Exactly forty years ago, in mid-September 1982, the Israeli military and their Lebanese-Falangist allies collaborated in committing a horrific, 42-hour-long massacre in the Palestinian refugee camps of Sabra and Shatila, near the Beirut airport. At the time, I was here in the United States, deep into the writing of my first book, The Palestinian Liberation Organisation: People, Power and Politics, one of the first political studies of the PLO published in English. The book built on interview material and notes I had gathered working as a journalist in Beirut in the years 1974 through 1981.

The news that seeped slowly out of the refugee camps in the days after September 16 was even more heart-stopping for me because during my first year in Beirut I regularly taught a supplementary English class to a group of girls in Shatila camp.

At the time of the massacre, the camps were completely undefended, since the PLO-linked fighters who had previously defended them had all been shipped out of Beirut the previous month, pursuant to an agreement, brokered and guaranteed by the U.S. government, that if they shipped out, the Israeli forces who until August had been besieging the camps and the rest of West Beirut would not advance any further into any of those areas now left undefended.

Actually, I had already spent most of the summer of 1982 in shock. It was in early June that the Israeli forces, under the direction of Defense Minister Ariel Sharon, used a totally contrived pretext to launch a large-scale invasion of Lebanon right up to and beyond Beirut that continued the two months until the August ceasefire, killing many thousands of Palestinians and Lebanese.

But I threw myself ever deeper into my writing work, finishing my manuscript in Spring 1983 even while the situation in Lebanon was still extremely unstable. The book was published in 1984 by Cambridge University Press, and contained a short description of the massacre, based mainly on the reports of its scope provided by my previous colleagues in Lebanon’s Western press corps, and a handful of very brave reporters from Israel.

In the book, I wrote (p.130):

For the PLO leaders, as for Palestinians everywhere, the effect of the Sabra and Shatila massacres was traumatic. They had known what to expect if the Israeli army had been able to enter Beirut; yet all the guarantees they had obtained– including that from the U.S.– that this would not happen had proved worthless.

I also knew, pre-1982, that if armed Falangists were ever allowed to enter the undefended refugee camps, they would be extremely likely to commit massacres. Back in August 1976, I was in the first group of press correspondents that entered the Tel al-Zaatar Palestinian refugee camp in East Beirut when Falangist and allied fighters finally seized control of it after a punishing, weeks-long siege.

Every street within that heavily populated refugee camp had bodies of murdered women, children, and old people huddled along it.

The Falangist military boss at that time, Bashir Genmayyel, prefaced our visit to the camp by telling the journos he was “proud” to be able to show us what we would see there.

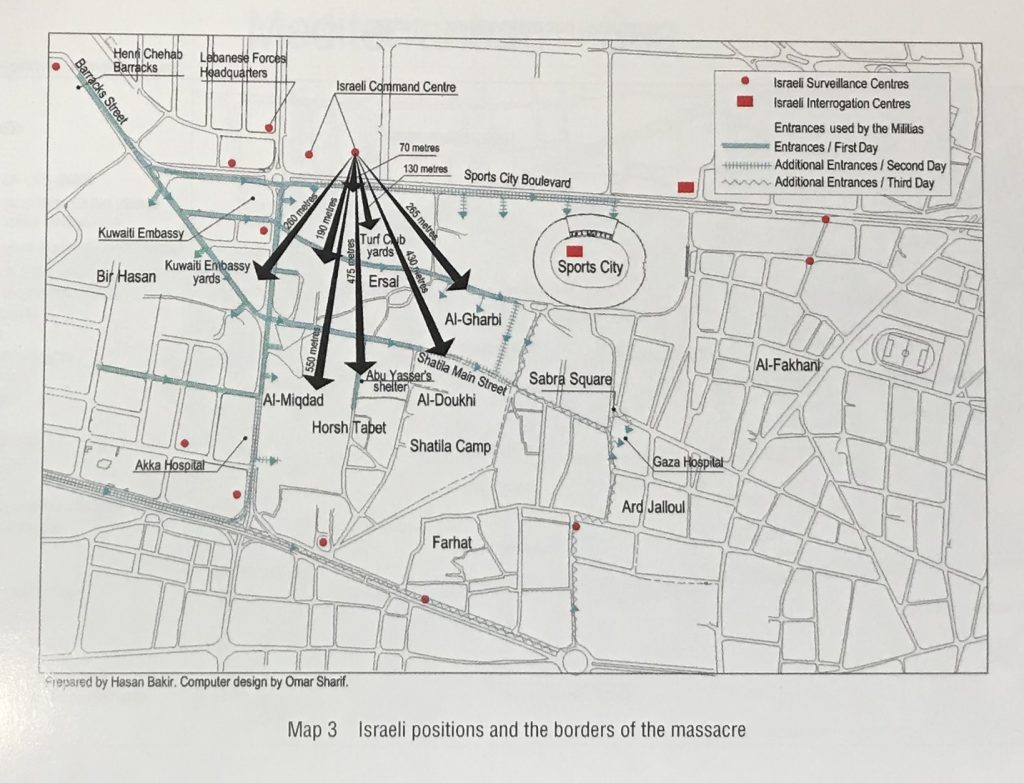

Six years later in late August 1982, Lebanon’s deeply corrupt parliament, acting under the heavy sway of the Israeli forces still encircling Beirut, elected that same Bashir Gemayyel as the country’s next president. But on September 3, before he could be inaugurated, he’d been killed in a large explosion at his headquarters, that killed 23 other Falangist leaders alongside him. Immediately after that killing, the Israeli military started planning an operation in which they would truck scores of heavily armed Falangist fighters to Sabra and Shatila… They launched that operation September 16. For the next 42 hours, the Israeli military maintained a tight security perimeter around the camps and at night-time provided flares, as their contribution to the massacres being committed within the camps by the Falangists.

There is no way that Sharon and his colleagues could have failed to predict the barbarous way the Falangists would behave inside the camps.

As it happens, Gemayyel’s assassination had not been not carried out by a Palestinian. But Sharon was determined to carry out his fiendish plan, regardless of who had killed Gemayyel.

In the summer of 1983, I returned to Beirut. This time, I was completing research for a second book project, a country study of Lebanon that was published in 1985. I was, as you can imagine, very eager to find out what had happened to the group of girls who a few years earlier had been in my Saturday-morning English classes. I talked to my friend the distinguished sociologist and historian Rosemary Sayegh, who had done a lot of work documenting the social history of the refugee Palestinians. “So what’s the best way to get into the camps?” I asked her. “I’d really like to find out what happened to those girls…”

I knew that the security situation inside the camps was tough, as it was throughout all of West Beirut at that time. After the Sabra and Shatila massacres provoked shock worldwide– and an eruption of massive, anti-Sharon demonstrations inside Israel itself— the Reagan administration swiftly strongarmed the Israelis into withdrawing their forces from West Beirut, including the two refugee camps. But the political system in Beirut remained under the strong influence of Israel, whose forces remained a few kilometers south of Beirut. And though Basshir Gemayyel was not now president, his brother Amin had replaced him instead; and the whole Lebanese security apparatus– including those units maintaining control around and within Sabra and Shatila– were under the strong control of the Falangists.

In summer 2983, Rosemary Sayegh’s advice on how I could best get back into Shatila was definitive. “Don’t go!” she said, noting that given the tight Lebanese Deuxieme Bureau/Falangist control of both camps, anyone I visited there would immediately come under suspicion, be detained, or even disappeared. Anguished, I set aside my plan for a visit, but picked up some small shreds of info about a couple of the girls from mutual friends.

In 2002, when I got hold of Bayan Nuwayhed al-Hout’s near-definitive documentation of the massacres, Sabra and Shatila, September 1982 , I found she had written wrote in some detail about the reign of terror that the people still in the camps had been forced to endure during the years after 1982. In November 1982, al-Hout, a Palestinian political science professor and the spouse of the PLO’s long-time “ambassador” to Lebanon, Shafiq al-Hout, launched a broad attempt to try to document the scale and impact of the massacres.

But her work was fraught with difficulties. The Lebanese Civil Defence organization and all the civil-society organizations that had helped in the post-massacre clean-up were so cowed by the authorities that they would not even share with Hout the lists of names of those they had buried. She conducted, and recorded, numerous oral-history interviews with survivors or witnesses to the massacres. But when it came to transcribing those tapes, every typist she approached in West Beirut to do the job turned her down, out of fear of themselves being picked up by the authorities. (Finally, she found someone to transcribe the tapes in longhand. A person writing at home would not attract the attention of nosy or suspicious neighbors to the extent that someone clicking away at a lengthy typing job would have.)

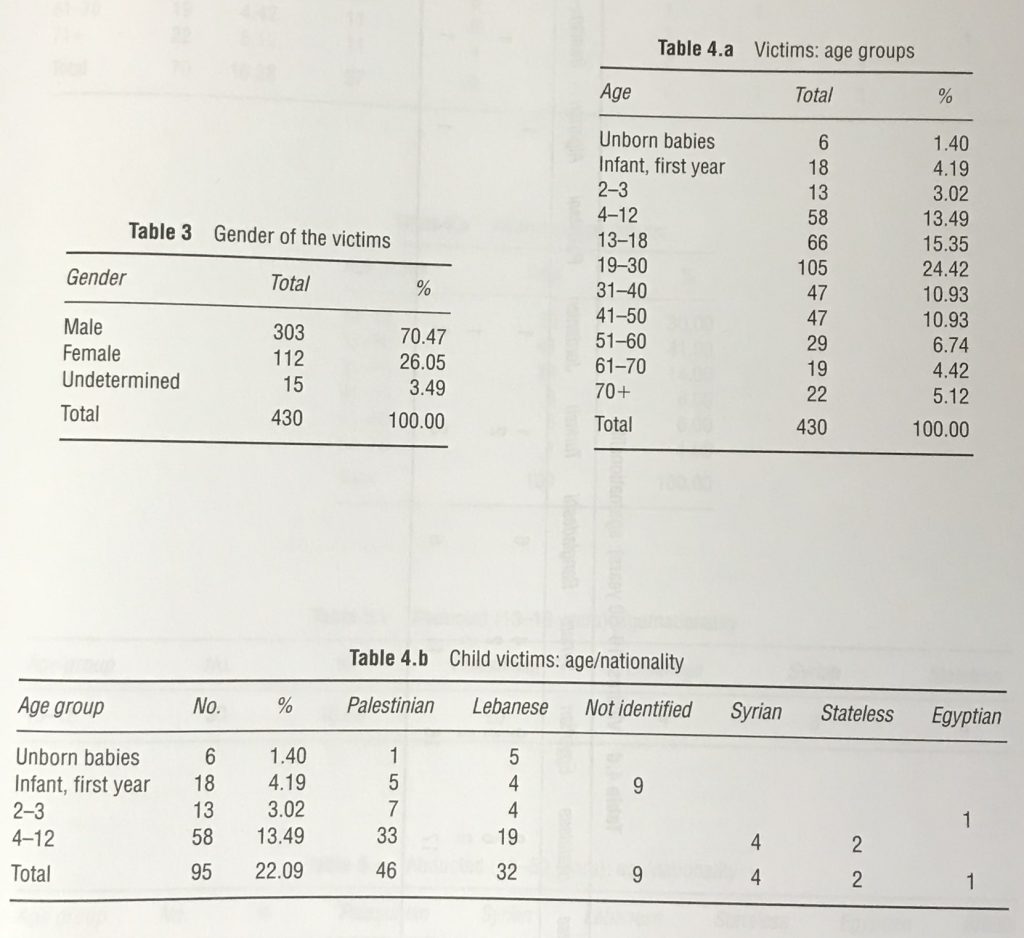

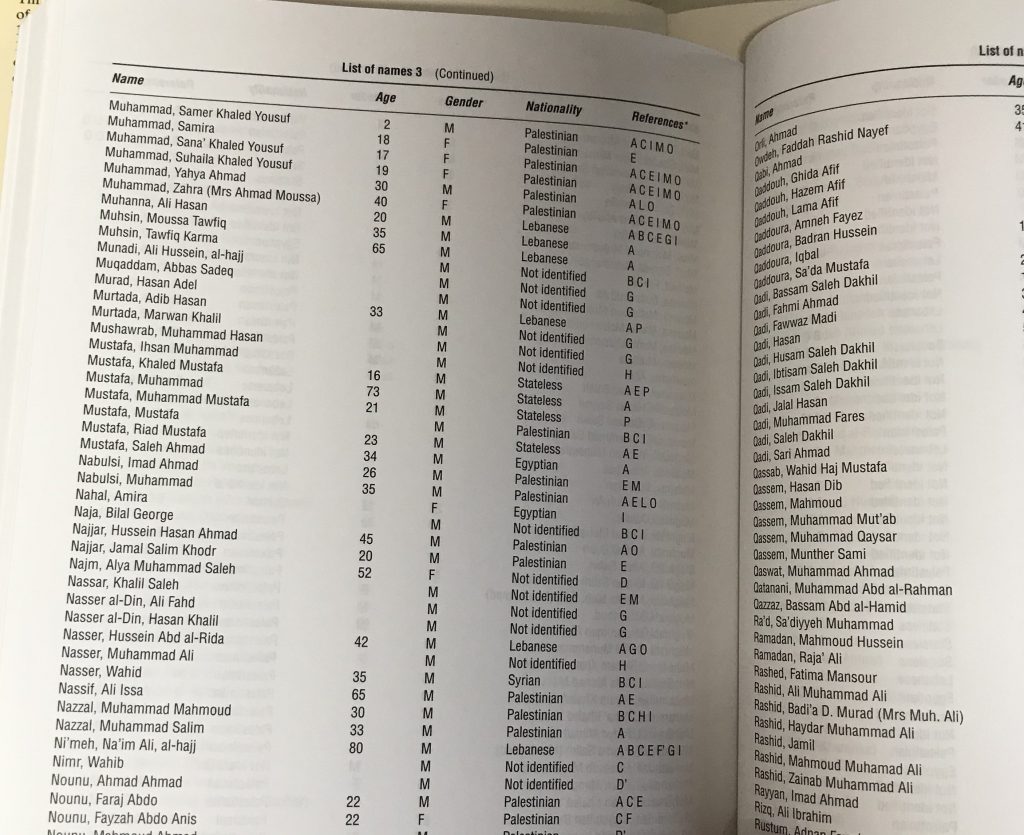

Hout’s work, now published in both Arabic and English, remains the most definitive account of the losses during the massacres. It includes painstakingly compiled lists of names, maps, tables, photos, and oral histories narratives. She was able to document that between those known to have been killed and those missing or known to have been abducted during the massacre, some 1,390 camp residents lost their lives during the massacre, of whom roughly have were Palestinian and the rest deeply impoverished people who were Lebanese or citizens of other countries.

(Click on any image to enlarge.)

I returned briefly to Beirut in 1999 but did not get to spend any real length of time there till 2004. On that visit, one of my first goals was to go back to Shatila. What I found there shocked me more than I had expected.

Some three years after the massacres of 1982, the political balance in Lebanon shifted noticeably: by 1985 the new strong figures in the Lebanese security services were associated the big, politically conservative, Shi-ite militia known as Amal. Amal had long had a fairly strong anti-Palestinian tinge to it. When it gained power in the Lebanese security services it seemed determined to continue the reign of terror the Falangists had been maintained over the camps since 1982. Indeed, it went much further, bringing in Amal fighters from a broad region in an attempt to whittle down the extent of the camps through siege and the force of arms.

From 1985 through 1988, an often fierce “War of the Camps” raged all around the camp perimeters, forcing the camp’s residents into an ever-smaller footprint. After 1988, the rise within the Shi-ite community and the whole of Lebanon of the more militant (and more pro-Palestinian) Hizbullah eased the pressure on the camp residents some. But when I got back to Shatila in 2004, the situation there was still deeply shocking.

I described what I saw when I visited Shatila in November 2004 in these two posts (1, 2) on my vintage Just World News blog. (Apologies for the crazy formating there.) Also, in this column, that I wrote that month for the Christian Science Monitor. Here is an excerpt from the second of those blog posts:

Suddenly we were in a place like I’ve never been in before. In this part of the camp, the people were living in concrete buildings rising seven and eight stories high– and separated from each other only by thread-like alleys just wide enough for two people to pass each other sideways. Almost zero sunlight reached down to street level. The buildings went on and on like that, crammed right up against each other, with only the tiny passageways twisting and snaking between them, for hundreds of yards without end. The small courtyards and sun-fed greenery that I remembered from 1974 were nowhere to be seen.

…

Maha led me expertly through the dim alleys. The lack of any means of ventilation meant that the air felt damp and clammy. God knows how it felt inside the massive concrete cages that crowded in all round us.

“How many people live here?” I asked.

“No-one knows exactly. UNRWA says there are 12,000 registered refugees here. But there are also Palestinians here who are not registered refugees, and there are people who not Palestinians at all. Also, some people who are refugees registered here are now living outside. It’s complicated. Probably somewhere between 17,000 and 20,000?”

This towering warren of refugee shelters covers just under one square kilometre, and is described by some European specialists as the most crowded spot anywhere on the earth.

My big thanks, of course, to my friend/contact Maha who had organized this visit. I hope readers might look at both those 2004 blog posts. Here’s how the second one ended:

… I found the whole visit to the camp quite upsetting, I have to say. For lots of reasons. The depressing sight of how the camp residents have been forced to live… And knowing that these circumstances are completely the result of decisions made by political leaders— with most of that responsibility lying with non-Palestinians, but some with Palestinian political leaders, too.

I was upset for other reasons, too. Partly, some guilt at the sense of my own inattention to what had been going on in the camp after I turned my back on the girls I taught there back in 1974.

When I asked Maha about them, she stood in the alley and thought carefully for a while. She seemed to have an amazing memory for everything to do with the history of the camp. “Khadija… Najat… Ruqaya?” she said. “H’mmm. I think maybe all three of them ended up in America.”

I’ll end here with the same plea I made back in 2004: If any of you, dear readers of this blog post, knows anyone who might fit this description– someone with one of those three names; born around 1960 and grew up in Shatila camp– please could you have them get in touch with me? Thanks!