Transcript: World After Covid with

Medea Benjamin and Helena Cobban

Webinar recorded on June 17, 2020

Video and Session Transcript

Helena Cobban, JWE President (00:02):

Hi everybody. I'm Helena Cobban. I'm the president of Just World Educational. And I'm delighted to welcome you to the second session of our ongoing conversation with a broad variety of panelists in our world after COVID series. Today we're going to welcome Medea Benjamin. Medea, It's great to have you with us.

Medea Benjamin (00:25):

Well, hello, Helena, and nice to be on with you. It's a little difficult to imagine the world post-coronavirus, but I'm happy to make an attempt with you.

Helena Cobban (00:35):

That's great. Well, you know, some people actually wrote to me and said, you know, I'm sitting here, I'm crouched in my apartment building, and I don't feel that we're after COVID yet. And I completely appreciate that we are not after COVID, but we are after the outbreak of COVID and after the world has seen how's how terribly badly United States has performed. So that's kind of the context for this ongoing discussion.

Last week, we had Richard Falk with us and if you didn't catch that session, you can actually catch it. Now I'm about to share the screen with you. I have completely the wrong screen up here, but that's all right. I know you all can bear with me. Okay, so that is https://bit.ly/WAC-Falk. And you can go and watch the session with Richard Falk there.

And this week, as I previously mentioned, of course, we're extremely happy to have Medea with us. We're going to be discussing some really exciting topics. Medea and I actually ran through a few of the ideas and they were just bubbling out of the conversation.

Sorry, this screen share thing is always my bugaboo, but there we go. So now you'll know some things about Medea Benjamin. You may not know that she's actually written a lot of really wonderful and important books and is currently doing a lot of work on Cuba, work on ending sanctions and so on and so forth today.

We're going to be discussing Venezuela, Latin America, Cuba, Iran, the Pentagon budget, the need to not have a war with China - hot or cold - and various other great things. So, Medea, let's leap right in.

I would like to ask you what you think are the possibilities of getting rid of this idea of U.S. leadership of the world as well.

Medea Benjamin (03:10)

Well, for many people around the world, that has already happened. For many of them before coronavirus and before these latest uprisings in the U.S. around police brutality, but these two things have brought it to the floor.

We have shown the world that we have a failed system here, a system that's not able to care for the health of its people, whose atomized privatized healthcare - I didn't use the word system, because it's not a system –

Helena Cobban (03:50):

It doesn't have much to do with either health or care.

Medea Benjamin (03:52):

It has to do with profits. And it has to do with us as a people not being strong enough to have demanded a universal healthcare system and gotten it. So there on the health front, we have showed the world that we do not have any kind of model to be copied by any means.

And then on top or in the midst of this comes these waves of police brutality on camera. Because we know this is an ongoing issue and it's now because it's caught on camera. And a lot of people have had a chance to see this and having this wave of uprisings now in the midst of a pandemic is something quite extraordinary.

I was thinking back Helena, just in, I think it was in November of last year, I coauthored a piece on why people in the U S haven't risen up. And we were looking at all the uprisings that were going on around the world from Latin America, like Chile, Lebanon, Iraq even in Europe, you saw the Gilets-Jaunes (Yellow Vests) in France. And we were saying, you know, what's wrong with the American people. And we kind of made a list of all the different reasons that American people haven't risen up and all that has suddenly changed because now American people are rising up.

And it's an interesting - one of the reasons we put the American people don't rise up is because a lot of people who are activists put their energy into elections. And that was true in this cycle of all the energy that went into Bernie Sanders’ election, which was a very important historic campaign that opened up a lot of possibilities and discussions. But when it was tamped down by the Democratic establishment, and instead they gave us Joe Biden, the activists have now put their energies into different things.

And that is one reason why we see a bubbling up of new activism and so much support for the Black Lives movement that has been extremely active in the last couple of years. So the possibilities now of the world looking towards the U S and saying, wow, we have to show solidarity for the U.S. uprising - because at one point it was pity.

Remember there was a great op-ed that came out saying, I never thought we'd have to pity the United States. But look at all the people who are dying from coronavirus and the lack of leadership, and now it's turned into solidarity. And I think this is a momentous occasion when you have all over the world, people rising up in solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement in the United States, and much larger than that, in solidarity with people in the U.S. We're rising up against a failed system and against a U.S.-dominated globe. So I think the possibilities are tremendously right now for the rest of the world to be looking elsewhere towards U.S. leadership, if indeed, they were still looking towards the U.S.

Helena Cobban (07:23):

Yeah, I've been, actually, I've been trying to write this article for a couple of weeks now called “America and the world.” Let's junk the idea of asserting a right to leadership and move from leadership to membership, because, you know, we are members of the world community, and, and that's, I think a much better model. By the way, people who are on this, the many attendees that I see who are on this, if you want to ask questions, that will be time to do that at the end. Medea and I are going to have our conversation for roughly half an hour. And then at the end, there will be questions, answers, comments, discussion and you can do that via chat or via the Q and A function. If you want to get your question registered early, probably the Q and A function is a good one.

Meantime, back into our bilateral conversation Medea. So if we're going from like U.S. leadership to U.S. membership, that obviously involves a lot of things like returning to become members in good order of the World Health Organization or the UN Human Rights Council, or indeed the United Nations itself, which has been like treated like junk by this administration and previous administrations. You been talking quite a lot about trying to restore a good neighbor policy with Latin America which I think is fascinating. So talk more about that.

Medea Benjamin (09:07):

And certainly it could be the same principles for around the world. Instead of having a country that thinks it has the right to dominate the rest of the world and to decide who is in power and, you know, Helena, it's so ironic hearing Americans say, “Oh, that Russian intervention in our elections” and those kinds of things. You know, it's been the modus vivendi of the United States to be constantly interfering and dictating who will run other countries.

And the Trump administration continues in that tradition. You look at the tremendous pressure that this administration is putting on countries like Venezuela, Iran, North Korea, Cuba, the economic sanctions that are so devastating to countries around the world and how this is part of a regime change strategy. And then you also see the continuing wars that Trump had promised to get us out of and didn't, and then you see the continuation of the over 800 U S bases around the world, the empire in all its different forms.

And we recognize that if we're going to transition from an empire to a country that is one of the many countries in the global community, how would that happen? And a good neighbor policy we've been looking at, particularly for Latin America, because it hearkens back to Franklin Delano Roosevelt in the 1930s, that wanted to make a radical shift from the U.S. interventions, which had been constant military interventions in Latin America, U.S. dictating governments in Latin America - to one that was more a neighbor working together cooperatively with other countries, but refusing to use military intervention.

There were problems with that and that there were still lots of economic pressures that the U S did on other countries. But it gives us a framework to say, what would a good neighbor policy be like today? And of course it would be noninterference in other countries’ internal affairs, it would be getting rid of the U.S. military bases that are there. It would be economic policies that are not in favor of U.S. corporations, but would be more of a fair trade. And now in this moment where at, when there's a lot of questioning about the hyper globalization that we have as an economic system, that the U.S. in large part was pushing for decades now I think it is a moment when there's going to be a rethinking about how we supply our food, how we take care of this chain of supplies that has shown to be so fragile than it is - well for Latin America, we have gotten the Latin American nations on this terrible food system, that depends on imports and exports instead of local production.

So I think a good neighbor policy would be supporting a local food production, more sustainability locally. And then there comes the issue about the immigration policies and one that was much more favorable to people who were fleeing from hostile governments. And the U.S. to stop supporting abusive governments, whether it's the right wing government in Brazil right now, or the government that really is a narco-government in Honduras right now, pulling U.S. support for those kinds of governments.

These are the kinds of things that would have to be rethought in terms of how would we act not only in Latin America, but act in the world. And it would be an extremely radical change for the United States right now. But I think in the long run would be good for us here at home. Certainly, it would help us stop spending massive amounts of money on the military that we now have. And it would be good for us in terms of being more loved in the world instead of feared or even hated.

Helena Cobban (13:56):

Well, you know, I grew up in Britain, nobody would ever guess that from hearing my voice. And I grew up at a time of decolonization there. And when I was there in the fifties and sixties, you know, every week practically, it seemed as if, you know, you'd have grainy black and white footage of you know, the British governor general in some country in Africa or Asia there with standing next to somebody who maybe two weeks ago had been in jail as a terrorist.

And they would haul down the Union Jack, and they would haul up, you know, the, the flag of independence, of Kenya, or Ghana or Malaya or whatever, and there would be salutes, and it just felt really good to be decolonizing. And what the British people got, you know, because prior to then, like the sun never set on the British empire. You know, my father's generation, they were brought up to think, Oh, you know, this is right and natural in much the same way a lot of people in the political elite in this country think it's right and natural for the U.S. to exercise global leadership. And a lot of what's going on in the Democratic Party is like, “how can we restore U.S. global leadership?” and whatever.

So in Britain, we gave up the empire and what we got was the National Health Service. Like what a great deal, what a fantastic deal. I wish everybody could do that. And especially in this country.

Medea Benjamin (15:34):

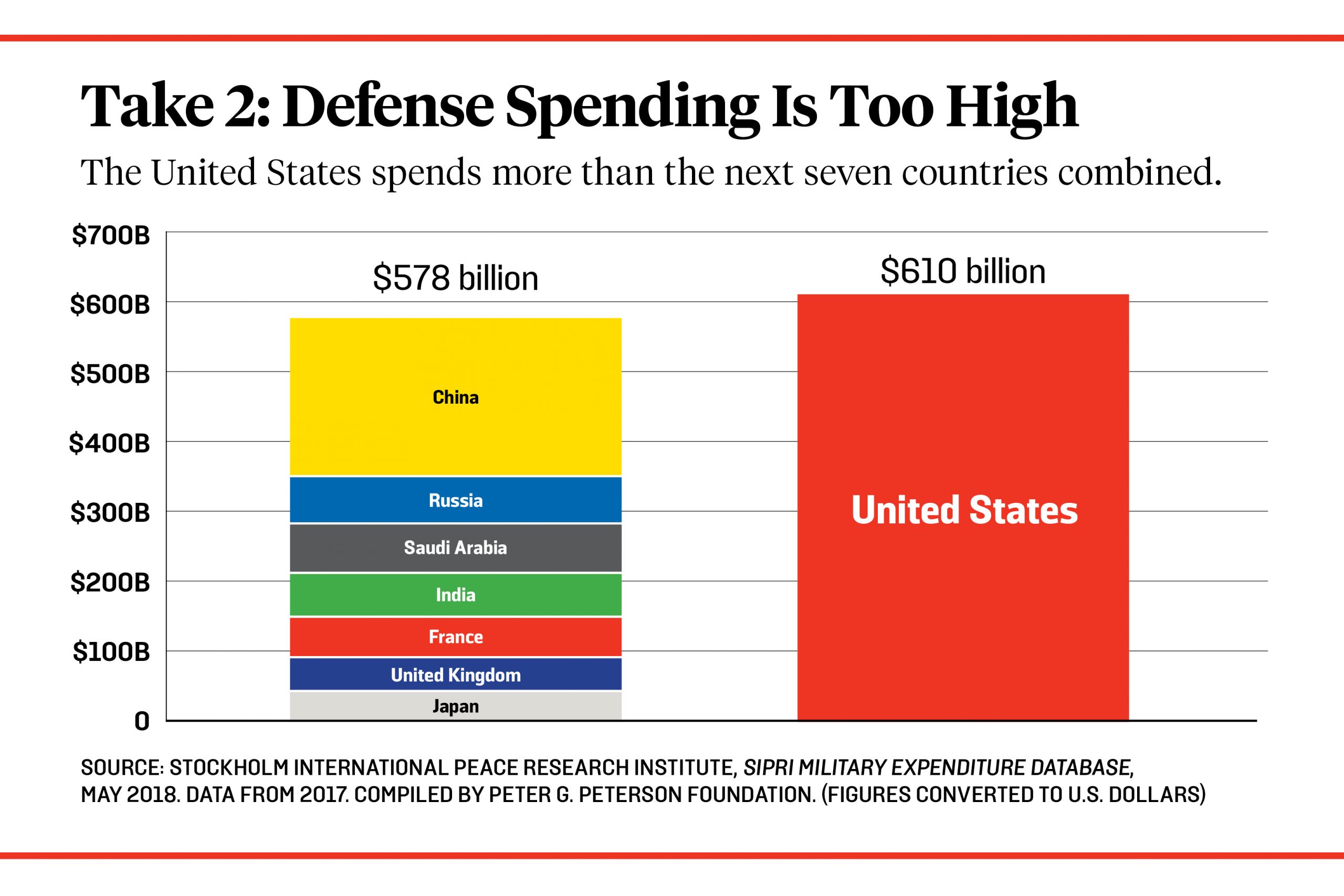

Absolutely. Yeah. And it brings up the issue of how do you spend your resources as a nation. And when we have a country that spends a 54% of our discretionary funds on the military, keeping this empire going for the sake of weapons manufacturers, big oil, the 1% elite, certainly there could be a massive shift in the way that we spend our money. And I'm very excited, Helena, because I think as a result of this pandemic, and as a result of the call for defunding the police, there is an opening that we haven't had in a long time to talk about defunding the military. And this is not just talk among the base now. There is actually a bill that was just introduced into Congress by three wonderful women, Barbara Lee, Pramila Jayapal, and AOC, that put a figure on this and said, we're not just talking about tweaking around the edges.

We're talking about significant shift in funds that we could save up to $350 billion. That's almost half of what we spend on the military now, and be safer and invest that in needs for our community. And I think it's a great time for us to be lifting that up, to be really talking about what could we get out of not dominating the world. If we could stop the wars that we've been in for almost 20 years.

Now, if we could close these military bases, if we could stop the production of weapons we don't need, including new nuclear weapons. What a marvelous thing for the world, and what an incredible thing for us to be then having hundreds of billions of dollars to put into things like a Green New Deal, a national healthcare system, funds for young people to be able to go to college without debt. That kind of reimagining of how we spend our money as a nation is what we need to do right now.

Helena Cobban (17:50):

So I was just sharing for the attendees, a couple of resources that we have. One is the Poor People's Moral Budget, which builds on the work of Lindsey Koshgarian, who thinks - I mean, she has a very stable looking plan for reducing $350 billion per year from the military budget. You know, this stuff, as you said, it's not pie in the sky anymore. And at a time -

Medea Benjamin (18:18):

Nicely, her work, and the fact that it was picked up by the Poor People's Campaign, building on Martin Luther King's twin evils of poverty, racism, and militarism, and adding the environment into that - that the Poor People's Campaign has now totally embraced this issue of the desperate need. We have to take money out of the Pentagon and Reverend Barber himself has addressed this in very detailed ways and taken the work of the National Priorities Project.

And now we see the result of that turning into a bill that is introduced. Let's not kid ourselves. It's going to be hard to even get a couple of dozen members of Congress to be supporting this now, but it's something we haven't had in the past. And we can all work right now to really be putting the pressure on our local elected officials.

Helena Cobban (19:17):

You know, one of the things I was looking at recently on my blog is there was a great thing that happened in the mid-1970s. Portugal used to have this massive empire in Africa, and it just collapsed. You know, I think right now that might be what's happening to the United States’ hegemonic empire around the world. Like suddenly it's as though you let the air out of a balloon, like, what was that all about a Portuguese empire in Africa? Give me a break.

Medea Benjamin (19:51):

And Portugal is all the better for it now, as, of course, are the countries that were liberated. I spent time in all of those countries, Mozambique, Angola, Guinea-Bissau, and saw the beautiful struggles for liberation and how there were so many people inside Portugal that were fighting their own fascist dictatorship at the time, that saw that the liberation of the African people was part of their own liberation. And this is what we have to see in the United States - that if we can liberate the rest of the world from the U.S. having its knee on the boot on the neck of so many countries around the world, we will in the process be liberating ourselves.

And it is I think scary for some people to think that there is a movement out there now for a de-dollarization of the global economy, that they don't want the U S to have a stranglehold on global commerce, because the U.S. has used it in such evil ways, the way that is imposed draconian sanctions on Iran, for example, and forced the rest of the world to do so as well. Done the same thing with the tiny country of Cuba saying, we're not going to trade, and we don't want you to trade with Cuba either.

This is not a kind of economic leadership that the world wants to see. And so there is a big move now to get off of the dollar, to find new institutions, new ways of doing trade that don't involve the dollar. And of course, one of the big issues there is China and China being a major force that is an alternative right now to the U.S. in terms of itts imprint on the global economy. But I think we shouldn’t be fearful of the global demilitarization. We shouldn't be fearful about a smaller U.S. footprint in the world. We should see it as part of our own liberation.

Helena Cobban (22:04):

Yeah, definitely an opportunity to do the many, you know, thousands of, of very basic infrastructure projects and community building projects that we have here at home. I mean, you look at our roads, you look at our schools, you look at our hospitals, you look at the dreadful state of education here. Let's look after our own for a while.

Medea Benjamin (22:28):

And participate in the world as well. But in a different way.

Helena Cobban (22:31):

Yes, as a coequal member. So there was something that I just want to underline here that happened at the end of May, which was when five Iranian tankers made it across, I think they went through the Suez canal, through the straits of Gibraltar, and across through the Caribbean to Venezuela to deliver much needed, I forget how many thousands of gallons of oil, maybe millions of gallons of oil that the Venezuelans needed. And neither at the Suez canal, nor at the straits of Gibraltar, not anywhere in the Caribbean, did anybody choose to stop that shipment? Which of course is very different from what happened last fall when the Iranians were trying to send a shipment to Syria, and it was interdicted at the straits of Gibraltar, I think the world is changing.

Medea Benjamin (23:31):

Well. Yes. And, and let's remember that Donald Trump said at the time that he was going to take stern measures if Iran was trying to help Venezuela. And of course, Venezuela, an oil producing country, has not been able to get the parts that they need, the components they need, to get their oil production back up and running. And they have traditionally exported the crude and imported the gasoline. So despite the threats of the Trump administration they did not do anything about that, which is a huge victory in the sense that the U S now cannot totally control the global trade, but it is a very minor thing in the larger picture. You still have Iran that's so isolated from global trade because of the U.S. you have Venezuela, where the people are really suffering with this economic squeeze, and there is no reason that Iran and Venezuela should really be needing each other, except that they're the only ones that can afford right now to deal with each other, because they're already so sanctioned by the U.S.

So it is a sorry state that the U S does have so much influence in the world. But it is a sign of the U.S. weakening that it can't control everything, especially when it is consumed here at home in trying to put down a pandemic, and an uprising here, and a very dangerous presidential election we have coming up, that people are very worried about how free and fair our own electoral system will be.

Helena Cobban (25:29):

Well, that's true. Yes, I just want to give you the opportunity that since we've been talking about medical things and been talking a little bit about U.S. sanctions to tell us about the new initiative you have to nominate Cuban doctors for the Nobel Peace Prize. So I actually have an image, so why don't you start talking? And I will put this up on the screen.

Medea Benjamin (25:53):

Well, Helena, and this is an incredibly important campaign because it highlights what a small resource-poor country like Cuba of only 11 million people suffering from about 60 years of U.S. economic blockade is able to do, when you have the political will, the kind of moral authority to be putting the island's resources into helping the world. And this is something that Cuba has been doing for a long time. When I was a young woman working for the United Nations in some of the most remote areas of Africa in the late 1970s, I came across Cuban doctors wherever I went, and they were just so beautiful in terms of how they cared so much for the local people.

They lived very modestly. They earned almost no money. They were doing it because they felt that it was important to give back to humanity. And so this program has been going on for decades where over hundreds of thousands of Cubans have been trained as doctors and sent to work overseas.

And over the years, it has become an actual source of income for Cuba, from countries that can afford to pay for it. For example, Qatar and some of the Arab countries actually import Cuban doctors. And a lot of the salary goes back to Cuba, to the government to pay for its healthcare system. It's a win-win situation, except that the U.S. government has actually called it a form of human trafficking because the doctors don't get their full salaries. In any case on top of that regular healthcare internationalism, Cuba has a special brigade made up of a couple of thousand doctors that goes out when there are earthquakes, hurricanes, pandemics, to be the first responders. And they actually started in 2005 to help in the victims of Hurricane Katrina in the United States, with the brigade, Henry Reeve brigade, named after a U.S. person who went to help Cuba during its fight of independence.

Well, the Bush administration wouldn't let the Cuban doctors in. So instead they went to Pakistan after the earthquake there, to Guatemala after a hurricane. And then the last 15 years they've been going all over the world, including in Haiti, after the horrendous earthquake in 2010, staying on to help people in the cholera epidemic that ensued there, and then going to West Africa during the Ebola outbreak, and being the largest foreign contingent to go into the unknown at that moment and say, we will put our lives at risk to try to stop the spread of this terrible disease.

Now we are in the time of coronavirus and they are in 27 different countries, Helena, really doing selfless work, putting their lives at risk. And that's why we think the world should pay attention, should know what the Cubans are doing, and they should be given the largest global prize for peace, which is the Nobel Peace Prize.

Helena Cobban (29:39)

Well, I think that's just a great initiative. So before we finish our little bilateral here, Medea, I I'd like to ask your thoughts on how we prevent this new cold war thing, whatever people are talking about with China, you know, which is seen as the upcoming, very scary power. And you can see this mobilization going on in a lot of the media, you know, a lot of very scary scaremongering type things, even in the media that we would hope would be more calm and less militaristic about it.

How do we counter that? And what do we put as an alternative to having a new cold war with China?

Medea Benjamin (30:24):

Well, let's remember that both the Republicans and the Democrats are now playing right into it. One of Joe Biden's first commercials was how he was more anti -China than Donald Trump was. And so we can't look to the mainstream political parties, but Helena, you and I just had a discussion about this opening to dramatically reduce the Pentagon budget. Well, those forces like the merchants of death, the contractors, the weapons manufacturers know very well, that this is a time when the American people are reexamining what national security means and recognize that spending 20 years in Afghanistan is not helping our national security, that we would be better served by putting that money into stopping this pandemic and the next ones.

And so they are busy at work manufacturing this crisis with China and trying to build up the American fear factor so that they could justify keeping up this enormous Pentagon budget, saying that we now have to prepare for what they call the great power confrontation, no more piddling around with the conflicts in the Middle East, bring the troops out of Africa right now.

They're just bringing troops out of Germany and preparing for this great confrontation with China, which would be absolutely horrific, tremendously costly in all kinds of ways. And you're right Helena. We've got to start countering this right now, to start saying that we need cooperation with China. The entire world is cooperating. We need to cooperate along with them. We need to see China as our allies. Certainly right now, when we were trying to stop this global pandemic there is no time to be throwing around blame on where it came from. Certainly research is needed and investigation is needed, because we need to stop the next one. But what we need to do right now is cooperate in the medical field in all kinds of ways. I mean, we are waiting for a vaccine to be discovered. As soon as that vaccine is discovered, it has to be made available globally.

So there can't be patents. It has to be made available of free for people. Otherwise it won't help any of us. And that's just one example of the kind of things that we need to work with the Chinese on. So it's up to us as people who want to see an end to war in general, and want to see the U.S. have a different role in the in the global sphere to really be aware that a confrontation with China is in the works and that we have to do everything we can to stop it. And particularly right now, stop the narrative and make the narrative be that China is not our enemy.

Helena Cobban (33:41):

Thank you. Yeah, I couldn't agree more with you. And as you said, there's so many things that we need to be doing around the world, everybody in this world community of which we are a member, not a leader. Everybody needs to be working on, you know, we need, we're going to need 15 billion doses of this vaccine, you know, so that means affordable, because everybody needs at least two doses for it to work. And there are so many places around the world that cannot afford the research, cannot afford the production of that. And hunger is starting to emerge in, as a massive problem in so many of those countries around the world. So on that, I think, honestly, I know that the COVID crisis is, is very scary for a lot of people. And I know for the frontline medical workers, it's just like a soul draining, terrible thing. And we see the reports of the medical workers, you know, killing themselves because they just can't deal with it. It is a very scary thing, but it does bring some possibilities to look at the world afresh and to understand as Richard Falk said last week, that we are all vulnerable together, we share that human vulnerability and based on that we can work together.

Medea Benjamin (35:09):

Absolutely. And I think people have been evaluating in a way they haven't before, their own lives: What is important to them, what they want to spend their time doing, what they want to spend their resources doing. I know a lot of young people, including my own children and their friends, re-evaluating: Do they want to still live in the big cities? Do they want to go out to the land? There's a new movement now, afoot all over the world around land reform, around local food production. And this is a time of re-visioning. So there are huge possibilities, but there are also authoritarian figures from Donald Trump to Bolsonaro in Brazil and Orban in Hungary and others who also want to use this moment to bring to the fore, more of the forces of white nationalism and very repressive forces.

So it is a time of great peril, but I also think that the fact that we have the protests we have going on around the world at a time of a pandemic shows, tremendous possibilities. We have just in Seattle alone, a liberated zone in Seattle. I mean, that could spread all over the United States, wanting police-free zones. This call to defund the police, to rethink what community security is about. The call to rethink incarceration is a very expansive call right now that makes people really go deep into these issues around security. And I think the same is true on the international level. So as we've been talking today, I think we have to encourage people, whatever they're rethinking locally, they have to rethink globally as well.

Helena Cobban (37:10):

Well, that's a great segue because we have a number of people queued up to ask questions and many questions. I'm going to bring in our consultant, Charlotte Kates. Hi, Charlotte, you are going to run this for us, so good to have you back with us.

Charlotte Kates (37:31):

Thank you so much. It's great to be back here and to listen to such a fascinating and moving discussion. We do have a number of questions that have been coming in both over the chat and over the Q and A. And I want to start out with a question that we received from Ambassador Peter Ford, who notes that today is when the United States is beginning to force new sanctions on Syria under what is called the Caesar act.

Do you have any comment on these sanctions on Syria and what we can do regarding unilateral measures and sanctions overall?

Medea Benjamin (38:08):

Well as we were talking about before the Trump administration has used these sanctions that have existed previously, it's nothing new. But to an extent that is now covering so many different countries in the world and with this extra territorial nature, not waiting to try to even get the UN to impose sanctions, but doing it unilaterally. And I think the imposition of new sanctions on Syria is a terrible thing. We had a conversation recently with a woman from Iraq, who was talking to us about the sanctions that went back into the 1990s, and they were sanctions that led to the death of hundreds of thousands of Iraqis and transformed the society in many, many negative ways.

And she was saying, these sanctions have lasting impacts that go on for generations. And we were particularly talking about them from a women's perspective, how much these sanctions then have an impact on reducing women's abilities to go out into the workplace, to get jobs themselves, they are the first fired. And how they put tremendous pressure in terms of taking care of families, the inability to get medicines, the kind of structures that are then created to go around the sanctions that are actually fomenting more types of corruption in the society, that then gets blamed on the government that is being sanctioned.

So I think it's a form of economic warfare. It's something that many - the United Nations is speaking out against, the European Union is speaking out against, but they're not doing enough to counter those sanctions. And I think it's very disappointing when you look at the Europeans, of course, now it's very difficult in the face of coronavirus for them to take these measures, but even beforehand, they weren't using their economic power to say, no, we're not going to go along with us sanctions and break the monopoly that the U.S. has had. So yes, these new sanctions on Syria are just another example of why we have to move beyond the U.S. in terms of global leadership.

Charlotte Kates (40:51):

Thank you so much. Speaking, turning again to more on the questions of sanctions and the U.S.’ role in the world. We have another question from Chuck Altman, and that is, what is Venezuela's sin in the view of the U.S. government that merits such antagonism from the United States? I don't see any legitimate reason for these U.S. sanctions or military posturing against Venezuela.

Medea Benjamin (41:17):

A very, very, very good question. One is that the U.S. wants to keep countries, and especially in Latin America, in its sphere of influence. And you have people in the Trump administration who openly talked about Monroe Doctrine 2.0 saying that this policy in the past, which is the opposite of FDR’s good neighbor policy, was that Latin America was the U.S.’ backyard. And the U S would determine who was in charge of Latin America and would make sure that they were favorable to U.S. and U.S. interests. So from the time of Hugo Chavez, coming to power in Latin American in 2002, and forging all kinds of relationships that were the outside the U.S. sphere of influence, even at the time when oil prices were high in Venezuela, and it had a lot of money, creating a new economic trading coalition called ALBA to work outside the U.S. and to help poor countries, even providing subsidized oil here in the United States, in poor communities.

This was something that U S politicians in both parties could not stomach, but there's another reason on top of that. That's important to talk about, especially at election time, and that is Florida. I'm in Florida right now. I see it so starkly, how the policy towards Venezuela and Cuba, and Nicaragua is really based on the exile community that lives around me right here in Miami. There are hundreds of thousands of them. They constitute an important voting block. They're well organized. They have money that they then use to buy politicians in both parties, and Florida is a key swing state. Florida is going to be very important in these next elections. And the Trump administration is trying to create favor with the Venezuelan Americans here by thinking of how many different ways can they show that they want to topple the Venezuelan government.

And for people who haven't been paying attention, in the case of Venezuela, that not only have they put all kinds of sanctions to stop in as well from a trading freely with the rest of the world, but they have also created an alternative government, a fictitious, a fantasy of calling somebody a Juan Guaido, the president of Venezuela, having him have this whole cabinet and ambassadors overseas and pretending as if they are real people with real power, and ignoring the fact that there is a government in power.

And on top of that, putting a bounty on the head of the government of Maduro, Maduro himself, a $15 million for information that would lead to his capture. So it is despicable what the U.S. is doing. The sanctions have been shown to cause the death of tens of thousands of people. And that was before coronavirus. And so the fact that so much of this is being done to create favor and get the votes in Florida makes it even more demonic.

Helena Cobban (44:56):

I think when the Iranian tankers reached Venezuela, somebody said James Monroe was turning in his grave. Indeed. And you look at the effect of everything that you have mentioned, like all the steps taken against the legitimate government of Venezuela, very similar to what has been done against the legitimate government of Syria. Including, well, maybe in Venezuela, they went a little bit further by designating this Juan Guaido as a president, but, you know, in Syria, they created this whole thing called the Free Syrian Army and the Friends of Syria. And they always do this in the name of what they call the international community, but actually you scratch that thing called the international community. And it's always less than half of the governments of the world. And it's all the governments that are kind of, you know, in the slipstream of the U.S. government, but somehow a lot of Americans get this idea that we represent the international community.

Medea Benjamin (46:09):

Well, and the U S has traditionally strong-armed the international community to go along. Let's not forget the coalition of the willing to invade Iraq and what the U.S. did to get that coalition. But also in the case of Venezuela, they use drug trafficking as one of the justifications, but look at where the drugs are coming from. They're coming from neighboring Columbia, which is the ally of the United States. And let's look at what the market is for those drugs.

And that's of course, here in the United States and a country that is a known drug trafficker and in Latin America as a government is Honduras, a very close ally of the United States. So yes, they will constantly look for any kind of justification, including bringing democracy to other countries. And we can look at the consequences of U.S. efforts to “bring democracy” and they are not pretty.

Charlotte Kates (47:12):

And thank you so much. We have another, we have many other questions, but here's another one taking a look at kind of the international scene. Tom Getman asks, what, how do you, what is your vision on Israel and Palestine, the upcoming threat of annexation and apartheid. How do you view this situation? And Newland Smith chimes in and asks, what is the possibility of reducing U.S. military aid to Israel?

Medea Benjamin (47:40):

Good question. And I'm sure Helena, you are much more qualified to speak on this, except I would like to say that the Democrats and Republicans, and both been horrendous on their policies towards Israel, let's remember that the huge amount of money to Israel that is now three point $8 billion a year, going to the military and supporting our weapons manufacturers here was negotiated under the Obama administration. And then we have the Trump administration getting even worse in terms of moving the embassy to Jerusalem, in terms of giving carte blanche now to this annexation, not even pretending that their “peace plan” was a real peace plan.

And Tom, who asked this question, has been involved with us in getting now we have over 75 organizations - so thank you, Tom - including a lot of faith based groups to do a letter to Biden and end Trump on what a real positive just policy towards Israel and Palestine would look like. And we are presenting that to the advisers of Biden and demanding to have a meeting on that. And Helena has helped us with that as well. And I think the answer in terms of would there be any better policy, is would there be a bigger movement in the United States supporting the Palestinians. And we have seen in recent years changing attitudes of the American public and changing attitudes, particularly in the Jewish American community towards Israel, but we haven't yet seen that change reflected in the Congress and certainly in the White House.

But one positive thing I want to point out is how the Bernie Sanders campaign did open things up. Bernie made it okay to talk about Palestinian rights. Bernie made it okay not to attend the gathering, the yearly gathering of the pro Israel lobby group AIPAC. And so I think Bernie did help us open the process up, because he made it possible for these things to be talked about by people who are the contenders for national office in the United States. And that is important.

Helena Cobban (50:20):

Yeah. I guess I would just add to that, that, you know, historically since the early sixties, Washington has been the main supporter/defender of Israel in the international community, well, in the United Nations. And as Washington's power deflates, and I see this as happening fairly rapidly, that will become less and less of a factor that is able to defend Israel's militarism, expansionism, settler colonialism, and so on.

Which is not to say that it's all good news for Palestinians and Syrians and other people whose lands have been taken by, by Israel, because as Israel senses that its international position is getting weakened, it may well lash out. And it has been attacking Syria a lot. And it's continuing obviously the settler colonial project in Palestine. So it's a time of risk for all the people there, especially, I mean, in Syria and in Palestine. People are suffering from the coronavirus in Syria. It's terrible - and so they have that and, you know, nearly twice a week or whatever, Israeli air raids.

So it's, it's tough times for them. And I'm just delighted to see on the streets here in Washington, D.C. - I mean, Medea thinks she's in the belly of the beast, there in Miami - I'm really in the belly of the beast here in Washington, D.C,, but yeah, you're in the belly of another beast. But you know, we see the Palestinians on the streets with their Black Lives Matter flags. We see Black Lives Matter activists with Palestinian flags, and there is like a really wonderful intersectional thing that has been built up since Ferguson, you know.

Medea Benjamin (52:23):

That's right. It was a beautiful intersectionality and black lives matter, got a lot of backlash, even from the liberal community when they put into their movement manifesto, the support of the Palestinian people. But it's been a very important part of the Black struggle here.

Helena Cobban (52:46):

So I'm afraid we probably don't have time for any more questions, which is a pity. We need to carry on the conversation because I think it's just been wonderful to have you with us Medea and all the people that I'm seeing in the chat names that I know, names that I don't know, it's great that people are so engaged here. So moving right along here. I want to get us stopped within the next couple of minutes, because I realize that a lot of people have a kind of a whole schedule of webinars that they go to these days and maybe they need a bathroom break in between, who knows. Just want to tell the people attending this webinar, that this is part of a continuing series, and we've already made the video of the first session available on YouTube.

We're building a resource center on our website that will contain all the videos and a lot of related material and the transcripts. And we're really going to make this continuing conversation into a thing that people can build on and use. If you go to our website, www.justworldeducational.org, you'll see our Syria resource center that we put together there in March and April.

We're going to do something similar for this current webinar series, but of course all this takes resources. So if anybody who's watching this would like to support us, go to our website and hit the donate button and empty your pockets as much as you can. I know these are hard times for a lot of people, but it will really help us get this conversation out there and continuing in a really good way.

Another thing I just want to remind you as you leave, you will be sent to our evaluation. And we really value what you tell us about how these webinars are going. This is a very open-ended series. It can go in any one of a number of directions, and really we appreciate people giving us their ideas and their feedback. We do have two great additional conversations lined up, and I'm about to share the screen - I'm getting a little better at screen-sharing. Here we go.

Next week, Bill Fletcher, Jr. And the week after that, Vijay Prashad. So you can learn more about these fabulous scholar activists if you go to that URL, https://bit.ly/WAC-info. So now really what is left to me is to thank Medea Benjamin. It has been such a blast having this conversation with you, Medea. I love your ideas. I love what you do. You are the epitome of a scholar-activist.

Medea Benjamin (55:49):

Well I've enjoyed it as well. I didn't get a chance to talk about our Divest from the War Machine program. So if people want to know more about that, they can go to the codepink.org website, because we have a whole campaign of how you can get your church, your city, or university to take its money out of the war machine.

And I also want to compliment you and I feel so honored to be part of this series, because I must say that Richard Falk, Bill Fletcher, and Vijay Prashad are some of my favorite people in the world. They’re such beautiful, wonderful thinkers and terrific human beings. So to be among them is a great honor. And thank you for giving me this chance to spend the hour with you, Helena.

Helena Cobban (56:37):

Really it's our honor, and our pleasure, and thank you everybody who's on this webinar, and we look forward to seeing you next week, Wednesday at 1:00 PM Eastern, to be in the conversation with Bill Fletcher. Thank you, and goodbye.

Medea Benjamin (56:57):

Bye.

Session Resources

Speakers for the Session

Medea Benjamin

Helena Cobban

Support Just World Educational

JWE has a golden opportunity to make a difference in this country...

Stay in touch! Sign up for our newsletter: