, you know, the US succeeded in regime change in Russia, and we actually had significant control there, over Russia's domestic politics, and Russia really collapsed into a kind of corrupt kleptocracy with sort of a fake democracy and Putin emerged out of that. He was actually kind of our selection, as a younger and more vital successor to this alcoholic Yeltsin. So there's a history of US regime change in Russia already that has made, I think, Russia and the Russian people, very wary and suspicious of the US.

And then we have, most relevant to the Ukraine situation, we have decades and decades of warnings about the destabilizing impact of expanding NATO into historical Russian territories, including in particular Ukraine and Georgia. And in spite of those warnings-- which came from very establishment figures, people like William Burns the current head of the CIA warned of this in his 2019 book; George Kennan, one of the architects of the Cold War, warned of the destabilizing impact of expanding NATO, William Perry, you know, I could extend this list. But nevertheless, you know, we expanded NATO in five separate waves, to Russia's border. We doubled the number of NATO members, almost doubled, from 16 to 29. And this year, the crisis really reached an extreme point where basically Russia threw down the gauntlet and said we want the security concerns to be taken seriously, or we are going to, you know, try to bully and use violence to get our way out of this.

And in spite of that, you know, there's varying reports about what we offered during the run up to war. But in spite of that in October, November, we very clearly reaffirmed to Ukraine that-- I don't think anyone thought that in the short term you Ukraine could join NATO, but that in the medium to long term NATO membership was on the table for Ukraine. And of course I think we really did not engage that seriously around some form of military neutrality for Ukraine. I mean, this is, this is something that people are debating about.

But this issue has not disappeared, because when you think about the groundwork for a settlement of this conflict, ever, you know, not just in the short term, but in the medium to longer term as well, any kind of settlement that could prevent the re-militarization of Europe; placing hundreds of thousands of US troops in Europe; massively increasing American defense spending, you know, starting a new Cold War with Russia--

If you think about a settlement that prevents and avoids that then we have to come to grips with these Russian issues about their security concerns on their borders. And these are not simply Putin concerns. These are Russian concerns. They were concerns that were expressed by Gorbachev, by Yeltsin, when Russia was much friendlier to the United States; and they're concerns rooted in Russia's history of being invaded. They have no natural land barriers like the United States does. So you know, these issues, they're a set of issues that are gonna be essential to settling this war. And those issues are Ukrainian neutrality, some form of neutrality for Ukraine, that's enforceable from both sides; the Russian claims over Crimea, which is strategically critical to Russia and which they basically annexed; and the situation in the Donbas where there are many ethnic Russians.

This is the far Eastern corner of Ukraine. There are many ethnic Russians and there was already a civil war where 15,000 people had died at the hands of both Russian separatists and Ukrainian hard liners. So the issue is whether there will be some form of meaningful autonomy or federalization of self government for that area of Ukraine and the Donbas; and these issues are not going away. They will be the center of, you know, either Russia will try to impose settlement on this by force or we will agree to them in sort of an international agreement. And I think one thing for the peace movement to be aware of is, you know, these three things, Ukrainian neutrality, Crimea, and the Donbas, are very compatible with preserving some meaningful sovereignty and freedom for the people of Ukraine. And they're even compatible with Ukrainian economic openness to the west. They're compatible with Ukrainian EU membership. They're compatible with rebuilding Ukraine and Ukraine getting economic assistance from the west. So there, there are possibilities here diplomatically that I think we have to stand for, because if we, if we just are all about, you know, Putin is a war monger, Putin is a demon, and so on, we are preventing any sort of reestablishment of a more peaceful European security order that prevents a new Cold War. And--

Helena Cobban (00:18:15):

Could I just interject?

Marcus Stanley (00:18:17):

I'm sorry. I've got on too long.

Helena Cobban (00:18:19):

No. But, you know, we wanna keep this as a conversation. These were great points, and I think, you know, where you were just then is, is a great summary of what, you know, we all need to talking about. If I could come to you, Erik Sperling of Just Foreign Policy, what do you think are the priorities for the peace movement globally and here in the United States?

Erik Sperling (00:18:39):

Yeah, thank you. I share so much of what, what Bill and Marcus said there. So these are two, you know, tough acts to follow, but I think from our perspective, I think our work of course, there's so many of the activists on this, you know, activists and people who have been involved in this movement for years know, is preventing nuclear war. I think it has to be number one. And I think, you know, we've made some progress on that, Just Foreign Policy, working with groups like Quincy and working with a coalition of of members of Congress on the left and right insisted that, you know, backing president Biden's call to-- his decision to-- keep us troops out. And also we worked to ensure that he actually would pull out troops that were already there. We had hundreds, hundreds of troops there, and that is really a prime opportunity for an unintended escalation, if US troops were to be hit.

And I think it's interesting: on one hand, we do have this role of the far, right, you know, Putin's connection to some of these far right forces in the US, but those are also some of the same forces in the US that have worked with us to oppose things like the war in Yemen and have supported us on constitutional grounds to say, you need congressional authorization to send troops in. So it's just of note, as we worked with Representative DeFazio and Warren Davidson, who's a Republican from that camp... And we had nearly 20 Republicans, which was the most we've had on a letter in a very long time on any issue and very exciting in a certain sense, whatever their motivations are. So we had people from AOC to PaulGosar to Matt Gaetz, to Ilhan Omar and others, all saying, you cannot send troops without congressional approval and you have to pull any troops you have out.

