Transcript: World After Covid with

Hans von Sponeck, Richard Falk and Helena Cobban

Webinar recorded on July 29, 2020

Video and Session Transcript

Session Resources

Helena Cobban (00:05):

Hi, everybody. Welcome to this webinar, which is the last in the current series for our “World After COVID” project. The project will, however, be ongoing in the fall, or perhaps even a little during August. All the webinars in this project and a number of the other related materials have been archived and made available to the public at our online resource center, which I urge you to visit. This is the URL you can go to: https://bit.ly/WAC-resources.

You may want to jot down that URL. Anyhow, at the resource center, you can see the lively conversations I held on our rapidly shifting global balance with people like Medea Benjamin, Ambassador Chas Freeman, Vijay Prashad, Richard Falk, and more.

Today's webinar is sort of a combination of this part of the ongoing project. And I'm delighted to have two guests today. We'll be welcoming back Professor Richard Falk and welcoming, for the first time, the distinguished German diplomat and thinker Hans-Christof von Sponeck.

Helena Cobban (01:15):

Richard. It's great to have you back. You have been an inspiration to this whole project.

Richard Falk (01:23):

I'm happy to be with you again, Helena.

Helena Cobban (01:27):

Hans, it is really my pleasure to reconnect with you after so many years and to welcome you to our webinar series.

Hans von Sponeck (01:34):

Thank you so much. I'm glad to be with you .

Helena Cobban (01:37):

Richard Falk, as you viewers may know, is a much-valued member of our board here at Just World Educational. You can find a short version of his resume and also of Hans von Sponeck at our resource center. And my colleague Charlotte Kates is also sharing those resumes in the chat box for today's webinar.

You may want to keep your chat box open as Charlotte will be sharing other useful online resources in the chat box throughout today's webinar. She will be closely monitoring the chat box on Zoom and the comments section on our Facebook page.

Helena Cobban (02:15):

So if you have questions that you want to put to our distinguished guests today, the best way to do that is to type them into the chat box or the comments section on Facebook. So today, in light of the rapid decline in the United States’ global power and influence that we're currently witnessing, we're going to look at some key aspects of the way the world has worked for the past 75 years under designs that Washington put in place back in 1945.

We're going to look at what is changing now and what we should be working towards, broadly speaking, over the years ahead. We'll be looking at issues of UN reform and the need to overhaul and democratize many of the existing global institutions. We realize we won’t resolve any of these issues in the 40 minutes or so that we'll be talking before we open up the space to your questions, but we do hope that what we achieve today will open or reopen these much needed conversations about global governance.

And we hope that come Fall, we can push those conversations ahead considerably more. So now a very easy question for our guests and either one of you can take it first. What is the United Nations good for?

Hans von Sponeck (03:41):

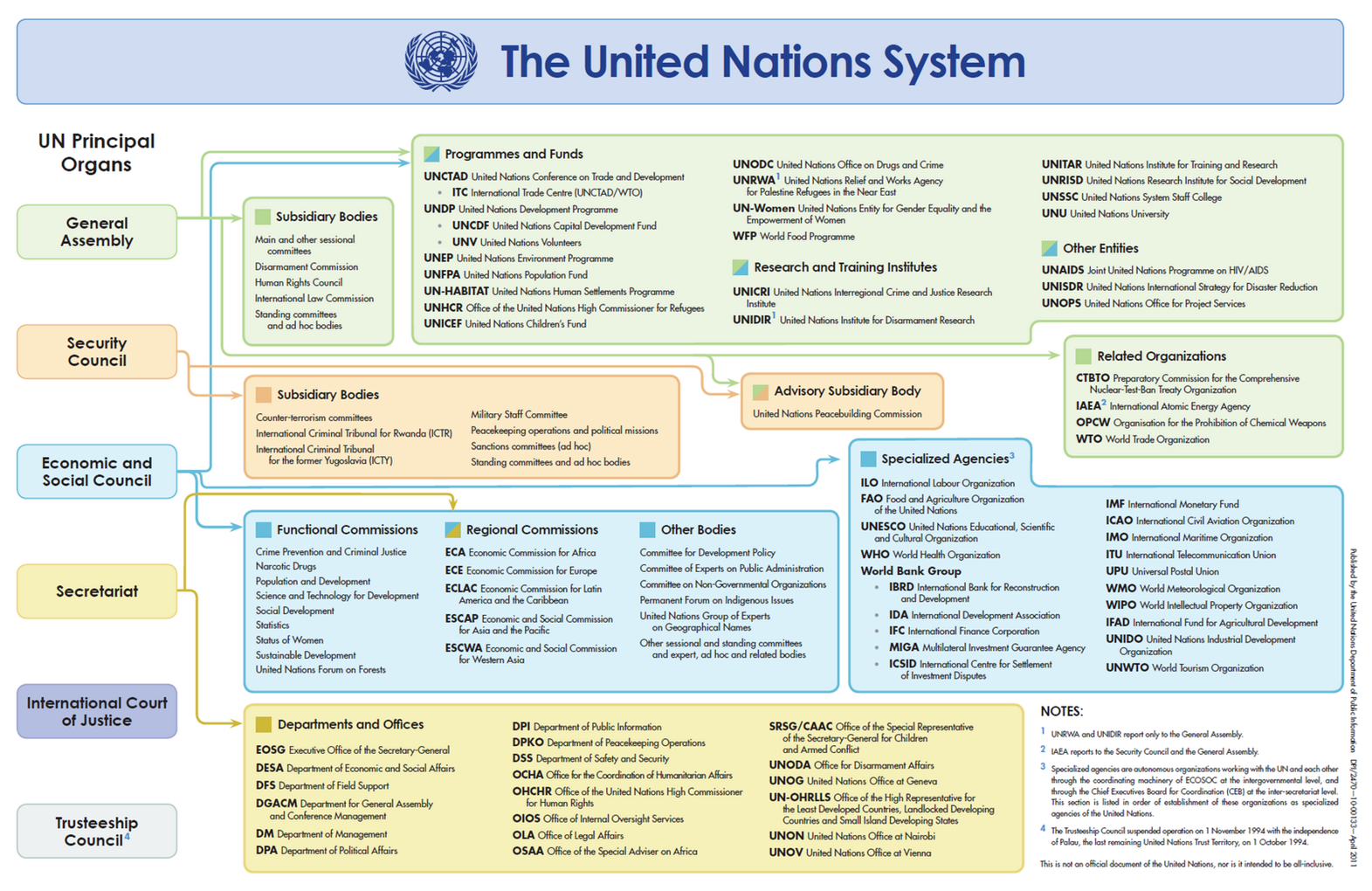

Well, I think there are many, many answers to that, and I often remind people with whom the subject of the UN is discussed that we have to define what UN we are referring to. There is the political UN, most prominently in the news, the Security Council, the General Assembly, but there is this other UN, and that is the UN world of UNICEF, of UNESCO, of UNDP, of WHO, all of these operational agencies.

And to judge the UN you have to be very clear which UN you are referring to. And I obviously want to make a case for the operational UN that is known sometimes much better in Africa, in Latin America and in Asia because it operates in the villages. It operates in outlying areas. It tries to bring health, better education, simply all that which we know about the sustainable development goals that we often discuss.

And then there is another world, I would call it a grim world of difference to the world I just referred to, and that is the Security Council and the General Assembly. And particularly the Security Council, which is according to the UN charter, the body that dictates the policy for the UN as a whole. And I think we need to spend a bit of time to understand that political UN more. Maybe Richard can follow this from what I just outlined.

Richard Falk (05:52):

Yes, I can add a point about the degree to which the political UN, as Hans has depicted it, was always intended to be subordinate to geopolitical maneuvers of the five permanent members of the Security Council that have, by constitutional right, the power of asserting a veto on any decision by the Security Council, which in effect is saying the five most powerful countries in the world – t he five countries that first acquired nuclear weapons - have an exemption from international law and UN obligations whenever they choose to exercise it.

And this was designed into the -- it's not the failure of the UN, it's the failure of the architects that created the UN, who were worried that these big actors, big political actors, would do what they did to the League of Nations, which was created after World War I, and not participate, unless they could keep their discretionary relationship to world politics.

And that's always inhibited the UN of the Charter, which has these idealistic goals and purposes set forth, and sort of secretly ignores this enormous gap in its authority structure.

Helena Cobban (07:46):

Yeah, we actually last week got to hear quite a lot from Marjorie Cohn about impunity and, in particular, the impunity of the United States under the current system. So I urge people, if they didn't see Marjorie's webinar last week, to go and see that. And I also want to just note that our two guests today, Hans von Sponeck and Richard Falk, are currently working on a book on the United Nations system. So we'll wait for the book to come out and have you come back and talk about that.

But in the meantime, my question is -- and maybe I'll send it to you first, Richard, this time -- can the United Nations help with the intertwined current crises of the pandemic, the economic collapse and the crisis of global trust and legitimacy? Where is the United Nations? What can it do?

Richard Falk (08:41):

Well, I think the United Nations in this kind of situation is no better or worse than the behavior of its dominant political actors. And if the United States was behaving properly, as the other four permanent members are, it would be the core of a global cooperative approach to the COVID challenge. And that would make a huge difference both in terms of containing this pandemic, but also in creating a sense that the leadership of the world has the interests of humanity, at least partially is committed to something beyond a narrow and often a greedy sense of national interests. And I would just add one little point about the overall effect of the UN on the world. A Mexican delegate at San Francisco was asked what he thought about the UN -

Helena Cobban (10:02):

At the founding of the United Nations in 1945.

Richard Falk (10:08):

Yes. And he said it holds the mice accountable, but lets the tigers roam free. And that's really the essence of what I think we've been trying to mention. And what Hans said is extremely important because it's -- aside from having the tigers roam free, the operational UN as he described it for most of the countries in the world. And that's something that the public doesn't really understand or appreciate.

Helena Cobban (10:58):

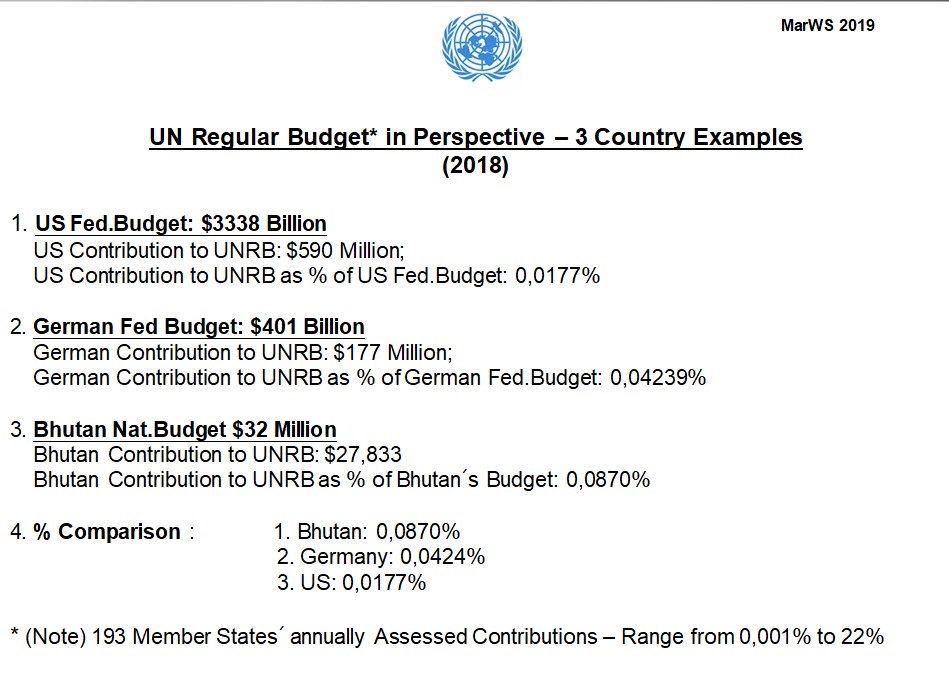

So Hans had actually sent some really handy visuals and I want to share another one that he sent, which you know, here in the United States, a lot of people think that the U.S. is paying way too much of the UN's budget. So here's what Hans had pulled together. And this is done in the European way down there at the bottom where it tells you that Bhutan is paying 0.087 percent of its budget to the UN.

Hans von Sponeck (11:40):

I would just say Helena, the message in that particular graph is the fact that it is not the U.S., it is not Europe, in this case, Germany, that does anything that would allow the word “sacrificing” in financing the United Nations, but it is a small, largely, widely unknown country called Bhutan in the Himalayas of central Asia that, on a per capita basis, pays more than the others - than the industrialized countries. I hope that John Bolton will see that chart because he's the one who kept reminding the world of the immense sacrifices of the U.S. government. I say, U.S. government. I have been a student in America. I know how generous America is, how generous people are in interacting with the outside world.

But Mr. Bolton was so off that it upset me. And this is why I tried to put this chart together to show how minuscule the contribution to this regular budget of the UN is. And let me add one more thing here.

And that is, small it may be, but if you add it all together, what comes out as a total annual budget for the last many years, it hasn't changed. It's 2.6 billion U.S. dollars. Now, take 2.6 - and then I looked at what the budget of the New York police department is. And I found out that the police department of New York City, where the UN is headquartered, is three times the budget that the Secretary-General has available for 193 member countries.

So the peanuts is scheduled by the industrialized countries, particularly the U.S., I must single out here. And it's a peanut budget overall that the Secretary General has to deal with all these multifarious problems that arise every day.

Helena Cobban (14:05):

That’s a great point. And you know, here in the United States, with the Black Lives Matter movement, there's a move to defund the police. Maybe part of the New York City police budget should be sent to the UN instead though.

Hans von Sponeck (14:21):

Good luck.

Helena Cobban (14:26):

More about the UN. We've talked about here on the webinar series in previous sessions, about the growing power of China and the declining power of the United States. And we discussed what's called the Thucydides trap, which is something that was identified by Thucydides, I guess, 2,500 years ago, or whatever, when you have a rising power and a fading power, and the transition isn’t always – well, it can often be very perilous. So, can the United Nations actually help midwife this transition? Maybe we’ll send this back to you first, Hans.

Hans von Sponeck (14:52):

And then I would say the drama is that we are going at this very moment through a trend of polarization. You have a Western world -- by the way, 8% of the global population is West. It's a small, small percentage, and we have a continued demand by one government that the leadership should be unilateral, that there should be exceptionalism in decision making in the chambers of the United Nations. And that is opposed to a very dramatic geopolitical shift towards another part of the world.

So we have on the one side an insistence that the West must play the first violin. And on the other side, you have a very distinct evidence - we can see it every day - of Easternization. And I mean, by that, of course, first and foremost, China, but not only China, there are South Korea, there are other successful Asian nations that are becoming increasingly participatory in political global decision-making. So that points to clash, lots of opportunity for clash. And that means that this whole idea of the overdue need, the urgency of a reformed United Nations, is a very complicated subject to deal with at the moment.

Helena Cobban (16:57):

Richard, what do you think about the ability of the United Nations to midwife this transition?

Richard Falk (17:06):

I think it's not very plausible to expect the UN to do very much, because here you have the two dominant states at the moment, and each of them is very sovereignty oriented. And even without the veto, very unwilling to entrust the vital aspects of its policy to any external political actor. And one thing that's really important is that when we think of a new cold war, we should realize that China is not like the Soviet Union. China has risen to ascendancy through soft power instruments of expansion and growth, and has basically exerted, projected its influence in win-win forms where it builds roads and railroads, and does it other things, whereas the U.S. is continuing to be a militarist, hard-power actor that relies on a network of military bases and navies and every ocean, the militarization of space.

So you have now a tension between two very different forms of power, and it's something new in world history, as far as I know. And the only other thing I would say is there are two points of tension that could produce a terrible escalation toward war. The first is the fact that China now is at the technological frontier. It's no longer just the factory of the world. It's also the source of a technological innovation that used to be one of the American claims to its preeminence.

And the second thing is China is trying to establish its regional authority, which collides with the global state pretensions of the United States. So there are lots of friction in the South China seas and the East Asian waters that could produce the kind of violent incident that quickly might escalate to war. And I see those two arenas as extremely dangerous in this period where, and I've tried to say that it's not really so much a Thucydides trap as a Clausewitz trap, that the real danger is the Western realization that it's in relative decline compared to what Hans referred to in terms of Easternization. And the only instrument that it has to overcome this feeling that it's losing ground to the East is its military power.

And therefore one does have a very frightening geopolitical scenario unfolding at the present time.

Helena Cobban (20:53):

Of course, Clausewitz, the most memorable thing that he said is that war is an extension of politics by other means, which I always under understood to mean that what is actually important is not what happens on a battlefield, it's the political outcome afterwards. And therefore we may now be seeing an era in which this massively bloated military machine that we have been discussing, you know, where you have U.S. bases in 80 or more countries, and you have alliances that lock it into military lockstep or anyway, close coordination, with countries like Saudi Arabia and whatever - all of that may be for nothing. What do you think about that, Hans?

Hans von Sponeck (21:45):

Well, first of all, unfortunately, the year, the number of bases the U.S. maintains abroad is 10 times more. I mean, we are now having about 800 bases that are around the world trying to pursue a very narrow national interest, forgetting that there are another 192 countries.

I would argue and say I agree with Richard, there is a grave danger of confrontation. The West and Europe must try to impress that on its ally in Washington. The West must introduce two words into its political and diplomatic dictionary. One is “compromise” and the other one is “convergence”. If we want to have it our way in and out every year, we will march on that road of confrontation, and the Chinese are much more disciplined, are much better organized. They have the advantage of having a capitalist structure in a communist philosophical, ideological environment.

And that gives them advantages. We have to meet. It's no good that we shun each other. It is no good. And here is a newly researched awareness that I have that I want to just briefly mention.

And that is, I didn't realize that the United States’ voting behavior in the General Assembly, I would classify the U.S. as the “no” nation because the U.S. is continuously and consistently over the years, the one party -- often the only party -- that votes in the General Assembly against something which is reasonable, which has to do with peace. It has to do with social progress. It has to do with development cooperation.

And it is tragic that this country that was so instrumental in creating the United Nations has become an enemy of the United Nations. And if you look at the voting and you see who votes for what, it is very often so clear that that is on the one hand, the South, the developing countries that look to the OECD, the wealthier countries, for help, that vote for something that the operational United Nations is absolutely in agreement with.

And that to do things that bring forward the sustainable development goals and other good things we have identified. And on the other is this desperate attempt. I don't want to sound cynical when I say of a dinosaur that is barely still alive, that kicks and tries to prevent the inevitable.

Helena Cobban (24:50):

So, Hans, I mean, I'm delighted to have you on right now. Let's say you represent all of Europe on our webinar series. No, but there is a serious question about the role of Europe, because for 450 years, it was essentially the gang of white European governments that ruled over and looted from all the rest of the world. And, you know, I grew up in Britain, and Britain was actually a lot more responsible for that than Germany. So, you know, we don't need to go into that perhaps. But then in 1945, Europe got reinvented as a beacon of civilization, uniquely able to reign in the more brash power of the United States. And it was also an inspiration to many in terms of the ability of France and Germany, finally, to get over their rivalries and build something bigger than themselves. But how about now? I mean, Europe is not in a great shape right now, either, you know, from the pandemic point of view, from the economic point of view or the political point of view. What role can Europe play?

Hans von Sponeck (26:01):

Well, the question is, does Europe want to play a role? And the answer is, yes, it does want to play a role, but at the moment, we are very heavily preoccupied with our internal problems. You see, we have right now, if you follow the discussion about a European COVID-19 response to the, the economies, the social systems, of the EU member states, and you could see the confrontation, the conflict within the European Union, you have Hungary, you have Poland, you have Czech, totally different approaches that clash with the Western European Union member countries.

So there are a lot of difficulties that unfortunately chain us right now to an internal dialogue, rather than what we should be doing. Play a bridge maker, a facilitating role between the East -- China in particular - and the West, the U.S. in particular, and our politicians have said, that's a role they would like to play, but they haven't allocated the time to actually do that.

Helena Cobban (27:24):

Interesting. Richard, do you have something to say about the role you see Europe as being able to play?

Richard Falk (27:32):

Well, I would just say -- sort of reflecting back on the prior question, that if in the clash between the Soviet Union and the West, Europe was the central game. The central game was the control -- and after the end of that cold war, Europe lost its geopolitical relevance. The attention shifted initially to the Middle East, and oil and energy, and nuclear proliferation and Israel. And now with this new emergent geopolitical confrontation, Europe is searching, I think, for its own geopolitical identity. And of course, it's searching at a time, as Hans points out very clearly, where it's facing its own regional crisis, a crisis of confidence, a crisis of convergence in his terminology.

And therefore it would take some the emergence of some exceptional leadership in Europe to enable it to do what it could do, which is to play this kind of role. And maybe through the influence it could bring to bear at the UN, maybe change the whole international atmosphere in a more constructive direction. Particularly if we find a way to get rid of Trump and Trumpism in November.

Helena Cobban (29:19):

One thing that we heard from Vijay Prashad earlier in the webinar series, and I think we heard it from a Hilal Elver more recently as well, was the need to actually use the financial heft that the West has in order to do some important things.

Number one, to end punitive sanctions against countries that have been suffering, in the case of Cuba, for what, 70 years now? But in many cases from for many decades. And then to enact major debt forgiveness.

I want to share another chart one actually from a book that I published in 2008, which just shows. This is, as I say, a little bit old because it's from 2008, and it shows the voting power in the World Bank on the inner ring and the IMF on the outer ring in terms of percentage of votes.

So basically from kind of 12 o'clock to 5 o'clock is your rich European countries, Canada and Australia. And then down there around 6 o'clock it's the United States. And then the white portions are Japan, Kuwait, and Saudi Arabia. And then that little portion from like 8 o'clock to 12 o'clock is 150 other countries in the world, you know, so they really don't have much say.

Hans von Sponeck (30:48):

But wait a minute. That is unfortunately, because, mainly the U.S., but the Western group, is absolutely unwilling to change the voting strength of the Bretton Woods institutions. That's the tragedy. You know, Saudi Arabia, other countries that have money, could have easily changed the voting pattern, but if there is a colonial element in the UN system, it's the Bretton Woods institutions, no doubt. You know, that hasn't changed. The U.S. insists 51% of the voting must be in the hands of the Western group. And as long as that is, so the chart that you show, which is a good chart to see, reflects colonialism.

Helena Cobban (31:38):

So maybe it's time to overhaul the system. How, what can we do to do that?

Hans von Sponeck (31:45):

I'm very happy that you asked that question, because I believe that the chances for a reform of the United Nations will come eventually not from the political side, but from civil society. Civil society over the years has shown that it can play an increasingly important role. It isn't there where it should be yet. It should be involved in discussions in the Security Council and the General Assembly. That is happening practically not at all. But the trend, if you ask me, is there a silver lining somewhere? I would say it is with regard to participation of nongovernmental organizations of citizens. Let's not forget the charter starts, “We the peoples.” It doesn't say, “We the governments.” We the peoples. So let us, we the peoples, have a greater share in the dialogue about the future of our planet.

Helena Cobban (32:56):

Richard, do you have anything to add to that?

Richard Falk (33:00):

Well, I think there's a good second distinction. Hans made the distinction between the political UN and operational UN. We also should make a distinction, I think, between the visionary expectations of the preamble to the UN charter and the operational provisions of the UN charter as an international treaty. And they really are two different kinds of documents.

The preamble really looks toward what the UN should be if its ideals of war prevention were given primacy. The constitutional document of the charter really take incorporates a militarist geopolitics into the structure of the UN. And so there's always been a kind of unspoken tension between these two conceptions of what the UN is really about.

Helena Cobban (34:10):

Right. I want to come back also to Hans on the issue of sanctions, because obviously sanctions is something that you have direct and agonizing firsthand experience of, from your role as UN humanitarian coordinator in Iraq in the 1990s, from which you resigned because of your view of the punitive way that the U.S. was pushing that system. What can we do now to end the sanctions that we see against not just Cuba, Venezuela, Syria, Iran, and so many other countries?

Hans von Sponeck (35:02):

It continues to reflect the unilateral decision making of the UN Security Council. There are plenty of proposals. Mr. Kofi Annan talked about, for example, never to use the blunt instrument of comprehensive economic sanctions any longer. Well, smart sanctions was supposed to be the progress Iran shows that there is nothing smart about it, unless you look at it from a narrow American, Washington perspective.

Then it is smart. No, it's not smart. It's, it's unfair. It runs counter to all the human rights discussions and conclusions we have had. I think we will continue to struggle with this deep gap between those, for example, in the General Assembly that want to end the sanctions against Cuba. They want to see our return to the five plus one Iran debate and end the sanctions on Iran.

And yet they are not strong enough to make a difference. The difference is still there where the military power is. And unfortunately, despite what I said about the very small contributions in financial terms to the UN budget, also the financial stick is still strong because the American government pays 22% of the UN budget.

But let me footnote here that this 22% would be higher if America is the only country that is not measured, according to the same key that the others are. Because if they were measured, like the other 192 countries, America would have to pay more than 22%, you know. So there is the power of the money, there's the military power, and there's something else.

Maybe we haven't thought about that enough. And that is the penholder advantage. The fact that you have in the Security Council today, five countries that have from the first day of the existence of the UN until today being party to the debates.

They have an enormous advantage over decision making, because they know every trick there is to have to make, to win the battle, the political battle on the national or regional basis. So the gap between a well-meaning, and I know what I'm saying, well-meaning General Assembly and a hardcore national power-oriented Security Council is there.

And that needs to become victim of a reform debate, which at the moment, unfortunately, is very difficult to have given the overall geopolitical climate that we have.

Helena Cobban (38:18):

Richard, do you have anything to add on this question of sanctions?

Richard Falk (38:24):

I agree with what both of you have said. I think the problem is not only a legal problem of the veto and of the kind of authority that the U.S. has wielded. It's also a failure of an unenlightened foreign policy and world outlook that has dominated Washington ever since the cold war, and it's a bipartisan consensus.

And in this sense, I'm rather pessimistic about what alternatives will come, even if a new leadership under the Democratic Party emerges. If you look at the foreign policy advisors that Biden has selected, they all represent continuations of a militarist geopolitics and a neoliberal approach to globalization. Both of those are death warrants for the world order system we're living in.

Helena Cobban (39:43):

I think that's sadly true, if you look at the people that Biden is currently listening to. Of course, we hope that there is the possibility of building up the progressive movement in this country much stronger than it is already. And it's, you know, we've already seen some new things happening with the Black Lives Matter movement and the degree to which it has gotten wonderful support from, you know, multigenerational groups of people, multi-racial groups of people. The people out on the streets are really quite inspiring in most cases, little bit of violence, but a lot of mass multi-racial activity going on.

And to me, one of the challenges is to try to link these people's struggles for equality and justice and accountability here in the United States, with the struggles of people in the global South, where the need is even greater and the crisis is even more dire. So if either of you has some advice for how we can make these links, that would be really helpful.

Hans von Sponeck (41:07):

I would say that the links, a link comes when people find each other. And people in the U.S., so many well-meaning people whom the world needs, need to find the others. And therefore it is in a way tragic that the World Social Forum, that used to have a prominent role, is now limping.

We need to reinvigorate these global initiatives, support them. The public must show that they see value in this, and that is cross-national. This is global. We need a global cri de coeur of global outcry. Given the situation, we don't need -- it's not about money.

It is about the fact that our, our minds must begin to be linked to our hearts. And we must try and find much greater courage to show the other side, to show the world, in whatever forum there is.

And there are good initiatives. There is, for example, now, a link between individual members of the Security Council and civil society that needs to be intensified and enlarged so that the voices of America join the voices from other parts of the world to try to bring this incredibly powerful and valuable instrument called the United Nations into a situation where it can function as it was meant to function. That's what I would like to see.

Helena Cobban (43:01):

Richard, do you have a thought about how to connect with struggles internationally?

Richard Falk (43:10):

Well, I think there's a need for a movement, a movement internationally and transnationally, that steps outside these formal corridors of authority and power. Because even though, as you pointed out, lots is happening in the streets of America, but I'm not sure it's happening in the halls of Congress or in institutions of America.

And the challenge to establish the link to the global South is, first you have to get some degree of responsible participation by these dominant states in the world system. And that involves what Hans has been saying, not only military self-restraint, but also financial responsibility, ecological responsibility, and diplomatic understanding that we're in this together. And if we don't act cooperatively, and the UN is the best instrument we have for doing that, we face a future that is very bleak.

Helena Cobban (44:34):

I think that's a great note for us to end this portion on Richard, because it takes us right back to the first webinar that you were part of, when you talked about how this pandemic has revealed everybody's shared vulnerability around the world. So that's a good thought for us to now shift to the Q and A portion here. And for this, I'm going to call on my colleague, Charlotte Kates, who will host the Q and A period. Charlotte, over to you.

Charlotte Kates (45:06):

Thank you so much Helena. And thank you to Hans and Richard for a deeply engaged in conversation. Do want to let people know that the video, as well as the transcript of this conversation will be available on the Just World Educational website at the resources page indicated by Helena earlier in the program before this weekend. So, all of the detailed discussion that we've had today will be available for your use in the future.

Now, the first question we have is from Turki al-Faisal, who says the UN security council veto system needs to be reformed. Once a resolution is adopted, implementing it should not be vetoed. As an example, we see UN Security Council resolutions 242 and 338. There has not been a meaningful implementation, in addition to all of the resolutions that have not been passed. And that the power of the U.S. veto is at the core of this problem. What do you think about the veto system in the Security Council and the kind of reforms that may be possible?

Hans von Sponeck (46:12):

Well, I don't know, can I start?

Charlotte Kates (46:16):

Yes, please do. This question is for both of you and your insights would be very much welcome.

Hans von Sponeck (46:22):

I just think that the reform debate is quite advanced for the Security Council. There are, for example, there is a proposal to eliminate the veto.

There is another proposal to have a two thirds majority voting. The misuse of the veto for national per individual country's interests has to stop, through a redefinition of the veto. When can a veto be cast? That's the first step. So that countries don't push their own national envelope, even if the other 14 members of the Security Council think differently.

So there are on the table -- several Secretary Generals have put on the table good proposals for UN reform. What is needed now is the political will to look at these seriously again, and try to take decisions. There hasn't been. It's as if the Security Council is in the icebox right now. There's no decision making capacity at this point, that has to change, We don't have to come up with a fantastically larger range of proposals that are sleeping already for quite a few years in tge Dag Hammarskjold Library in New York, they exist.

So let's unearth them, let's look at them and then have a debate on implementation. And maybe one more sentence, one more word to introduce here, the word accountability. We cannot continue to help an international body like the UN without any accountability. So when a veto is passed, the demand now is increasingly made: You must justify. And number two, the Secretary General has a responsibility to comment on the decision to cast a veto. So there is that a process that hopefully will translate into finally a change in the way the veto is used.

And there's more to it. There is of course the question, but I will not go into, it's not fair to take too much time, but the whole issue of geographical representation in the Security Council. There are two continents that are not represented at all in the Security Council, as far as permanent members are concerned. There is Africa, 54 countries, 1 billion people has not a seat as a permanent member. Latin America has no seat as a permanent member. That all has to change. And when that happens, maybe then it will be a different process altogether when it comes to casting or deciding on a veto.

Richard Falk (49:19):

I would just add a few words that the issue is not imagining how to reform the Security Council, or what are the best procedures of curtailing or ending the veto. It's a matter of how you get the political will in these five countries to overcome their capacity to veto reform proposals. See in other words, there's a sense that this authority that was given to them in the original charter is something that if they relinquish, they weaken their overall international status. And so there's a resistance, at least at the level of government, and often at the level of public opinion, in not weakening a particular permanent member’s voice and leverage within the UN structure. And it really depends on these five countries accepting the discipline of accountability to which Hans referred and how you get that to be done is not an easy question. Given the political consciousness that still prevails in at least Russia, China, and the U.S. and probably to a great extent in the UK and France as well.

Charlotte Kates (51:04):

Thank you very much. The next question that we have is from Martha Schmidt, who is a longterm human rights attorney, and she notes that Article 24 requires the members of the Security Council to act in accord with the UN principles and purposes, which includes respect for international law. She asks isn't the problem, more one of impunity at a domestic failure of the citizenry of the permanent members to demand their governments respect international law, And Hans or Richard, either one of you, would you'd like to take this?

Richard Falk (51:42):

I can say a few words. Yes, it is a complete failure of the citizenry to be mobilized around these issues. And as long as that's the case Article 24 is really a dead letter and the governments and the U.S. government, above all others, it regards its role in the Security Council in the UN as one of pushing its national interests and its geopolitical vision. And it really rejects the notion of accountability to international law as a guiding principle for its behavior. And that's true for Republican leadership. And it's true, unfortunately for Democratic Party leadership, although it's a little bit more disguised when a Democratic president is in the White House.

Helena Cobban (52:57):

I guess I'd like to just jump in here a moment as well, because this is something that I've thought a lot about. You could say that the structure of the veto system right now is, at a global level, a really strong example of white privilege. You know, you've got the United States, Russia, England, and France. So England and France were historical colonial powers. The United States. and to a certain extent are - well, Russia, we can leave aside for now - but the United States is a European settler colonial creation. And Russia is another white European power that engaged in a certain amount of settler colonialism over there in the East. So China is in essence, the only representative of the global South in the veto structure, and we as white Americans, well, I'm a white American, Richard is a white American, Charlotte is, I don't know, are you American or Canadian? You know, we're very aware of the role of white privilege domestically and the need to combat it. Why don't we do that at the global level? That's just a question I put out there.

Hans von Sponeck (54:24):

Well, isn't that what you're saying? An encouragement to make sure that we have a Security Council that reflects more geopolitical reality than is the case at the moment. Africa has to be there. Latin America has to be there. More of Asia has to be in the Security Council. And when you get this balance then you are maybe achieving what you had in mind with talking about this imbalance that exists at the moment with too many white faces sitting in the Security Council. I think if we want a UN that functions there is no other way, but to create this kind of an enlargement. One can talk about how big that should be, but it has that it has to come. If we want a United Nations, a political United Nations, then it's clear that that's the way we have to look at it. You know, the status quo is no longer acceptable and governments and people also, increasingly informed people, will not accept this kind of United Nations decision making process. And it cannot be, it cannot be.

And this is again, part of what I'm researching at the moment that year after year after year, the same resolutions are being passed almost verbatim, and nothing happens because there is one country that obstructs what others want. So broaden the composition, and that's a step in the right direction.

Charlotte Kates (56:18):

Thank you again for these answers in this insightful conversation. I'm just going to it back over now to Just World Educational president Helena Cobban for some concluding thoughts. And I'm sorry for all of the questions we weren't able to address in our limited time available.

Helena Cobban (56:36):

Thank you so much, Charlotte. This has been a really important and thought provoking conversation. I'm particularly sad to bring it to an end because this whole webinar series has been so stimulating, informative and engaging for me to pull together. But this is only the end of this portion of our project, not the whole of the World After COVID project.

So stay tuned for news of our fall plans, and go back to our resource center there. You know, everything that we do here costs money. I'll just leave it at that. We do what we can on a shoestring budget, but we'd love to have your support. If any of you watching today are able to, to donate to Just World Educational, go to our website, www.justworldeducational.org, where you'll find a donate button.

And we really appreciate everybody who has been giving throughout this whole project. First of all, Hans, I want to turn to you and say what a real honor and pleasure it has been to have you on today's webinar.

Hans von Sponeck (57:46):

Thank you very much for saying that. Thank you. Thank you, Helena.

Helena Cobban (57:50):

And now, Richard. So it was, it was Richard who I had several conversations with him back in early June and they inspired and then launched this whole project. So starting off from his earlier webinar appearance, with the recognition that he gave there of the fact of the deep vulnerability that all human beings currently share. So Richard, thank you for launching us. Thank you for being here with us in June and thank you for being with us here today.

Richard Falk (58:24):

It's been my stimulating pleasure. Thank you for arranging and managing it so well.

Helena Cobban (58:33):

So, finally, I want to remind people that we welcome your evaluations of both today's webinar and the whole series. I don't know how many any of you have actually had the chance to take part in. I know some people have been with us for all eight so far, which is great.

So as you leave today's webinar, I hope I've got the thing set up right. You should be sent straight to the to the evaluation form. If you could fill that out, that would really help us going forward. So now I want to thank Charlotte Kates, who has been my comrade in arms in planning all of this. Charlotte, It's been just a pleasure to have you, and of course we are expecting and hoping that you will stick with the project wherever it takes us in the fall.

And now I just want to thank all of you, the attendees at this webinar. Thanks for coming with us on this journey of reflection. Tell your friends about our resource center, send in your suggestions in the evaluations, see you in the fall, and have a great and safe August.

Speakers for the Session

Hans-Christof von Sponeck

Prof. Richard Falk

Helena Cobban

Support Just World Educational

JWE has a golden opportunity to make a difference in this country...

Stay in touch! Sign up for our newsletter: