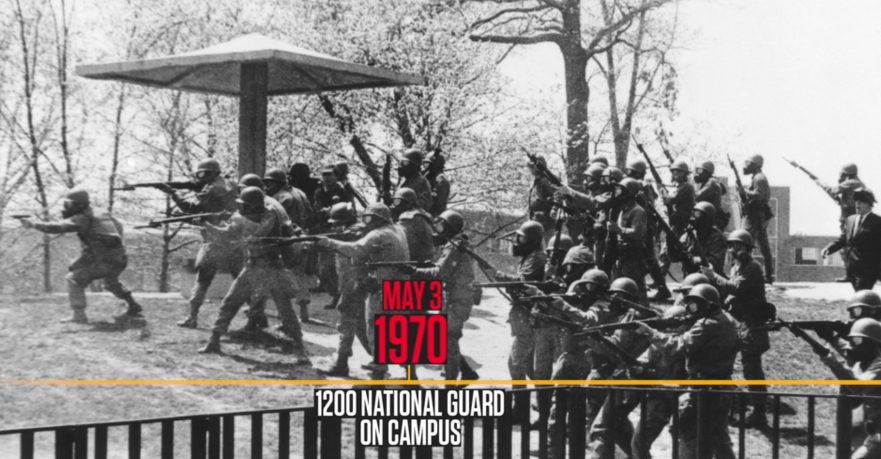

On May 4, 1970, the campus of Kent State University in Kent, Ohio was the site of one of the key moments in the broad movement in the United States that protested the US-Vietnam war. Amid a series of large demonstrations that roiled the campus for several days, heavily armed members of the Ohio National Guard were deployed. (The photo above, of the Guard presence on the campus on May 3, 1970, is a still from this short video about the events of those days.)

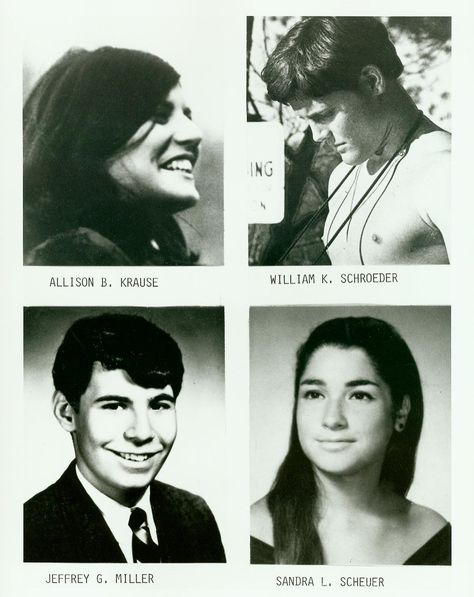

On the afternoon of May 4, one group of Guardsmen opened fire on the protesters, killing four of them.

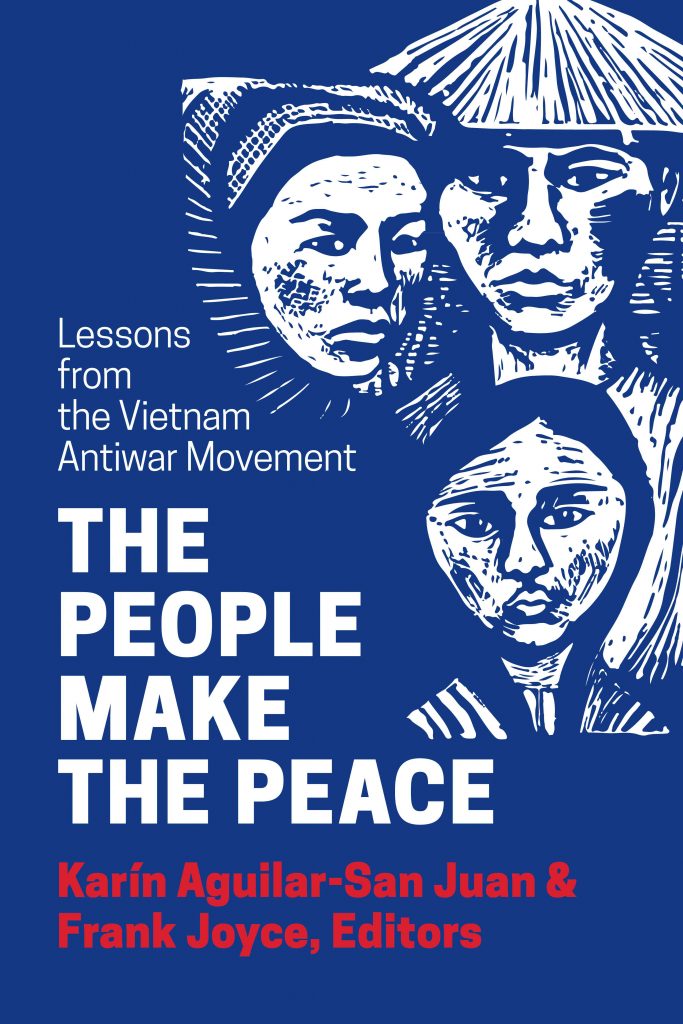

With the 50th anniversary of that incident now just a few months away, we are pleased to publish the following reflections by Karin Aguilar-San Juan, a professor of social movements at Macalester College in Minnesota and co-editor of The People Make the Peace: Lessons from the Vietnam Antiwar Movement, on a recent visit she made to the Kent State campus.

by Karin Aguilar-San Juan

On October 25, 2019, I was fortunate to join a panel titled “Vietnam War Opposition in History and Memory” hosted by Professor Jerry Lembcke at the Peace History Society conference. My comments focused on the People’s Peace Treaty of 1971—an effort led by students in South Vietnam, North Vietnam, and the United States to end the war by crafting a simply worded peace document that would eventually be embraced by prominent cultural and religious leaders and, eventually, the U.S. Congress.

As students, Doug Hostetter, Becca Wilson, and Jay Craven traveled to South and North Vietnam during the war itself to “broker” the People’s Peace Treaty. They tell their riveting story in our book, The People Make the Peace.

This year’s Peace History Society meeting was especially moving as it was cosponsored by the School of Peace and Conflict Studies at Kent State University in Kent, Ohio. Fifty years ago, four Kent State students were shot to death on campus by the Ohio National Guard. The May 4, 1970 killings marked a flashpoint in the international history of the opposition to U.S. war, specifically Nixon’s invasion of Cambodia, launched just days earlier.

Shortly before I arrived at Kent State last month, Doug Hostetter sent me a copy of a letter written in 1971 by Nguyen Thi Binh aka “Madame Binh.” At that time, Mme Binh was the international face of the Provisional Revolutionary Government (PRG) of North Vietnam, and after the victory of North Vietnam, she served as the Vice President of Socialist Vietnam. In the letter—typewritten on yellowing paper—she thanks the U.S. students for their activism to end the war. She specifically references “the Kent Four,” giving direct proof that this tragic event had—and still has—international proportions.

I gave a copy of this letter to Ethan Lower and Olivia Salter, two Kent State undergraduate students and political science majors who are serving on the May 4 Task Force, a student-led committee that is helping with the upcoming 50th anniversary commemoration. It’s rare for today’s students to be so committed to understanding the Vietnam War, and Ethan and Olivia were impressed to learn about Mme Binh’s feelings for the history of their campus.

….

And here is an article Prof. Aguilar-San Juan published about her recent visit to Kent State, in Macalester’s publication, the Mac Weekly:

The Last Call: Kent State then and now: anti-war movement lessons

by Karin Aguilar-San Juan

Many years ago in a small Midwestern town, Kent State University students gathered in their campus’ Commons to make their voices heard. Unable to cast ballots until they were 21, the students were just the right age to be drafted and sent to Vietnam. The war’s senseless violence and hopeless direction drove them to question authority and to join collective movements — but that wasn’t the only impetus for their actions.

Many student activists also targeted anti-black racism, patriarchy and sexism — and what they saw as overly restrictive prohibitions around alcohol and drugs. They organized for ethnic studies and other programs to support black students. They spoke out against 1950s-era dormitory codes regulating the behavior of female students.

One day, King Richard — President Richard Nixon — declared that instead of withdrawing U.S. troops from the war in a program he promised would lead to its “Vietnamization,” he decided instead to continue the fight in Vietnam and expand deeper into Southeast Asia, with an invasion of Cambodia. At Kent State University — a public, working-class institution at the center of Kent, Ohio — hundreds took to the streets.

For days and nights, anger raged in the town of Kent. Eventually, an ROTC building was burned to the ground—and anti-war activists were assumed responsible. Pledging to “eradicate” the campus protesters, Ohio’s Governor James Rhodes ordered 1,000 members of the Ohio National Guard to occupy the Kent State campus, fully armed with bullets, teargas and bayonets. Rhodes demanded that all campus rallies be dispersed.

Nevertheless, up to 3,000 remained on the Commons — students, professors, curious bystanders and hundreds of active protesters angered by the suddenly militarized situation. Most people, including university president Robert White, were unaware that the troops had been issued live ammunition.

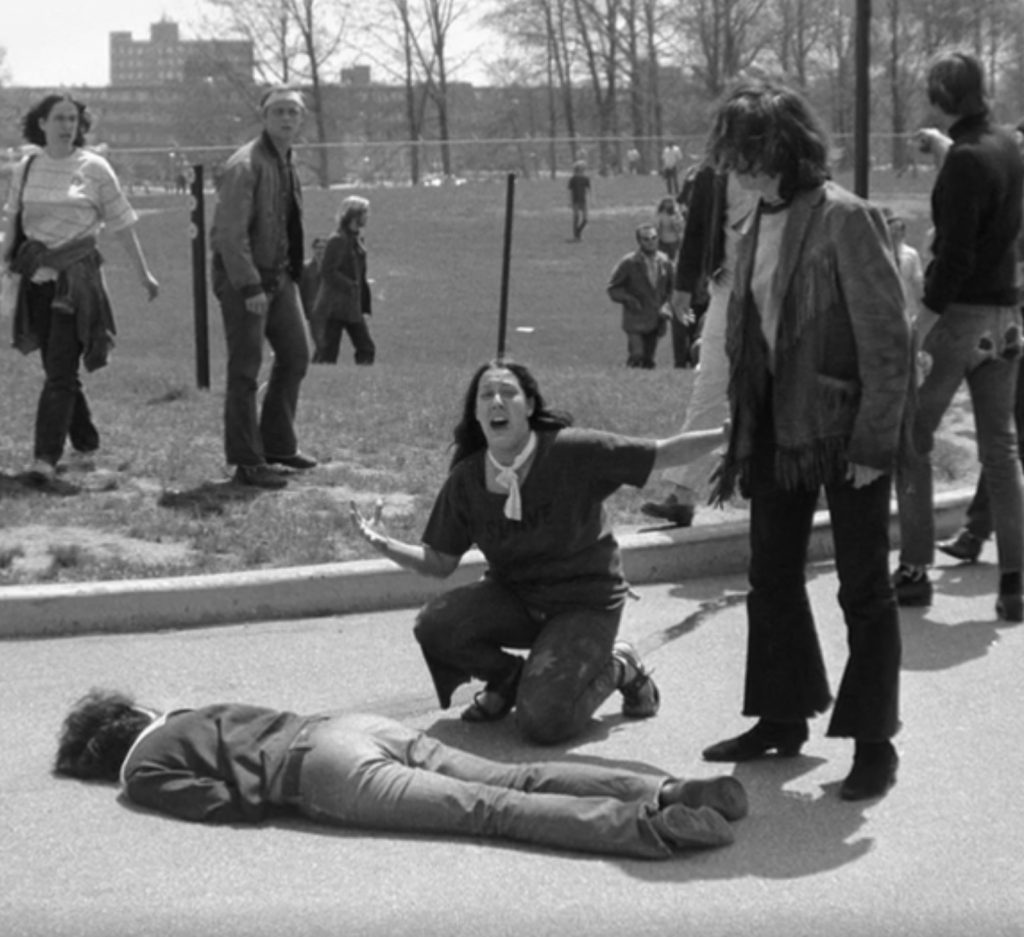

Students gathered on the Commons for an initially peaceful demonstration opposing the presence of the Guardsmen. Shortly thereafter, the Guard ordered the protesters to disperse. But they didn’t, and instead threw rocks at the Guardsmen, who responded with live ammunition.

In the space of a moment, the Guard shot four students dead and wounded nine, paralyzing one. For the heartbroken mother of one of the Kent Four, “the myth of a benign America where dissent is broadly tolerated was one [more] casualty of the shootings.”

Five decades later, this true and terrifying nightmare deserves our attention because of its eerie resemblance to state-ordered violence in response to political dissent on campuses today.

There is, of course, much more to the story of Kent State — including the impact of class and race. Historian Christian Appy refers to Vietnam as a “working-class war,” since four out of five soldiers came from blue-collar families, and a majority of those were black or brown. By 1970, many Kent students were combat veterans, and some of those vets joined the anti-war movement to add an extra edge to debates about war.

Meanwhile, the Guardsmen who occupied campus were either veterans or enlistees who served as an alternative to deployment in Vietnam. Why did they fire their guns on people who clearly had no place to run or hide? The National Guard insists that they fired in “self-defense” and the ensuing federal criminal and civil trials unfortunately accepted this position. Some critical studies of the Kent State Massacre hold the Guard responsible, and say their decision to fire into the crowd was unjustified.To settle the case, the state of Ohio paid $675,000 to the wounded students and to the families of the students who were killed. But the statement issued and signed by the National Guard stops short of admitting wrongdoing, merely expressing regret: “In hindsight, the tragedy of May 4, 1970 should not have occurred.”

Immediately after the shootings, administrators around the country closed nearly 500 university campuses. When classes at Kent State resumed in September, 2,000 students spontaneously organized in a candlelight vigil for their dead classmates. In the months and years following, Kent State created a syllabus for a May 4 course required for all incoming students and installed a large, granite memorial and smaller memorials on the site where each student was shot. They also added a Visitor’s Center with an exhibit and instructional materials.

The May 4 shootings at Kent State poured fuel on the fire of the anti-war movement. All over the Midwest — from Madison to Milwaukee, Ann Arbor to the Twin Cities — marches and teach-ins proliferated. Surely influenced by the Kent State shootings and the blatant contradiction between the age for draft eligibility and the age for voting, the U.S. Congress ratified the 26th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution on July 1, 1971, lowering the voting age to 18.

While it took several more years for the U.S. military to withdraw completely from Southeast Asia—in large part due to the pure moxie of the Vietnamese people—the power of students and ordinary people to bring war to an end should never be dismissed.

Sadly, wars continue. And so do paradoxes at Kent State. Guns are currently banned for all Kent State students and employees, although Ohio is an open-carry state. At her 2018 graduation ceremony at Kent State, Kaitlin “Gun Girl” Bennet slung a semi-automatic AR-10 over her shoulder, wrote “Come and Get It” on her cap, and instantly turned herself into a mascot of the gun lobby of the town and nation, gaining a vast online following in the process. The otherwise mostly male and white pro-gun advocates at Kent State argue that guns should be allowed on campus as a “safety measure.”

The idea of guns making any campus safe is mind-boggling, even more so at Kent State. None of the student protesters were armed on May 4, and for the most part they were peaceful. The National Guard should not have dispersed them, they should not have thrown teargas grenades, and they definitely should not have shot or killed anyone.

Those were dangerous times, much more complicated and volatile than the legend of sex, drugs and rock’n’roll that defines conventional understandings of the Vietnam era. We should put more effort into inquiring, learning and reflecting on the past in order to learn from it.

*I dedicate this piece to Olivia Salter and Ethan Lower, undergraduate leaders of the May 4 Task Force — the student committee who will help to shape the 50th commemoration of May 4 on the Kent State campus.