And when that dropped you know, President Biden and the entire, basically all the leadership of the House and Senate and the White House said, yep, there's no chance; we are not sending troops in! So we feel very happy that that has potentially reduced the chance for an unintended escalation attack on US troops. And you know, there's still forces pushing for a no-fly zone to get US troops involved. But we feel that we have a pretty strong group in Congress that'll say you cannot do any of those actions without congressional authorization. And we don't think Congress is likely to authorize those actions because of the great work the peace community, the activists, you know, have done over the years. There isn't a huge appetite for people to wanna be on the record supporting war. They saw Hillary Clinton lost to Barack Obama in large part because of her vote [on the Iraq war].

And so I think that's been a tool that's been really successful, and I'm really happy to see. But it is of note that we are actually working with some of those very, you know, oftentimes very disturbing, you know, people may disagree with them strongly on other issues, but they are with us in terms of insisting that only Congress can choose to send troops in. So I think that's of note. I think, you know, our organization Just Foreign Policy and I think more broadly, the American people-- you know, I feel like our duty, I think Marcus said this as well, is to focus on what we can do as Americans, what our government can do to promote peace and to ensure it's not creating tensions. I think, you know, looking at the root causes of conflicts such as this is not the same as justifying anything that's being done. We are anti-war, we do not in any way support a military response to this type of thing.

But I think we do know that throughout history, you really have to look at the root causes if you hope to get to a sustainable peace. And I think that's what we're pushing for here. I think, you know, we have seen, as Marcus mentioned, and I think it's getting some attention now, but not enough, which is the fact that US weapons are just really ever closer to Russia's border and to Russia's capital. And that's something that, you know-- as much as, you know, the Mike McFauls wanna say it is a neutral act that is not threatening to Russia-- you know, every military strategist throughout human history knows the closer your weapons are to the other side, you have, you have an advantage and including in nuclear war. So I think, you know, there is, saying that that root cause plays a role here is not justifying anything, but it is recognizing that some of the issues we're gonna have to grapple with, if we hope to find a sustainable peace.

I also think that there's a confusion too, that you know, some on the left, you know, who wanna look at these root causes are in some way denying agency to the Ukrainians or in some way we are, you know, indifferent to the suffering of Ukrainians. And actually it's the exact opposite. You know, those of us who are promoting a diplomatic solution, we said at the outset that a lack of diplomacy with Russia was going to endanger the Ukrainian people. And that's exactly what happened. We had the US government saying, we know Putin's gonna attack. He's definitely gonna attack. They were saying they had the intel, but yet they refused to engage in any serious negotiations that involved, you know, grappling with Russia's concerns. And so now, and now we see on one side, I mean, we see hawks that are very happy to, you know-- they're very much benefiting from this carnage and it's helping their cause.

And so I think we need to be clear that it really is the left and the peace community that was most concerned about protecting Ukrainian lives and was, and is, and the only way to protect Ukrainian lives is not to plunge them into a 10-year long insurgency. Yes, that might bleed Russia, you know, and a lot of hawks want that, but it's gonna also harm the Ukrainian people horrifically, It's gonna destroy their country, and that's not in their interest. So I think that that's I think one place where we should really be clear is that it's the people who are supporting diplomacy that are most looking out for the Ukrainian people's interests. And I think another angle there that hasn't been mentioned is something that I've personally worked on for quite a while and is being widely recognized as a problem, although there's still a big effort to downplay, is the role of the far right in Ukraine.

And we are seeing MSNBC just publish a piece earlier this week that you know, saying that far-right fighters are flooding into Ukraine to get this battle training and that's really dangerous. It doesn't only threaten Ukrainian minorities in the future. It doesn't only-- it also endangers the potential for Zelensky to sign a peace deal because these far-right groups have called, have accused him of treason, have protested him and have threatened to overthrow him if he would sign a deal. But of course these are gonna be battle-trained, battle-hardened fighters that can return to other parts of the world as well when they're done. So, you know, I think that's been a-- it should be a major focus for the US, particularly US-based or any NATO-based peace community where we should ensure our weapons are not going to those forces and not helping to create a problem that is going to far outlast this conflict and is going to go far outside this region.

Helena Cobban (00:25:42):

Erik, thank you. Wow. we've had three great presentations from our guests, Richard. I don't know if you can pull it all together or just give your own, just give it your own take--

Richard Falk (00:25:56):

Well, first, let me say that these three presentations were very illuminating about the central issues that confront America in relation to Ukraine. And I think the point of consensus that's very valuable to underscore is that the condemnation of Russian aggression is not an excuse for not looking at the irresponsible behavior of NATO and the US in provoking the crisis. One cannot decontextualize what has been happening since February 24th, without looking at the buildup of geopolitical pressure that led Ukraine to also behave in a provocative way. Again, I endorse Bill Fletcher's point that this is a clear instance of violating international law, the UN charter. At the same time, I would recommend people to read Putin's February 21st speech to the Russian Security Council in which he goes through the efforts that were made by Russia to accommodate Europe, and even to turn a blind eye toward the earlier expansions of NATO.

He also in that speech relates his own effort to propose that Russia joined NATO. He made that proposal apparently to Bill Clinton. It doesn't justify the aggression, but it does explain the moral and legal and political hypocrisy of the United States, both in terms of what has induced and led to the outbreak of war but also an erasure of our own past, which in many features resembles what Putin is doing, Russia is doing, in Ukraine. And we have consistently intervened in behalf of regime change and denied sovereign rights of other states in situations that were non defensive. We have, have also turned a blind eye to anti-democratic autocratic regimes that were geopolitically aligned with us. So that the self-righteous aspects of the response to the situation in Ukraine is really very misleading and deceptive and paves the way for this new surge of excessive militarization and a withdrawal of resources from domestic priorities.

And that will be the effect of-- and so I would very much endorse what Marcus Stanley said about the importance, the urgency of what I would call geopolitical de-escalation. In other words, not only do we need to do our best to end the killing and the violence in Ukraine, but we also have a very strong set of interests that should justify trying to create a condition that is conducive to maintaining world peace and reducing these tensions that have been built up in recent years first against China, and now against Russia. Because that prevents not only the domestic agenda, but it also makes it much more difficult to respond constructively to the climate-change crisis and to a bunch of other global priorities. So there are many reasons I think, to explore how we go about achieving geopolitical de-escalation.

And a beginning of course, is this, the three points that Mark has mentioned with respect to Ukraine itself, the demilitarization, neutrality, and restoring the Minsk approach to Donbas in a way that really does recognize that Ukraine abused those past agreements and must be held accountable for preserving the, protecting the human rights of those people living in the Russian-majority provinces in Eastern Ukraine. So I would just end by saying that these two levels should not be confused, but that we should understand that stopping the aggression does not justify aggravating the geopolitical tensions.

Helena Cobban (00:33:18):

Thank you, Richard. That is a great point. Bill, I'd like to just come back to you, what do you see as the prospects for diplomacy? I mean, I definitely heard your plea that we all recognize the illegality of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. But realistically here we are, we have two nuclear powers at the brink in a way that they have not been since since December, 1973, you know, when Nixon and Kissinger announced Def-Con Three. And that was all over the Middle East, over the Arab-Israeli war at the time. And that got defused, as the Cuba missile crisis had earlier been diffused, through diplomacy. So what prospects do you see for actually defusing this crisis through diplomacy?

Bill Fletcher, Jr. (00:34:19):

Well, I wanna answer that by saying I think that we agree on this panel on certain things and then disagree pretty strongly on some other things. So I think that we agree on the historic criminality of US foreign policy. I think that we agree that NATO should have been disbanded when the Warsaw Pact was disbanded. I think that we agree that there were provocations by NATO. And then our agreements start to become a little bit less clear. For instance-- and I can see it in the chat-- there's a lot of, of interest and excitement (I use that term very loosely) about the existence of fascists in Ukraine and not one commentator that I've seen, at least in the chat has talked about the fascists in the Kremlin or the relationship of the Putin regime to global fascists.

And I find that fascinating. I also find it fascinating that no-one has mentioned the Budapest Accords of 1994. And I think that this is really important because had the Budapest Accords not been signed, we might be having a very different discussion right now, since until that time, Ukraine had the third largest nuclear arsenal on his planet, and they turned over those weapons to Russia on the, on the basis of the agreement that Ukraine would never be, be invaded. Now, did I say never? Yeah, I think I said never: would never be invaded. Now, it's interesting because when we talk about geopolitics, let's understand the lesson that Russia has taught the world, which is don't give up your damnednuclear weapons or weapons of mass structure, because the reality is you make a deal with one of these big boys and they may violate it when it's in their interest and boom, right?

And so I think from the standpoint of world peace, this is really, really dangerous, incredibly dangerous a lesson. I think that the issue then specifically about diplomacy Helena, is that this will need to be mediated. I don't think that we in the United States can give Crimea to Russia. Last time I checked, it was never part of the United States. Maybe I'm wrong on that. And I think that there needs to be a negotiated settlement that involves powers like China, but also, I would say South Africa, Mexico, Finland, Switzerland, some sort of multinational team that's assembled to carry out the mediation. I think that a settlement is probably, I would say definitely doable, but the security discussions are going to necessitate, not simply a discussion of security for Russia, but a discussion of security for the entire region.

And again, many progressives have talked about the threat to Russian security and about the growth of NATO. Let's be clear. The growth of NATO was not simply the machinations of George HW Bush and Bill Clinton, but the countries that had been in the former Soviet bloc, that were fearful of Russian invasion and aggression, and desperately sought to join NATO. So in other words, a security discussion is not about who gets close to Russia's borders. It's about how do we guarantee the security of the region. Final point: this is not June 22nd, 1941. We're not looking at a situation where there's prospects of great land invasions of Russia where in the case of Operation Barbarossa, it was what two or 3 million German troops and their allies. We're dealing with a situation of hypersonic missiles, ICBMs, et cetera. And so the issue of security has to be thought about very differently.

I know I said that was gonna be my final point, but it's not. My final point is that when Putin announced the invasion, what was fascinating was what he talked about and what he really downplayed. What I would've thought he would've talked about was NATO, NATO, and yet again, NATO. Instead, what he decided to do was to challenge the existence of Ukraine as a nation. And I would argue that gave away his hold card, that what was driving this invasion was less about a threat from NATO; but when he described Ukraine as national fiction that told the world everything. And I think that's what makes the discussions about negotiations very complicated, because if the objective is to guarantee security, I think that the path to that is pretty straightforward. If the objective, however, is to reconstitute Russia and its sphere of influence, then we're talking about a very different kind of negotiation and therein, I think, lies a great danger.

Helena Cobban (00:39:59):

So Bill or anybody else-- well, I'll maybe send it to the other two for now. You know, you've talked about the need for mediation in order to resolve this issue. And I completely agree with that. Why is our government not involved actively in such diplomatic efforts? And what can we do in the peace movement to shift the balance of pushing like, the balance of public opinion, to pushing for a negotiation rather than for all these militaristic outcomes? I don't know. Anyway, Erik, you wanted to say something?

Erik Sperling (00:40:43):

Yeah, I think I can touch on that, but also just a few of the points there. I think, you know, it's always a really interesting debate and, you know, these are arguments that have been fleshed out not as much as we could you know, in other spaces and spaces like this, which is great. But you know, I think part of the issue, you know, I guess getting just to the question of diplomacy and Putin's motivations, if the US thinks that Putin was acting in bad faith and that he was going to attack either way, which is essentially what they said, then it would've been in their interest to really show that they were open to concessions to say, look, we are willing to talk about all of this, let's get to the table, but instead they basically ruled out said that his demands were non-starters and that essentially guaranteed that he had very few options left.

And so I think part of the concern is, you know, if you think that he's in bad faith, then you should be so willing to be pushed for offer major concessions, see if he goes for it. And if he attacks anyway, you can show the world that he's acting in bad faith. The reality is, the world isn't united on this. We have mostly the Western, developed world that is leading this, and you have countries at the UN representing about 50% of the world population that wouldn't vote against Russia on this. So we do have a split, and the US having done that hard diplomatic work to really show openness to talks-- you know, would have, could have really helped build a consensus that maybe would've brought China over. Maybe would've brought India over. If you could show that Putin was not motivated as Bill said by that. But the US didn't.

And I think that gets to your question, which is, you know, why are they doing this? And I think there's a good part of the security establishment in the United States that was dying, is just thrilled to have Russia enmeshed in a conflict in Ukraine. These are not US bodies that are being sacrificed there. And they, you know, the US it's been revealed is providing massive intelligence support. I think this was the wild card that I think maybe Russia didn't fully understand was despite the fact that there are no troops, the US is providing, you know, some of the world's best intelligence information and strategic guidance to this war. And so I think Russia probably did not expect that. So I think, you know, I do think there is a big group of people who are thrilled, would love to have Russia go through that.

So I think, you know, to answer your question, I think we really need to look out there are going to be Ukrainian voices more and more that say, you know, we don't want our country to be subjected to a decade of an insurgency. That's not gonna be good for our people. And so where we see opportunities for Ukrainians calling for a diplomatic offramp, that's a great opportunity. But I think in general there's a range of different approaches. I mean, looking at the way this has affected the global economy that harms tens, if not hundreds, of millions of working people, both here and abroad, you know, we really need to be honest about the costs to working people of this war and both on Ukrainian people and working people more broadly. There's one issue I just wanted to respond on the far-right question.

You know, I think the reality is that there's no far right movement in the world today that has the level of battle-hardened, battle-trained far right fighters. Yes. We have people we call, you know, people on the left, let's say, our far-right here in the US, in Russia, they [in Ukraine] have, you know, not only do they have battle, they are trained in battle armed with the best weapons in history with the US weaponry. They are also, they also very much you know, enmeshed in the government, you know, we have a deputy commander of the Azov battalion who's--

Helena Cobban (00:44:27):

Erik. I think you said in Russia, I think you're talking about in Ukraine.

Erik Sperling (00:44:30):

Right? Oh, I'm so sorry. Yeah. In Ukraine, thank you. Yeah. In Ukraine, we have the Azov battalion, the deputy commander is the chief of police of the Kiev region. I mean, and you, you find these officials, a speaker of parliament for the most of the last five, six years was a renowned, you know, famous far-right leader there. So, you know, there is-- yes, of course we have far-right figures in the US and in Russia-- but what's really key is that we're not calling for supporting Russia militarily. And so we have a unique responsibility when we are pumping weapons into a conflict, just as we did in central AmErika, in the eighties to ensure that we are not creating groups that are going to commit horrific human rights violations.

And neo-Nazis by the very nature, far-right people by their very nature, they are guaranteed to eventually create, cause and commit horrific human rights violations. If we have armed them, we are complicit in that. We're not complicit in the Russian far-right. And we should never be complicit in it. And that's really important. So I think that's a little bit, I think that's a really key distinction. People say the same thing about us in Yemen. Well, do you support the Houthis? No, we don't for a second want to give one weapon to the Houthis and that's what we should apply to the other side as well.

Helena Cobban (00:45:50):

Marcus? Yeah.

Marcus Stanley (00:45:52):

Yes. So Erik said a lot there and there, there's some very interesting stuff in the chat and the questions I wanna get to. But I just wanna point out that the logic of the position that Bill laid out, which is essentially that Russia is the head of a global expansionist fascist movement, that Russia is not trustworthy in relation to the sovereignty of any of its border states. The logic of that is that there really isn't peace to be made here, that we have to drive the situation to a decisive Russian defeat and possibly regime change. And I think that, you know, I think that we need to realize the implications of that. And frankly, there, there are a lot of people in the US government and in the, in the network of more hawkish think tanks in DC, who I think share essentially this view, that Russia's actions are unrelated to to any of its national or geographic interests, but have to do with a fascist, expansionist authoritarianism that is inherently aggressive and simply must be stopped militarily.

And while I think we have to support the right of the Ukrainian people to self defense, I think that's a dramatic oversimplification of the situation. And it also commits us essentially to a new Cold War, a divided Europe, and frankly, a very dangerous sort of policy of backing Putin into a corner and potentially escalating this war, which will have massive costs for the Ukrainian people. And just one small thing I wanted to, to talk about and how I think it's an oversimplification. Bill pointed out an element to that very long speech by Putin, which is unfortunately no longer available here in English, justifying the war and said that he was questioning Ukraine as an independent nation, which to some degree on some parts of Ukraine, certainly Crimea, he did, but Russia was quite willing to live with Ukraine as an independent nation through the nineties.

And really up through 2014, they were trying to draw them into their orbit, but not in anything like this kind of militarized way. And things changed very dramatically in 2014. I think partly because of what Russia felt was the evidence of the involvement of the US pretty directly in the 2014 Maidan uprising against the Ukrainian government and a new step in turning Ukraine into sort of an agent of the United States that was hostile on Russia's border. And, and that was another very big emphasis in Putin's speech. So I, I think we need to think about how to dial back, and we need to think about what the possibilities for the diplomacy are here. And of course, as a final little thing, Bill's quite right, that NATO expanded in part because of the desires of Eastern European countries who'd been victim by Russia over the years, in a way they haven't been victimized by the US, but I think the us needs to look more broadly than these, these nationalist conflicts in Eastern Europe. And we need to take a overarching view of of world peace and a sustainable peaceful European order.

Bill Fletcher, Jr. (00:49:31):

Helena, I have to just disagree with Marcus. I mean, come on now. So the question is what did Putin actually say in that speech? He went through a diatribe against Lenin and Stalin on questions of national self-determination, Marcus, he didn't talk about just the Eastern region of Ukraine. He was talking about the existence of Ukraine, and there's a long history to what was once called Great-Russian chauvinism. Right? And so I think we've gotta be-- what I'm saying is that if you don't understand what's going through the guy's head and his regime, then any negotiations will fail because we will be missing the point. I've been at enough contract negotiations to know that if you don't have a sense as to what the other side is thinking about, you're gonna fail big time. So I think it's really important that we understand what these motivations are.

The second thing is acting as if the fascists can only be found in Ukraine and that in Russia, maybe there's a few problems, you know, a few people poisoned here, others there, why don't we interview the Chechnyans, right? Why don't we interview the Chechnyans and ask them a little bit about Russian democracy and, and Russian respect for tolerance and national rights. Why don't we ask them a little bit about this? I think we have to be understand that. Yes. I think one thing you and I would agree on is we've have to look at the broader context. I would also agree, however, that that the United States was irresponsible post-Cold War. And I've said that earlier, because my position is that NATO should have been dissolved immediately at the end of the Cold War. There was no reason for it to continue to exist, even when Gorbachev suggested that the Soviet Union could come into NATO-- even then they should have dissolved it. And even when they set up that association and I can never remember the name of it, professor Falk may remember, it's something-- it was almost like a Friends of NATO group that Ukraine and Russia were part of-- even then, which Russia pulled out of in 2014. I would say that... NATO should have been dissolved. But if we don't understand what's motivating some of these forces, then I think that it's-- We go down a wrong path.

Helena Cobban (00:52:07):

So Erik--

Erik Sperling (00:52:12):

Yeah, I just wanted to reiterate kind of what I was explaining, which is, yeah, we, I think we all agree there are far-right forces, but we have a unique responsibility at least as Americans. I think people in the UK and other NATO countries have a responsibility as well, if their weapons are... are being used and could be used in the future to harm minorities or to scuttle peace talks. So you know, I just want to be really clear, you know, we're-- I'm totally, you know, I would love to have influence, in my dream world, right, you know, if I could influence policy all over the world right now... We absolutely have our hands full trying to influence US policy, and it's an incredibly huge battle; probably be my life's work to do it. But someday I dream of maybe being so incredibly influential that I can influence other cultures, other societies that I'm not from.

But for now, our focus is on what the US is doing, which is arming and training groups that, there's already a lot of evidence these groups have done harmful things. There's already evidence these groups are enemies of peace. And the reality is, the groups that we're arming and training in Ukraine, or that are getting our weapons because we're not screening for them, they're actually providing assistance to Putin because that is his narrative. And when we downplay that, when we say, when we do whataboutism and say, well, Putin has Nazis too. That just makes it look, that just endangers the Ukrainians by making it look like we are happy to align with Nazis. But what Ukraine would be, in Ukraine's best interest, and what's in our best interest, and what's also morally right, is to take basic actions to screen out those folks from receiving US weapons and training. That would give us so much to-- do so much to be able to undermine Putin's narrative. But when we do this kind of, whataboutism, "Well, there's Nazis everywhere, so therefore we're okay working with them here." Or, "it's not a priority for us to ensure our weapons, aren't getting to Nazis--" That's just such a gift to Russian propaganda. I think that's what we really wanna undermine. And we really wanna to, to make sure that we're not doing that.

Helena Cobban (00:54:11):

So if I can just give a program note here, we're coming up to the 60-minute mark and the discussion is really rich and really productive. And we have a number of questions in the Q and A box. So I hope that our three guests and that my co-host Richard can join me in staying on for another 15, 20 minutes, which would be great. If any of you has to leave. Well, please don't! It looks like Erik already left, but I, I think maybe he just needs to, I don't know, deal with a cat or something, who knows? So I'm gonna throw in the first question here from the Q and A box. Oh, hi. Welcome back, Erik. So here's a question from our board member, Rick Sterling, who asks, why do you think 40 countries representing about half the world's population, including China, India, and South Africa did not agree with the condemnation of Russia. Some of them such as Cuba said, Russia has the right to defend itself. So I guess, Marcus, you haven't spoken much recently. But anybody?

Marcus Stanley (00:55:22):

People are-- people are actually, you know, what are-- Can one of the other two go first, because I was gonna look up something that the Chinese said on specifically this issue.

Helena Cobban (00:55:36):

Okay. Anybody about why 40 countries in the world did not agree to to, to censor Russia at the General Assembly and what does this mean for-- And these are nearly overwhelmingly countries of the Global South. So what does this mean for our responsibilities as peace and justice activists, given that they have burning concerns specifically connected to the continuation of the war which is pushing wheat prices, oil prices, sky high for countries and communities that cannot afford that?

Bill Fletcher, Jr. (00:56:16):

If memory serves me, there were two votes. And the large number of votes in the Global South were not votes against the condemnation of Russia's aggression, but countries were not prepared to go along with sanctions against Russia. And I believe that part of the motivation is quite understandable, which is Western hypocrisy, that the the west particularly in the United States has been prepared to support-- I was gonna say tolerate, but support-- Israeli aggression against the Palestinians and Moroccan aggression against Western Sahara and other such atrocities, and yet speaks up when this happens. And I think that large portions of the Global South said, we're gonna have to have one standard when it comes to international affairs. So most of the world has been in favor of protecting national sovereignty and and respect for international law, but feels that when the west starts talking about taking steps, it's often very select in its choice. And I think that that position is quite understandable.

Marcus Stanley (00:57:45):

Yeah. I completely agree with with Bill on that, that from the perspective of the Global South, I mean we have-- I see this all the time in DC where there's recommendations out of Congress to you know, send State Department people to Africa and warn against colonialism by China or Russia. You know, it's really rich when the west warns Africa against colonialism by other parties or, you know, to talk about how these other states are threat to peace and democracy and the United States is not. So the hypocrisy is overwhelming. And I think the costs of these sanctions to the global economy as Helena mentioned are also very significant. And, and I think also, you know, China said in, in response to some of this criticism saying the US claim to defend peace by working on NATO expansion: is peace achieved? It claimed to prevent war in Europe: is war averted? It claimed to wish to peacefully settle the crisis: has the crisis been settled?

Marcus Stanley (00:58:57):

So just kind of this impatience that the west-- I think something Erik said earlier that if we made, if we were more public, perhaps these offers have been made behind the scenes, but if we were more public and more aggressive in pushing a settlement to this conflict on terms that, you know, were transparently fair to the whole world when the whole world looked at them, we would do better with our ability to reach out worldwide and actually put Putin in a more difficult position.

Helena Cobban (00:59:34):

So we have a couple of questions here. One from Ghassan Abdallah, who I believe is in Palestine, and one from Elizabeth Axttell, asking how we would describe the role of the US media in dealing with the Ukraine situation. And what do you think of the Western governments closing down media outlets that give a different discourse from the overwhelming Western corporate and pro NATO discourse? I mean, is this something that we need to deal with?

Bill Fletcher, Jr. (01:00:12): Yeah. It's-- I'm sorry, go ahead.

Erik Sperling (01:00:14):

Yeah, no, I'll just briefly, it's been stunning to me. I mean, for example, the way that I generally tend to try to ascertain the truth in a situation, and I guess, you know, I think some of other folks may have legal background, but I think anyone does this, is you wanna read both sides, right? That's that you read both sides, you read your opponent's argument, and I think it's been really amazing to me, you know, in this whole debate, how often I've asked people, you know, have you read, you know, what the other side is saying on this? Like, how do you respond to their point X, Y, or Z, people say, well, I haven't read that. You know, I'm not familiar with that. So I think that's been really troubling to me that there's no desire, not even just kind of at an academic level to really understand the opponent's argument.

And I think that of course has much worse implications than that, which is that people don't, you know, they don't grapple with their opponent's arguments. They don't read their opponent's words. And I think this is a really troubling trend that I do think we have to stand up against the right of people [not] to know what the other side is thinking. And yeah, it's been a very scary moment. We've seen including many people that, you know, some of-- in the media space-- that some of us may have come across or have appreciated their work; and they're being shut down. Because they're on a private, technically a private company like YouTube people are defending their sole right to do that. So I think it is a really troubling time. And I think we really need to stand up to say that, you know, it's critical to understand your opponent's argument, if you believe that you, you know, to be able to formulate and strengthen your own argument.

Helena Cobban (01:01:47):

Yeah. Bill--

Bill Fletcher, Jr. (01:01:48):

Just, yeah, I would say Helena, that, that there's two things. One is that the restraining of the press in the west and in Russia makes an actual settlement much more difficult. So for example, in Russia, jailing people for using the term war is not particularly helpful when what's going on in Ukraine is a war. But I think that when I look at the media in the west, what strikes me always is the lack of historical context. And if there's anything that I fault the Western media for, at least the US media, I'll say, it's that it's not simply that it provides slanted information but that it provides information often out of any kind of context. So people look at what's happening and for instance, they don't get the benefit of the kind of discussion that we're having today about the history, the history of NATO, for instance, or what happened at the end of the Cold War, or what was this whole thing that Putin was talking about when he was going after Lenin and Stalin? Why is that relevant to understanding what's going on? It's these things that we're often deprived of, and that's actually what I focus a lot of my attention on when I indict the media in the US.

Marcus Stanley (01:03:22):

I think everybody in the peace movement, in the peace/justice movement, has a big stake in this, because this, what we're seeing happening is sort of this creeping thing, where if you repeat sort of a talking point or an argument that is used by the other side in the war and we've seen people like a distinguished academic like John Mearsheiimer, who was quoted by the Russians in support of their own talking points. And he's, he's immediately "a traitor" and so on. That if you do anything like that, you're a foreign agent or a traitor. And we need to think about how that is going to-- You know, that is very, very dangerous for anybody in the peace movement who wants to add context in any setting, not just this war, but future wars. So that that's a terrible precedent to set. We really have to push back against that.

Helena Cobban (01:04:21):

Yeah. Richard, do you see anything about this sort of incipient McCarthyism that we have happening in the US media?

Richard Falk (01:04:31):

Yes. I mean, I support what others have been saying. And I think this Russophobia that has been generated by the Ukraine crisis is in some ways worse than anything that was characteristic of the McCarthy era, because it's directed so much at the Russian people, as well as-- and Russian culture, the banning of Tchaikovsky and wanting to send Russian students home-- and it really destroys the distinction between the crimes of the Russian state and the innocence of the Russian people, or at least the non-complicity of the Russian people. And we would expect a democracy to respect that distinction as one of the basic ways in which a constructive world order is sustained. And again, I would stress that so much depends on a willingness to engage in the tactics and strategy of geopolitical de-escalation, at this point. We don't want another Cold War. We can't afford another Cold War and it is more dangerous and more destructive than the initial Cold War.

Helena Cobban (01:06:18):

So I think I'll just ask all of our guests, what do you think would be the most productive talking points and strategies for us to follow, to resist the rush to escalation and militarization in the current situation? I mean, people in the peace movement all around the country really want to know what is gonna work and maybe we can learn from different people, you know, what has been working with their local representatives, but for all of you three, who like me we are all in here in Washington DC. We'd love to hear, I'd love to hear your views on what can really help stop the rush toward militarization.

Erik Sperling (01:07:11):

I would just say quickly, I think from our perspective, we're focused on looking for any opportunities for openings. So, you know, we're following the, the conflict following the Ukrainian side, and really anyone who's speaks up for peace, particularly in the Ukrainian side, but especially in the US you know, also yeah, but also in the US as well. Really getting behind those calls. You know, unfortunately it's painful, you know, I don't think anyone likes making concessions in talks to someone that you see as engaged in terrible behavior, but it can be for the better good to make those concessions; you can save lives, in this case, particularly Ukrainian lives. So, you know, lining up saying, you know, it's never fun to make those concessions in talks, but that is a critical part of talks. There are always painful concessions and we need to do that to avoid a 10-year insurgency that destroys Ukraine even further. That's the key focus. I think, you know, shining a spotlight on what US and Western weapons are doing definitely can be helpful, as much as people want to minimize and say, well, there are neo-Nazis anywhere, making sure that our weapons are not going to these groups I think is important. And then, you know, just really shining a light on the broader risk from nuclear war to global economic catastrophe, that conflict is creating and making the case that a diplomatic solution as painful as it can be is a tiny fraction as painful as what we're dealing with now and what we could deal with if it escalates.

Bill Fletcher, Jr. (01:08:37):

So let me join with Erik. I think an immediate cease-fire; mediated peace talks; a focus on regional security; and de-nuclearization. I think that this last point is something that I think that progressive forces around the world, and certainly here in the United States, have to really look at. That the constant possibility of nuclear exchanges, which is partly why I think it was so irresponsible for Putin to be floating those ideas, the possibility that something is going to trigger this is a grave danger. And I think that the progressive forces have to, re-raise the issue of denuclearization as part of part of our task going forward.

Helena Cobban (01:09:32):

That's a great contribution. Thanks. Yeah, Marcus?

Marcus Stanley (01:09:35):

And just supporting both Erik and Bill, I think, you know, we're in a tough situation because obviously Putin is brutal and he's the aggressor. And I don't think within the next couple of weeks, we're going to necessarily see-- I mean, I hope I'm wrong, but I think he's going to press this war over, over the next couple of weeks. But I think over the longer term, we need to stand up for a diplomatic solution and creating space for a diplomatic solution because-- and some kind of negotiated rearrangement of the security order in that part of the world, because we have a lot of people, people have been saying in DC that we need to look forward to a 10 to 15 year war, an insurgency, to Ukraine becoming like Afghanistan, which would be a disaster for the Ukrainian people. And that's the alternative, you know, a 10- to 15- year war and restarting the Cold War.

So we have to to stand up for those diplomatic possibilities. And, and I think there are possibilities that can preserve meaningful sovereignty for Ukraine here. And that is a tough thing. Diplomacy always involves compromise, but that, that will also still be a check on Putin, and I think the de-nuclearization, the way that, that we have both we and Russia have been starting this sort of short-range missile arms race in Europe, that is incredibly destabilizing and has to stop. And I think that needs to be a target for for diplomacy and for agreement as well, because as long as that's going on, you know, it's gonna be very difficult to have a sustainable peace.

Helena Cobban (01:11:31):

Those are great points. Now, I think we should probably wrap up. So Richard I'd love to hear some final wisdom from you and then we'll thank our guests.

Richard Falk (01:11:42):

Well, I think we've heard a great deal of wisdom from our guests and I would just underscore what Bill just said about denuclearization and keeping regional security in mind in moving toward a better diplomatic place. And I think all of those points that have been emphasized by all of us, and I think there isn't much difference between our perspectives except on this issue of whether the Putin support of the rightwing autocracies around the world and in the US in particular is symmetrical with, or asymmetrical to, the role of neo-Nazis and fascists in the Ukrainian context. I think that's the only point that there really is some difference of opinion about.

Helena Cobban (01:12:58):

Thank you. Yeah. I guess my perspective on that is that, you know, obviously arming neo-Nazi, empowering neo-Nazis, wherever it happens, is to be decried. Absolutely. But I, as a tax-paying US citizen, have a special responsibility for what my tax dollars do. And I've wrestled with this issue over the years. Just regarding regional orders, the one body, well, one of the bodies that has not been mentioned here thus far is the Organization for Security and Corporation in Europe, OSCE, which I think should be a vital force in a mediation effort and a part of a kind of verification and monitoring effort after a peace agreement. But we still have a, a long way to go before we can shift this massive, great ocean liner of US policy around from its current direction, going toward militarization and polarization and demonization of, of Russia-- to shift this great ship of the American state back or well to where it should be in terms of a force for, for peace, de escalation, negotiations.

So let's hope that all of us together can do this. I want to really thank all of our guests, Erik Sperling from Just Foreign Policy, Bill Fletcher from the Institute for Policy Studies, and Marcus Stanley from the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft. And of course, to thank my amazing co-host Richard Falk, who's-- I think this whole series was your idea originally, Richard and it's been a wonderful experience to be working with you on this. We do have details of the whole upcoming schedule of our webinar series at our website, www.Justworldeducational.org. I want to remind you that if you go to our website, you'll find a donate button and you can donate hopefully as generously as possible.

Speakers for the Session

Helena Cobban

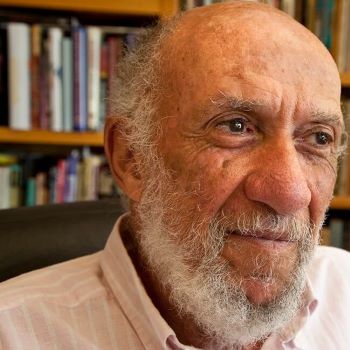

Prof. Richard Falk

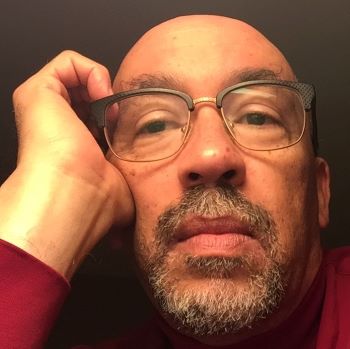

Bill Fletcher, Jr.

Erik Sperling

Marcus Stanley

Support Just World Educational

JWE has a golden opportunity to make a difference in this country...

Stay in touch! Sign up for our newsletter: