After America’s war in Afghanistan: Priorities for the peace movement

Compiled by Helena Cobban, President, Just World Educational

The large-scale military campaign the United States has waged in Afghanistan since late 2001 came to an abrupt and (for Washington) ignominious end in August this year, with the collapse of the puppet “Afghan” forces that the U.S. had poured many billions of taxpayers dollars into building, and the concomitant collapse of the puppet Afghan government. The Taliban forces that had ruled the country prior to 2001 and had been battling the U.S. presence there ever since then seized control of nearly the whole country and set about building a replacement government.

U.S. corporate media have fed Americans for many years with a stream of reports portraying the Taliban as “medieval”, brutal, ignorant, and deeply misogynistic. (Few corporate-media descriptions of its role have been as nuanced as, say, Anand Gopal’s September report in The New Yorker, “The Other Afghan Women”.)

Yes, there are many reasons for concern about the nature of Taliban and their rule, including their treatment of ethno/religious minorities like the Hazara and of women. But the Taliban’s fighters and community organizers won the battle for the “hearts and minds” of a majority of Afghans and decisively defeated the U.S. military and its local allies. They are now the effective ruling force in Afghanistan.

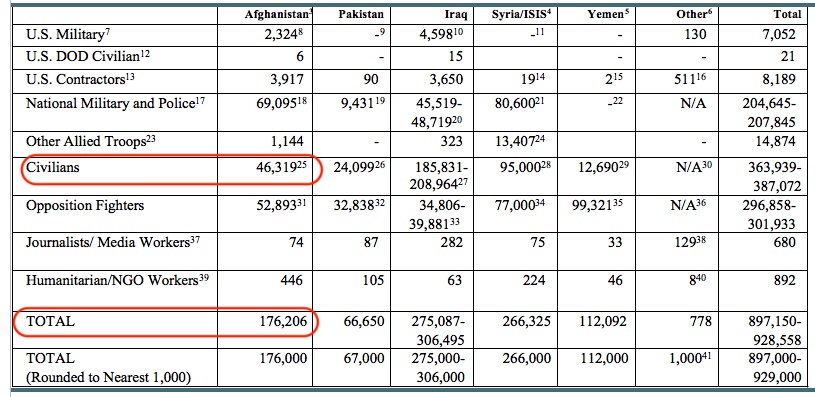

Numerous Afghans throughout the country have expressed relief at the end of the fighting and the end of a brutal, often clumsy U.S. military presence that disrupted many areas of their lives and killed more than 46,000 Afghan noncombatants. But now, the country’s 39 million people face a torrent of massive challenges:

- They face widespread food insecurity and an imminent threat of widespread starvation; the approach of the always-harsh winter; and the need to care for around a million recently returned refugees and far greater numbers of people displaced internally and externally by the preceding decades of war.

- The country’s governance systems at all levels have been pummeled into near-complete dysfunction or non-existence by the deep corruption that flourished under U.S. occupation.

- The U.S. government continues to withhold some nine billion dollars of fiscal aid promised to the country prior to the August collapse, and to withhold formal recognition from the Taliban government.

- Most of the social-action-type projects that American governmental and non-governmental bodies had been pursuing in Afghanistan over the past 20 years, including in the fields of female education and empowerment, have collapsed; and many of their leaders and key activists have fled the country.

This situation, and the responsibility of the U.S. government for so many aspects of it, requires U.S. citizens to reflect deeply on how to respond in a way that best serves the interests of a national population on which our government has inflicted so much harm. These are complex issues. This portal presents briefly annotated lists of resources that can help us think them through, grouped according to these topic-areas:

- Resources on Afghanistan’s humanitarian needs

- Resources on the United States’ historical responsibilities in/for Afghanistan and the geopolitics of the situation (includes some materials on the comparison with the U.S. position in Vietnam.)

- Resources on the situation of women in Afghanistan.

We are hoping to make the design of this resource page stronger and more intuitive– and we can certainly incorporate more resources at that point. So please send along your suggestions and your comments! Thanks, too, to my colleagues in the Peace & Social Concerns Committee of the Friends Meeting of Washington for their contributions to, and support of, this project. ~HC (updated to Oct.29)

After the U.S. war in Afghanistan: Priorities for the peace movement

On October 31st, 2021, Just World Ed co-sponsored “After the U.S. war in Afghanistan: Priorities for the peace movement” with the Friends Meeting of Washington’s Peace & Social Concerns Committee. This hybrid event featured Dr. Zaher Wahab and Graham Fuller and was moderated by JWE President Helena Cobban in a conversation that spanned topics of humanitarian crises, women’s rights, and diplomatic solutions. Both Dr. Zaher Wahab and Graham Fuller hold unique experiences and perspective on Afghanistan and of the United States’ deep engagement with the country. Find the panelists’ full biographies here.

Find the transcript of “After the U.S. war in Afghanistan: Priorities for the peace movement” here.

Resources on Afghanistan’s humanitarian crisis

** The best single source for up-to-date news about the situation in Afghanistan (or any other crisis zone) is the country’s information page on the “Reliefweb” portal. Reliefweb is maintained by the UN’s Office for the coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) and presents updates from the leading, involved agencies of the United Nations, other inter-governmental organizations, national governments, and NGOs.

Via Reliefweb, I accessed this October 7 report from the UN’s World Food Program, WFP, which contained these headlines:

- 14 million people facing acute food insecurity

- 3.2 million children at risk of acute malnutrition

- 8.8 million beneficiaries reached by WFP so far in 2021

- 34 provinces receive WFP food and nutrition assistance

- US$ 200 million required to December 2021; US$ 100 m received

- US$ 300 million required for January-April 2022

Reliefweb also carried this October 13 statement from HNI, a Dutch Health NGO, stating:

The Afghan-Japan Hospital, Kabul’s largest Covid-19 hospital, urgently needs money to pay for generator fuel, food and salaries at the Covid-19 hospital in Kabul. Without it, the hospital will close and people will die… The Afghan-Japan Hospital is usually funded by an international fund managed by the World Bank. These funds are currently frozen as the World Bank cannot send money to a country governed by the new leaders. Much like the World Bank, many donors are unwilling to support Afghan institutions…

And a final mid-October find from Reliefweb was a thoughtful article from the Geneva Centre of Humanitarian Studies, “Negotiation and Afghanistan”, which looks at how experienced inter-governmental and non-governmental aid organizations deal with the challenges of operating in zones controlled by repressive governments or militias.

** In this October 12 article, PBS’s Priyanka Boghani details some of the ways in which the bans on financial flows imposed by the US-dominated World Bank and IMF have been strangling humanitarian actions in Afghanistan.

** Afghan Professor of Education Dr. Zaher Wahab provided an eloquent description of the country’s humanitarian/social crisis in his presentation to this October 14 webinar organized by Solidarity 2020 and Beyond (at 13:30 -> 23:30). Wahab described the country as suffering a “full body cancer” closely connected with the “whole history of colonialism and imperialism”, and spelled out that the United States has been massively destabilizing the country “for 42 years”– that is, since 1979.

** There have been some interesting reports of Chinese aid reaching its neighbor, Afghanistan, in recent weeks. For example, this one from Turkey, this from Pakistan. This report in Newsweek combined news of Chinese aid to Afghanistan with news of Washington’s tight restrictions on much-needed financial flows.

Resources on the United States’ historical responsibilities in/for Afghanistan and the geopolitics of the situation (includes some materials on the comparison with the U.S. position in Vietnam)

** An excellent reflection on the role and responsibility of the United States for the situation in Afghanistan is this October 7 review by Fintan O’Toole of two key books on the topic. O’Toole certainly also adds his own analysis into this review, which appeared in The New York Review of Books. Its very telling title and sub-title are: “The Lie of Nation Building: From the very beginning, the problem with the US involvement in Afghanistan lay essentially in the deficits in American democracy.” O’Toole’s whole essay is well worth reading, as doubtless are also the two books it centrally looks at. If you’re not a subscriber to the NYRB you can still read one free article per month.

(I would add that I believe the problems with the US “involvement” in Afghanistan stemmed fundamentally from the decision Pres. George W. Bush made in September 2001 to launch a military invasion of the the country as a “response” to the events of 9/11. As I wrote at the time in a column for The Christian Science Monitor, there were other much sounder and more productive ways to respond. ~HC)

** Brown University’s Cost of War project presents frequent updates on the human and financial costs of all the U.S.’s wars since September 2001 and, like the Reliefweb portal noted above, is well worth exploring very deeply.

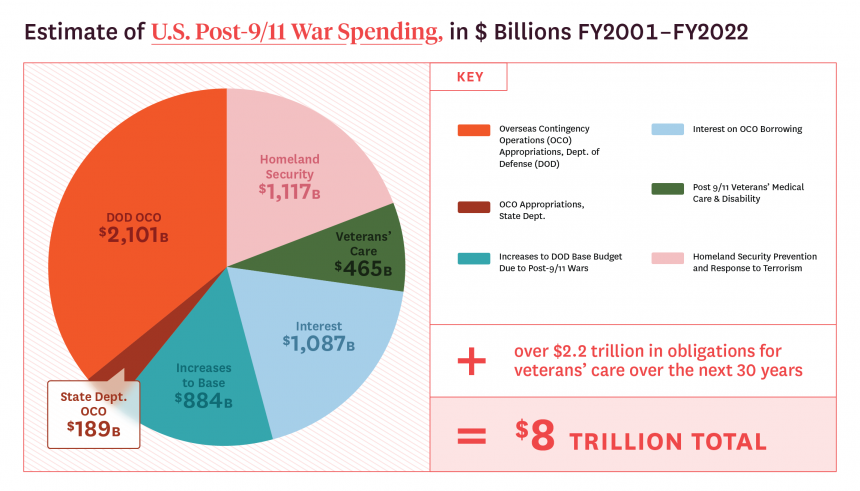

In September 2021, the COWP calculated that all the wars since September 2001 had cost the U.S. taxpayer a total of $8 trillion (see chart at right.) Download the PDF of the full 24-page report here.

On pp.14-15 of the PDF, the COWP estimates “Costs attributed to the Afghanistan/Pakistan War Zone” as totaling $3.4 trillion of this– a little more than they attribute to the “Iraq/Syria War Zone.”

In their page on the Human Costs of War, the COWP presents these costs as follows:

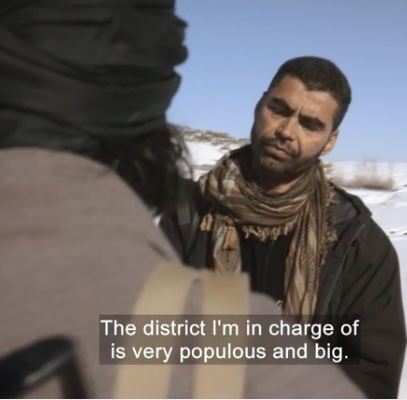

** On October 12, PBS aired a fascinating 55-minute documentary “Taliban Takeover” that presents key excerpts from reporting that their correspondent Najibullah Quraishi conducted in many different parts of the country, from throughout many of the years of war and continuing until after the final U.S. withdrawal. Quraishi also reflects on the significance of some of those interviews.

The interview material and other reporting in the documentary covers times when Quraishi was embedded with U.S. or allied-Afghan troops; reporting from girls’ schools and other civilian venues; reporting he conducted from several parts of the country while he traveled with and interviewed fighters from both the Taliban and the fundamentalist group that emerged as its main competitor, ISIS; and reporting and interviews with leaders and activists in the Afghan women’s movement. It is all well worth watching and provides considerable texture to our understanding of the situation in the country.

** In mid-August, both Graham Fuller, a former CIA station chief in Kabul, and I published short articles questioning the whole record of the United States in Afghanistan. Fuller’s was here and mine was here. In his piece, Fuller wrote:

The ostensible impulse for the American invasion was nominally to destroy the presence of Al-Qaeda in Afghanistan. But the deeper and more profound reason for the American invasion and lengthy occupation was more pointedly to establish a military and geopolitical foothold in Central Asia on the very borders of Russia and China. That ambition was never nakedly articulated but was clearly understood by all regional forces. The “nation-building and humanitarian” aspects of the American occupation were largely window dressing to cover Washington’s geopolitical ambitions. Those ambitions still have not fully died among American neocons and liberal interventionists.

** In early September, Graham Fuller published this very sensible assessment of the geopolitical fallout from the U.S. defeat in Afghanistan. In it, he asked:

[W]ill the United States persist in trying to manipulate this sad nation from afar by aiming at the long-term destabilization of the Taliban regime? Is it better to keep the country in domestic turmoil in order to prevent at all costs a growth of a major Russian and/or Chinese strategic presence there — in their backyard? Are we still hooked on this zero-sum strategic view of the world? The answer is still up in the air. Of course, it depends on how the Taliban run their future government but it will also depend on how an angry Washington chooses to deal with the new Afghanistan.

** Former Marine and international-affairs analyst Douglas Lummis recalled in this recent article that back in September/October 2001 Pres. George W. Bush had refused an offer by the Taliban to negotiate the extradition of Osama Bin Laden. Bush thereby blocked any effort to address the crisis provoked by the 9/11 attacks through diplomatic, juridical, and other non-military means.

Lummis wrote:

Afghanistan’s Taliban government agreed in principle to the detention and extradition of bin Laden, and called for negotiations. But they said that to extradite him they would need to be shown evidence that he was involved in the 9/11 terrorist attack…

Refusing even to attempt negotiating an international dispute is a clear violation of the United Nations Charter Article 33.

** Former U.S. Afghanistan envoy Zalmay Khalilzad on October 27 told the Carnegie Endowment’s Aaron Miller that the U.S. government has to find a way, in conjunction with allies, to deal with the Taliban and to “develop a roadmap” for freeing up some of the billions of dollars of Afghanistan funds still held by the U.S. Watch/listen to their whole 45-minute conversation here.

Parallels with the U.S. defeat in Vietnam

This comparison is not a perfect one. But there are parallels between the U.S. military’s hurried withdrawal from Vietnam in 1975 and its even more hurried withdrawal from Afghanistan in 2021, and it can be productive to reflect on the initiatives the activists in the U.S. peace movement pursued toward Vietnam after that war and those we might consider pursuing in Afghanistan in 2021.

First, let’s note two crucial differences between the situations regarding the U.S. military’s defeats in Vietnam and in Afghanistan today:

- The U.S. peace movement was very much larger, more powerful, and more experienced in 1975 than it is today.

- The Taliban are not the North Vietnamese Communists. (But in the VPCC webinar linked to below, Ben Kiernan argued the Taliban may be more like the Khmer Rouge.)

In mid-September, the U.S. organization the Vietnam Pace Commemoration Committee (VPCC) convened this very informative webinar to discuss the parallels between the Vietnam-era antiwar movement and the U.S. antiwar movement’s tasks and responsibilities toward Afghanistan today. Among the presenters in the webinar were:

- Mennonite peace activist Doug Hostetter, who briefly described his actions undertaken in areas ravaged by the U.S. military in both South Vietnam and, later, Afghanistan.

- NYC-based antiwar activist Laura Jedeed, who recalled aspects of the two deployments she undertook in Afghanistan as a U.S. military intel analyst, and reflected on how the U.S. public had been snookered into supporting the war.

- Australian genocide expert Ben Kiernan, who recalled his time in Cambodia in 1975, when the massive American bombings there had helped incubate the rise of the brutal Khmer Rouge regime, drawing clear parallels with events in Afghanistan.

When considering how Americans today who are concerned about peace and justice worldwide might look at the situation in Afghanistan, it is worth recalling the core principles of the global human-rights movement, including the whole body of social and economic rights, as well as of civil and political rights— and the key right of all peoples to self-determination.

We don’t have to approve of the Taliban in order to see that if the core rights of Afghanistan’s people are to be assured then the major governments of the world, including our own, should start to deal with them. At the very least we need to work to ensure that our government doesn’t inflict additional suffering on the Afghan people through punitive economic instruments like sanctions. But peace activists could also be actively exploring ways to start a range of grassroots, “people-to-people” reparative projects that express our desire to start to repair some of the immense damage our government has inflicted on Afghans.

In the context of post-1975 Vietnam, U.S. peace activists were at the forefront of campaigns to deal with the left-behind landmine problem our military had bequeathed to the country, as well as to investigate and start to heal the many disastrous effects of Agent Orange. What might analogous projects look like, working with Afghan communities today?

Resources on the situation of women (and minorities) in Afghanistan.

The issue of women’s status, rights, and empowerment in Afghanistan and what (if anything) Americans might do about it is a very challenging one for U.S. peace activists to think through. As we do so, we should not forget that women and girls are not the only large social group in Afghanistan that seems to be under some danger under Taliban rule. The situation of ethnic and religious minorities, especially the Shia-majority Hazaras, also seems very precarious– though regarding the Hazaras, they currently (mid-October 2021) seem to be more threatened by the cells of the extremist ISIS organization that remain in many areas and that the Talibs have vowed to suppress.

** CODEPINK’s Medea Benjamin and Ariel Gold argued in this very thoughtful article that feminists should urge the U.S. government to release all funds previously promised to Afghanistan and to lift the sanctions it has imposed on Afghan banks. After noting the severity of the humanitarian crisis faced by Afghanistan’s people they write:

The European Union’s announcement on October 12 of a $1.2 billion aid package is welcome news. So is the announcement by Secretary of State Antony Blinken that the United States would help fund humanitarian aid. But it will be nearly impossible to effectively distribute aid while Afghan banks remain under US and UN sanctions, unable to access physical dollars. And humanitarian aid will not provide salaries for the nation’s civil services.

For that, Afghan’s frozen funds must be released. We understand the opposition to payment mechanisms that flow through Taliban hands. For salaries, the option of direct payments through UN agencies and NGOs is indeed the preferred option, as already existed in the case of many health care workers… And how can the banking system be saved without lifting sanctions? These are issues that the Biden administration and world leaders must solve…

We in the West who call ourselves feminists must grapple with the intricacies and advocate for releasing funds that can stop an entire nation of forty million people from facing a future of starvation and misery.

** I urge anyone trying to think through the matter of women’s rights to spend 40 minutes reading “The Other Afghan Women”, an extraordinary piece of early-September reporting by Anand Gopal, in The New Yorker . The title of the piece itself is telling: a clear nod to the fact that Gopal and his editors realize that most of the information Americans receive about women’s rights in Afghanistan is sourced from that small proportion of Afghan women who are (or were, until recently) living in large cities, regularly interacting in a collegial way with Westerners, and seeking to emulate Western norms regarding women’s role in society. But Gopal used his lengthy experience of reporting from Afghanistan and his commitment to hearing in depth from women living far very far from the big cities, to bring a richly textured and much more complex picture to American readers.

I shall put a few key excerpts from Gopal’s article in below here.

** Another good starting point for thinking through the women-in-Afghanistan issue is this recent resource page, “Which Women’s Rights? Exploring Gender and Peace in Afghanistan”, on the website “Peace Science Digest”.

The page contains two valuable portions:

- First, it summarizes and provides a little reflection on an introguing piece of recently published research: P. Firchow and E. Urwin’s “Not just at home or in the grave: (Mis)understanding women’s rights in Afghanistan” (Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding, 2020.) One key insight the PSD editors take from the article is that, “While there is no denying that Afghan women are subject to severely discriminatory law and practices, war fails to protect women or improve women’s rights… ” The PSD editors also note that, “The imposition of western values and norms related to women’s rights through military force is indicative of colonial feminism, creating a dynamic where Afghans opposed to the U.S. occupation hardened in their opposition to women’s rights—to the detriment of Afghan-led women’s movements (especially outside of Kabul). U.S. occupation reinforced the idea that women’s rights and gender equality are imposed western values, contributing to continued acts of misogyny and violence against women.

- The second half of the PSD page is a Bibliography of very helpful and informative readings on the topic– at the top of which is Anand Gopal’s article!

** On the topic of imperialist feminism, this 2014 article by Deepa Kumar is very thoughtful. She notes, inter alia:

Liberal feminism has routinely viewed women’s participation in the military as positive. In 1991, after the first Gulf war, feminist Naomi Wolf praised US female soldiers for eliciting “respect and even fear” and for taking the struggle for women’s rights forward. What she failed to discuss is the over 200,000 Iraqis, men, women and children, who were killed in that war. US women cannot achieve their liberation on the bodies of the victims of empire any more than Arab women can by raining bombs on Syrians. Empire does not liberate, it subjugates.

** This recent article, “On Afghanistan, Biden must listen to pro-peace feminists” presents a generally helpful and interesting contribution from two leaders of the corporate-ish feminist organization MADRE. They argue for a “feminist foreign policy” that devotes more resources to women’s-rights issues, adding that: “A feminist foreign policy for Afghanistan would demand US accountability for the conditions created by its decades-long military intervention and reparations for the harms generated… ”

These authors argue for some diversion of the funding Washington had previously allocated to the Afghan military to humanitarian aid and support of grassroots movements, including women’s movements, in Afghanistan, and for similar diversion of funds in Iraq or other places where the U.S. has a strong military presence. They also urge Pres. Biden to work harder for a “UN-mediated, inclusive, human rights-based Afghan peace process.” They do not call, however, for an end to U.S. military aggressions overseas.

** Several participants in Solidarity 2020 and Beyond’s October 14 webinar, which was linked to above, made very constructive contributions that furthered our understanding of the present (or recent) state of grassroots organizing inside Afghanistan:

- Jamila Raqib, the Afghan-American head of the Albert Einstein Institution, which works to develop non-violence tactics and education,talked about the rich history of nonviolent organization that emerged in the area of today’s Afghanistan and Pakistan in the 1920s and 1930s, as part of the strongly anti-imperialist struggle of key Gandhi ally Abdul Ghaffar (Badshah) Khan, and about a number of groups inside Afghanistan, including women’s groups, that carry on his legacy.

- The veteran U.S. antiwar activist Kathy Kelly talked about many experiences she has had in recent years, spending time in Afghanistan working with mutual-aid groups in some of the country’s poorest regions. Kelly also talked about the many fact-finding trips she made to Iraq in the 1990s, to Clinton-era sanctions had on the country’s most vulnerable populations.

And now, some key excerpts from Anand Gopal’s article, “The Other Afghan Women”:

Gopal is transparent about the methodology he used in reporting this piece:

This summer, I travelled to rural Afghanistan to meet women who were already living under the Taliban, to listen to what they thought [about current American dilemmas in Afghanistan.] More than seventy per cent of Afghans do not live in cities, and in the past decade the insurgent group had swallowed large swaths of the countryside. Unlike in relatively liberal Kabul, visiting women in these hinterlands is not easy: even without Taliban rule, women traditionally do not speak to unrelated men. Public and private worlds are sharply divided, and when a woman leaves her home she maintains a cocoon of seclusion through the burqa, which predates the Taliban by centuries. Girls essentially disappear into their homes at puberty, emerging only as grandmothers, if ever. It was through grandmothers—finding each by referral, and speaking to many without seeing their faces—that I was able to meet dozens of women, of all ages. Many were living in desert tents or hollowed-out storefronts, like Shakira; when the Taliban came across her family hiding at the market, the fighters advised them and others not to return home until someone could sweep for mines. I first encountered her in a safe house in Helmand. “I’ve never met a foreigner before,” she said shyly. “Well, a foreigner without a gun.”

His description of Shakira, a woman in her forties who had vivid memories of earlier decades of war in her country, dating back to the late 1970s, is beautiful. She lives in a village called Pan Killay, in the Sangin Valley region of Helmand Province.

Gopal gives quotes from three of the women he had talked with in Pan Killay, writing:

In Sangin, whenever I brought up the question of gender, village women reacted with derision. “They are giving rights to Kabul women, and they are killing women here,” Pazaro said. “Is this justice?” Marzia, from Pan Killay, told me, “This is not ‘women’s rights’ when you are killing us, killing our brothers, killing our fathers.” Khalida, from a nearby village, said, “The Americans did not bring us any rights. They just came, fought, killed, and left.”

Later, this:

Entire branches of Shakira’s family tree, from the uncles who used to tell her stories to the cousins who played with her in the caves, vanished. In all, she lost sixteen family members. I wondered if it was the same for other families in Pan Killay. I sampled a dozen households at random in the village, and made similar inquiries in other villages, to insure that Pan Killay was no outlier. For each family, I documented the names of the dead, cross-checking cases with death certificates and eyewitness testimony. On average, I found, each family lost ten to twelve civilians in what locals call the American War.

And this:

Many Helmandis seemed to prefer Taliban rule—including the women I interviewed. It was as if the movement had won only by default, through the abject failures of its opponents. To locals, life under the coalition forces and their Afghan allies was pure hazard; even drinking tea in a sunlit field, or driving to your sister’s wedding, was a potentially deadly gamble. What the Taliban offered over their rivals was a simple bargain: Obey us, and we will not kill you.

And this:

The women in Helmand disagree among themselves about what rights they should have. Some yearn for the old village rules to crumble—they wish to visit the market or to picnic by the canal without sparking innuendo or worse. Others cling to more traditional interpretations… All the women I met in Sangin, though, seemed to agree that their rights, whatever they might entail, cannot flow from the barrel of a gun—and that Afghan communities themselves must improve the conditions of women.

As I say above, however, the whole of his article definitely deserves to be read.

And more, coming soon…

We are hoping to make the design of this resource page a lot stronger and more intuitive– and we can certainly incorporate more resources at that point. So please send along your suggestions!